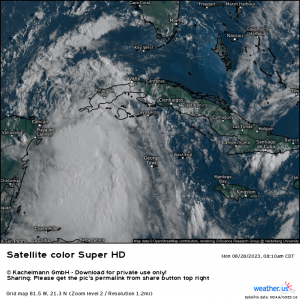

What Will Happen Once The Remnants Of Tropical Storm Amanda Arrive In The Bay Of Campeche Tomorrow?

Hello everyone!

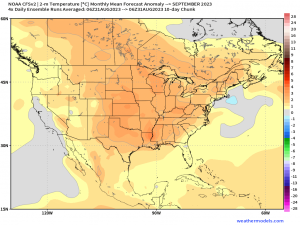

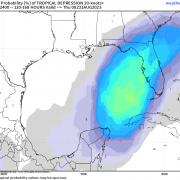

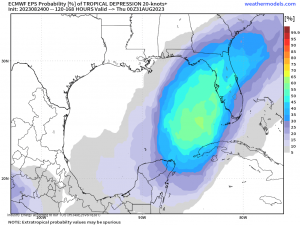

This week, our attention will be focused in the Gulf of Mexico where a tropical disturbance may develop into the season’s first system with the potential to bring substantial impacts to the US coastline. Uncertainty is still quite high regarding the system’s eventual track and intensity, so it’s important not to rush towards any one possible outcome. I’ve advocated both on this blog and on twitter for a “wait and watch” approach. Understandably, this is a bit frustrating for residents along the Gulf Coast who are eager to know whether they need to start preparing for a potentially impactful storm, or if they can (finally) cross something off the “to-worry-about” list.

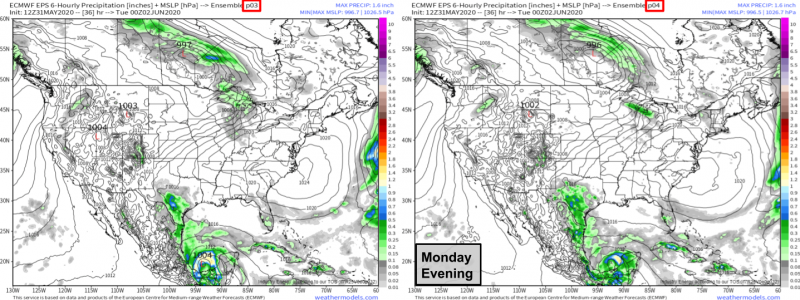

The goal of this post is not to offer any further clarity on the forecast. I provided the clearest analysis I could yesterday afternoon, and if I were to attempt another post with the goal of forecast clarity, it would sound nearly identical to that which I wrote yesterday. So if you’re interested in the forecast, please click over to that post. In this article, I’m going to attempt to show why forecasters like myself are being so vague about the potential outcome of this system. We’re going to follow two EPS ensemble members (number three and number four) as they attempt to forecast this system’s evolution during the period starting tomorrow afternoon and ending on Friday. One of them is going to show a major hurricane landfall in Texas on June 7th, and the other is going to show a weak tropical storm moving onshore in Louisiana on June 9th. See if you can guess which is which before it’s revealed at the end of the post.

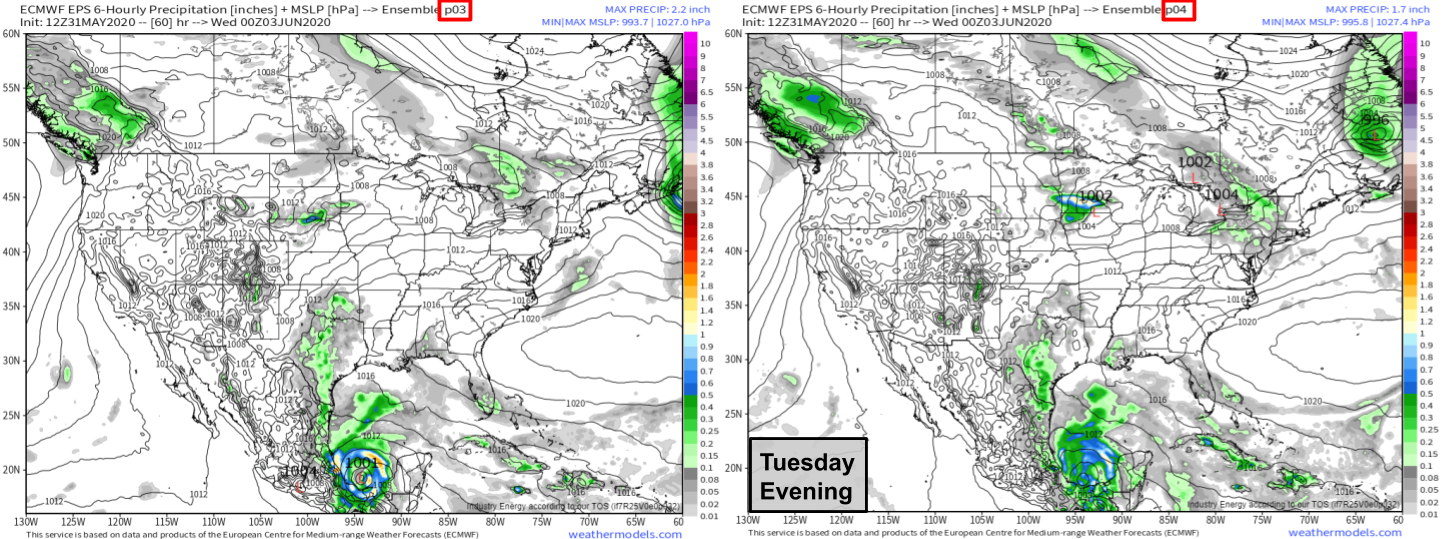

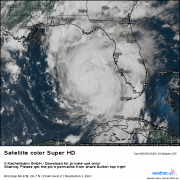

The two forecasts for Monday evening are nearly identical. Both forecasts show a closed area of low pressure somewhere in the Bay of Campeche as the remnants of Tropical Storm Amanda emerge back over water and begin redeveloping. Ensemble member three is a bit stronger with the system, but also shows it developing a bit farther west than ensemble member four. Certainly neither screams “hurricane” at this point, but that’s to be expected since it takes time for tropical systems to develop even in a favorable environment.

By Tuesday evening, the two forecasts are still nearly identical, save for a few thunderstorms that ensemble member three seems to think will be a little stronger than ensemble member four’s forecast. As with Monday evening’s forecast, the plotting algorithm has tagged ensemble member three’s depiction of the storm with a nice “L” and central pressure label while it hasn’t done that for ensemble member four’s forecast. This seems to be nothing more than a quirk of the plotting algorithm. Both forecasts show a low with several closed isobars, indicating that it’s a circulation separate from variations in the environmental flow. Using the much closer inspection of ensemble members available at weather.us, I found that ensemble member four is expecting a minimum pressure of 1004mb at the time of this forecast. That’s a hair higher than ensemble member three, but the difference is almost negligible.

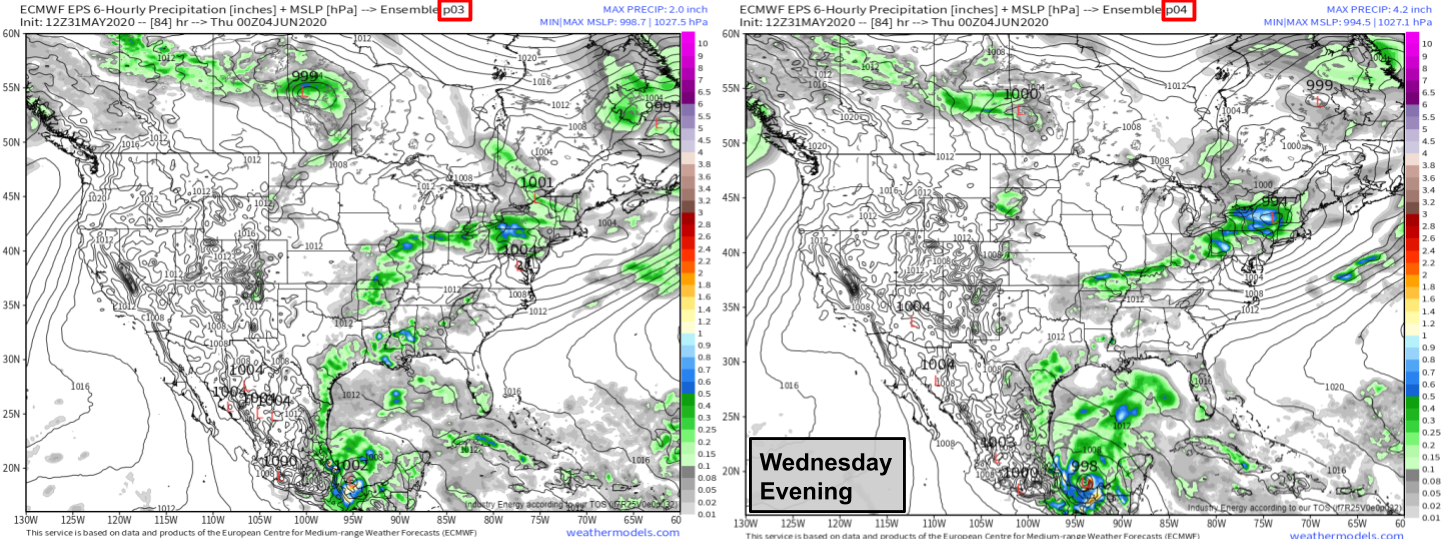

By Wednesday evening, both forecasts show the system drifting south towards the Mexican coastline. By now, ensemble member four’s simulated storm is now stronger than that shown by ensemble member three, though the difference is still a mere 3mb which is nearly trivial. If you squint hard enough, you’ll notice that the center of the system shown by ensemble member four is ever so slightly farther east than the center of the system shown by ensemble member three.

Why is this? I suspect that each ensemble member threw the storm’s center under a different thunderstorm complex when the remnant circulation of Amanda first emerged in the Gulf of Mexico. Remember than in a setup like this where a tropical cyclone is forming from a small circulation embedded within a gyre, the exact center of the cyclone could change drastically depending on exactly which thunderstorm it decides to pop under. A recent example of this issue is Tropical Storm Bertha which only developed into a tropical storm because the center of a loosely-organized tropical disturbance over Florida decided to jump under a cluster of thunderstorms that happened to be offshore over the warm waters of the Gulf Stream. Had the center stayed where it was initially (over land), it’s unlikely that Bertha would’ve ever formed. A similar dynamic is likely to play out here. There will be many “candidate centers” or areas with enhanced vorticity (spinning motion) coupled to thunderstorm complexes. Exactly which one of these candidate centers is “chosen” by the storm to coalesce around will make a huge difference in the storm’s eventual fate. If the “chosen candidate” center drifts onshore, the storm is unlikely to develop much past a mid-grade tropical storm. If the “chosen candidate” center is one that remains offshore, the storm could strengthen into a strong tropical storm or hurricane rather quickly.

The processes relevant to this part of a storm’s development occur on scales too small for our global weather models to see directly. That means they make their best guess, but there’s a lot of room for error. That’s why you haven’t seen me post a single deterministic model forecast (like the operational ECMWF or GFS) for this system. Without knowing how these delicate convective dances will play out, and exactly which thunderstorm cluster the storm will anchor itself to, we don’t know where this storm is going or how strong it will be.

With that in mind, let’s continue watching EPS members three and four try their best to figure out the processes outlined above.

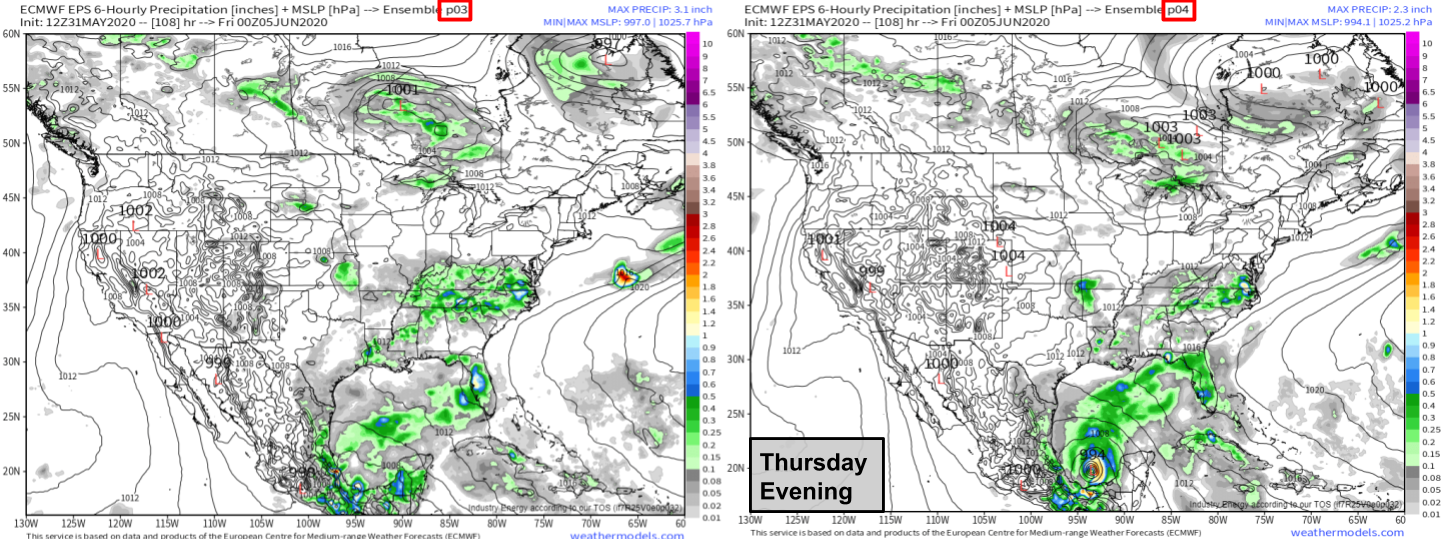

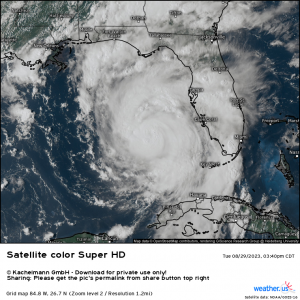

Now it’s pretty clear which forecast is which. Ensemble member three’s simulated storm anchored itself to a thunderstorm cluster that drifted too close to the Mexican coastline and fizzled out. Ensemble member four’s simulated storm organized around a different thunderstorm cluster that managed to stay out over the open ocean. As a result, ensemble member four’s storm quickly intensified into a strong TS by Thursday evening while ensemble member three’s simulated system didn’t reach tropical storm intensity until it moved onshore in Louisiana on June 8th-9th.

If you were responsible for making forecasts based on these ensemble members only using information from Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, could you have matched the proper forecast to the proper ensemble member? There were a few hints, but sometimes they were contradictory. EPS member four kept the storm ever so slightly farther east/northeast throughout its developmental stage. That meant that it had more room to breathe and had a lower chance of meandering onshore. However, it also started off weaker. In my post yesterday, I explained why a storm that was able to develop more quickly might tend to drift north/northeast faster, thus avoiding a sandy grave southeast of Veracruz. However, this analysis showed an example of the exact opposite happening! The ensemble member with the stronger storm initially ended up sending it farther south/west (only by a little) and thus it was unable to develop until much later.

Does that mean my analysis yesterday was wrong? Maybe. But more likely, the storm’s eventual track and intensity is a function of both its initial intensity and its initial position. In other words, a faster-developing storm is more likely to move north, but this influence on the system’s track can be offset if the storm starts off farther southwest.

As I mentioned at the top of this post, no part of this analysis is intended to comment on what will actually happen with this storm. The scenarios shown by ensemble members three and four are both equally plausible in my mind at this time. The NHC seems to agree (to the extent that they are commenting), giving the system a 50% chance of developing into a tropical cyclone by Friday afternoon. What I hope you got out of this discussion is a greater appreciation for how very tiny changes in the system’s behavior over the next 3-4 days will lead to huge consequences for the 5-7 day forecast. This of course is a classic example of the “butterfly effect” where a small perturbation to a chaotic system leads to rapid divergence in outcomes later on. Our best tool in the fight against forecasts busted by chaos is to look at ensembles. For a refresher on what ensembles are, how they work, and why they’re so useful in situations like this, please check out this blog post.

I will have another forecast-oriented blog post tomorrow.

-Jack