The Grip of a Megadrought, Part 2: Lurching Through Disaster

It’s amazing what two months of a persistent atmospheric pattern can do in an environment as fragile as the West’s. In 2017, two months of repetitive, fanning atmospheric river events brought California from expansive drought to a hydrological windfall. In 2020, alternatively, two months of exceptionally dry weather in the heart of the state’s rainy season combined with anomalous heat to usher in the return of sprawling drought.

I detailed the tumultuous recent history of Western US hydrology in my blog post on Saturday, the first installment of a three-part series on the worsening megadrought there. Where I left off, the reservoirs and snowpacks of California had just seen a massive jolt in the form of a January and February of record-challenging heat and warmth. This launched parts of the region back into moderate to severe drought delineation, with the lack of snow pack leading to exceptionally dry soils by the middle of the wet season.

Drought is dangerous. First to mind are concerns about water shortages that threaten livestock and agriculture, and can even force conservation mandates within city limits. But even before reservoirs dry to that extent, parched conditions can threaten population centers significantly. Dry soil is easier for the sun to heat up than wet soil, as less energy needs to be partitioned to evaporate water. When droughts dry the ground out, therefore, they can be accompanied by dramatic heatwaves that push the upper boundaries of climatology and physically stress the vulnerable. Additionally, a combination of this dry soil and resulting hot air with dried organic matter can support the potential for massive conflagrations when favorable wind patterns develop. Both of these fears proved pertinent as the 2020 dry season enveloped the West.

The period of dry weather closely followed a wet 2018-2019 water year, leading to fears that the additional organic matter load from the anomalous recent rain, dried by the more recent drought return, could herald a repeat of the catastrophic 2018 fire season. This was validated dramatically and quickly when, in mid-August 2020, a dramatic multi-day barrage of low-precipitation thunderstorms ignited dozens of simultaneous wildfires. Amidst conditions very favorable for fire spread that included dry air and fuel availability encouraged by drought, the conflagrations quickly enveloped huge swaths of forest, congealing into a number of massive complexes.

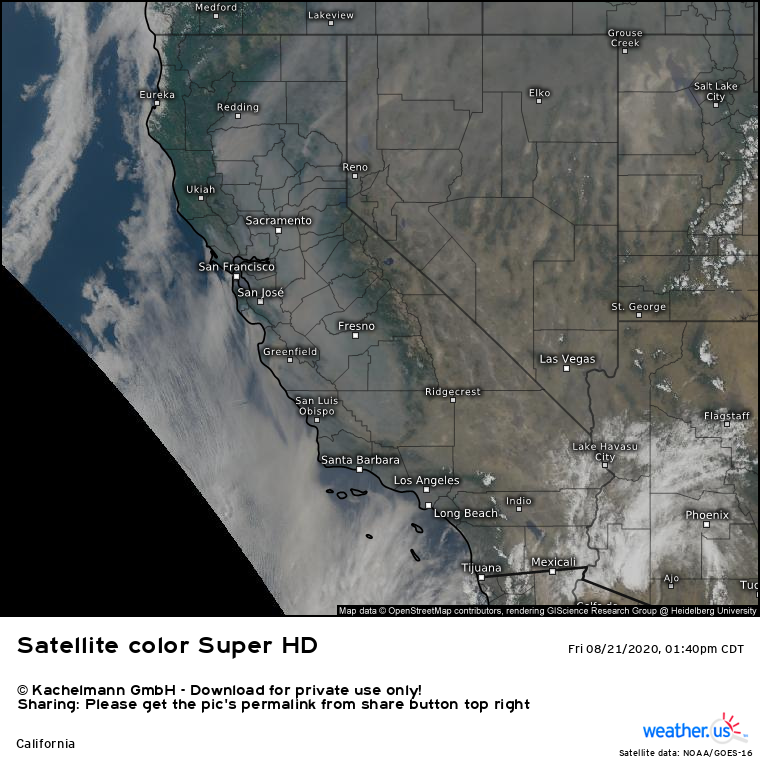

The amount of acreage consumed by these fire complexes was stunning, and the statistics are almost incomprehensible. Four of the five largest California wildfires ever were ignited by that onslaught of lightning, and one even surpassed the massive Mendocino Complex, burning more than double the area of the unprecedented 2018 fire. By the last third of the month, thick smoke filled central California.

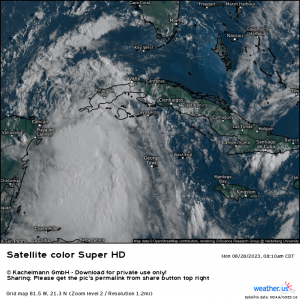

Satellite data from then shows how much of California was blanketed in thick smoke that clung to valleys in the low levels and was whisked into the westerly jet stream aloft.

The dramatic display of mid-August was a warning as much as a disaster. Such lightning storms are extremely unusual, and were probably completely unrelated to either the drought itself or its underlying triggers. However, the resulting conflagration that quite literally smashed the record book wide open proved that the West existed at an effectively ideal confluence of dry fuel and atmospheric support, largely at the hands of the drought. The events of the month to follow would demonstrate accordingly.

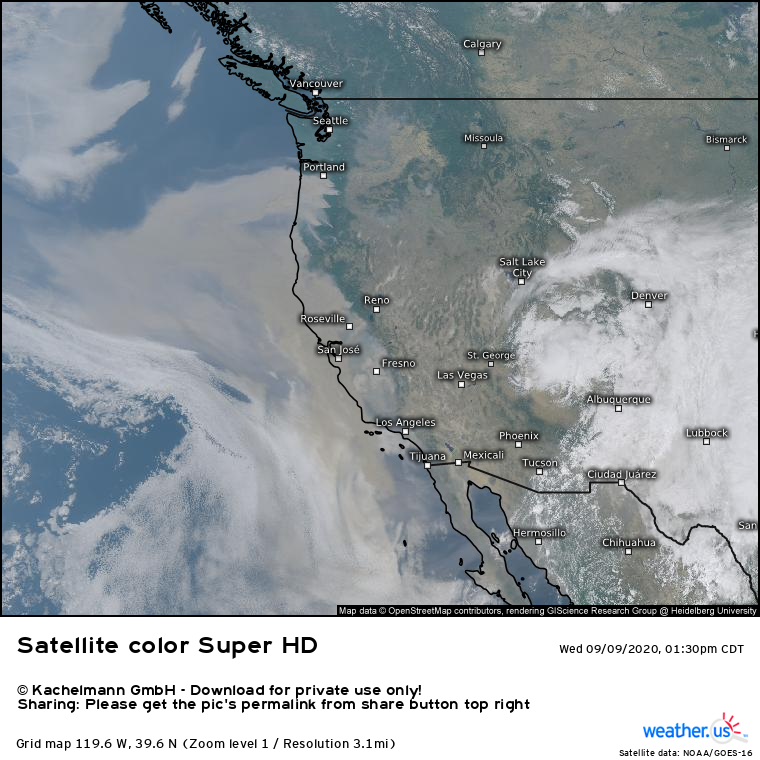

In early September, another atmospheric anomaly allowed a slug of cold midlevel air to slide south along the mountainous West. As a massive anticyclone spilled against the West Coast peaks, a wide ranging offshore pressure gradient forced huge amounts of air to race west, from Washington to California. The result was a roaring windstorm, which whipped air left dry and hot by persistent drought through the forests of the West. In this type of environment, fires could easily grow into massive conflagrations, which is exactly what happened. Ignited by powerlines, gender reveal parties, arson, and unknown causes, huge swaths of the Western forests were all at once up in smoke. One of the most striking weather pictures of all time, in my opinion, show the incomprehensible scale of the fires through the huge smoke plumes that enveloped the West.

The immense thickness of the smoke blanket turned the skies in San Fransisco an apocalyptic shade of orange that day, leading to critical air quality issues. The fires themselves burned millions of acres across California, Oregon, and Washington, with one in California becoming the largest non-complex wildfire ever for the state. The excessive smoke, whisked aloft within an active jet, made the sun appear deep red as far east as New England. I’ve attached a photo I took in Ithaca, NY on the evening of 9/16/2020, showing a haze of high-altitude smoke partially blotting out the sun’s light on an otherwise cloudless day. The fires were almost 3000 miles away.

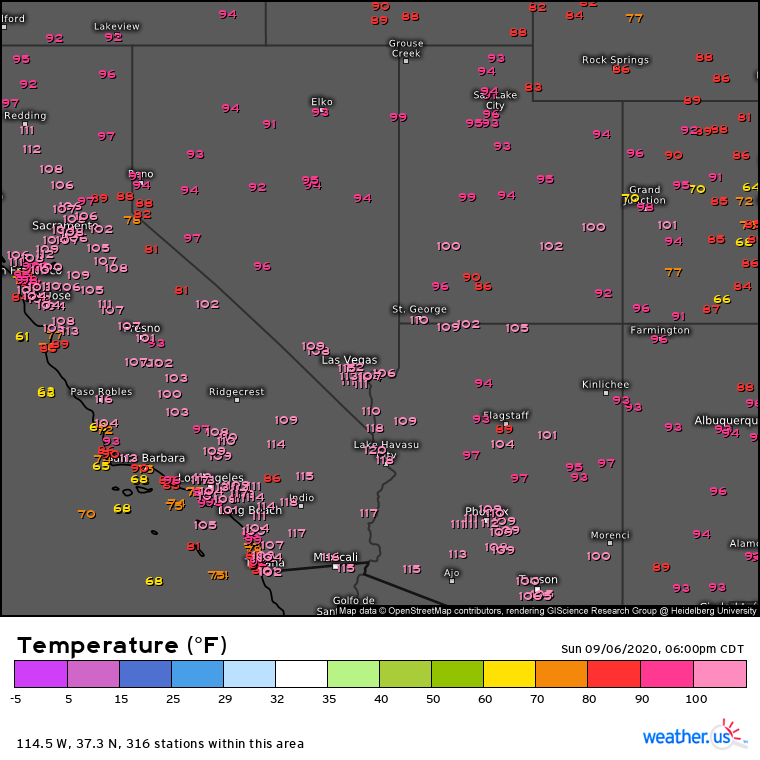

Also in September, an intense midlevel ridge developed over the West, with oppressive heights to 600dam. These ridges are a fairly regular occurrence over the summer in this part of the country and are often seen with heat waves there, but a number of factors including the dry soil allowed temperatures to swell beyond those normally seen. Death Valley challenged all time records for the extremely hot site, while San Luis Obispo saw one of the hottest temperatures ever measured so close to an ocean and stations near Los Angelas broke records for the county.

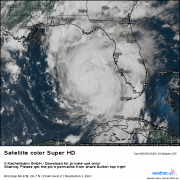

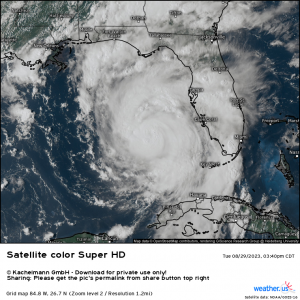

As the West burned all at once and saw extreme heat, heavy snow broke records Colorado, and hurricane Sally threatened to bring a deluge upon landfall to parts of the Gulf coast. Understandably, a lot of people in the weather world (myself included) failed at first to notice the gravity of a slower-fused anomaly in the southwest, near the four corners region.

This part of the West has a wet season almost completely reversed from the rest. Instead of wintertime atmospheric rivers that bring abundant moisture, it is the summertime monsoon that often brings the region more than 50% of annual rainfall. The monsoon itself is a seasonal wind shift, which allows moisture to infiltrate the usually parched Southwest and encourages weeks of scattered thunderstorms to bring significant precipitation to the region. But the process can be finicky, and depends a lot on the placement of surface high pressure systems that can permit or prevent this moisture influx from occurring. Persistently poor high placement meant 2019 had one of the driest monsoon seasons on record, but 2020 completely blew the previous year out of the water. Largely unwavering ridging disallowed the wind shift that typically draws moisture north in the summer, and the season ended up as the driest and warmest on record.

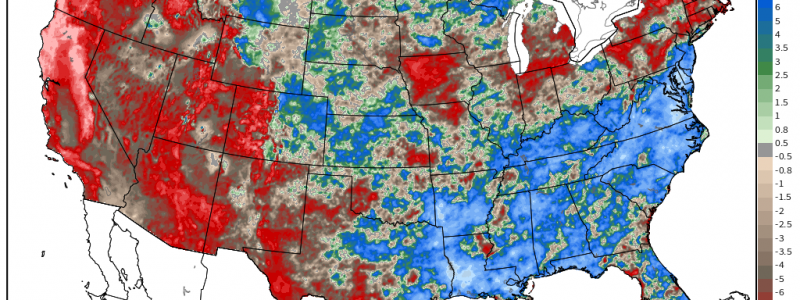

The combination of a dry second half of the California wet season with the monsoon season, parched for the second consecutive year, meant drought was considerably expanding in scope and severity across the West by the middle of autumn 2020. The USDM re-introduced the ‘exceptional’ delineation to large swaths of the region by October, focused over the four corners area. With nearly a full year until the start of the 2021 monsoon, there seemed little hope for improvement at the time, a prediction that has held up well- almost 100% of the West that was under ‘exceptional’ drought to kick off November 2020 is still under the delineation today.

As summer turned to fall, California continued to lurch through a fierce wildfire season. The rain was late to arrive, bolstering offshore flow events driven by continental highs that incited fire outbreaks as late as the middle of November. But finally, the seasonal rain came, and many hoped that perhaps another washout year would crush the re-developing drought that had been responsible for so much hardship. But the atmosphere had other ideas.

The 2020-2021 wet season started off slowly- by late January, most of the West had collected less than half of the amount of precipitation seen by that point on average. A moderately significant series of atmospheric rivers at the end of the month brought significant rain to portions of central California and a great deal of snow to the Sierras, but total precipitation from the event wasn’t as dramatic as expected, and the rest of the winter was drier than average. A loop of midlevel heights over the month of February shows how, despite a more ‘progressive’ pattern than other dry months we’ve looked at, almost all of the troughs that impacted the West did so with such a northerly component that they were unable to bring significant atmospheric river action to the coast.

By the end of March, it was clear the winter had been lackluster yet again. It followed a dry 2019-2020 winter, and two years of monsoons that largely failed to materialize. The warning signs were blaring everywhere by spring: a new chapter in the megadrought was underway.

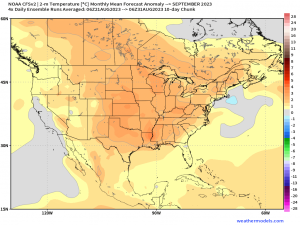

That brings us to today. California is well into its dry season, while the southwest has yet to begin its monsoon season. Already, results of the issues that plagued the wet seasons are becoming apparent. An expansive and anomalous midlevel ridge is promoting excessive heat over a region stricken unbelievably dry. The result is a dangerous heatwave that threatens long-lasting daily records from California to the Rockies. The temperatures, pushed from anomalous to extreme by drought, will threaten the vulnerable and force on all a reminder that this is not normal.

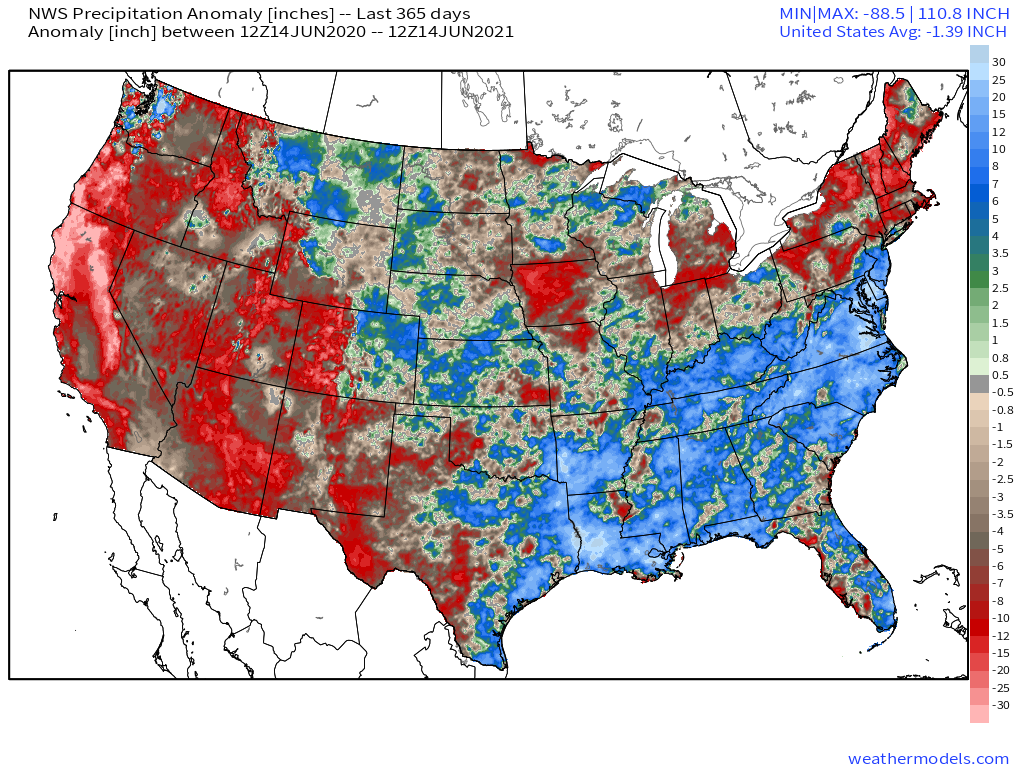

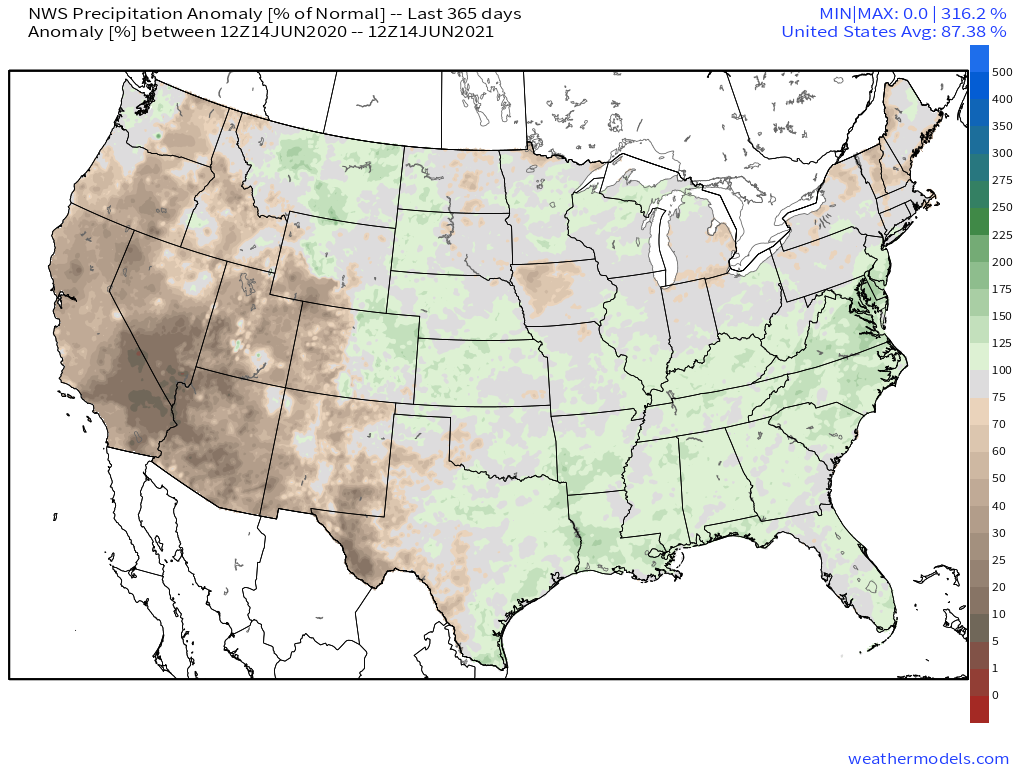

The wet season is a distant memory across the West. But still, every hot and dry day edges deficits higher. At this point, the act of rain not falling is an ongoing catastrophe. 365 day precipitation anomalies across the West are truly scraping the bottom of the climatological barrel. The size of the ‘exceptional’ drought delineation has grown to nearly three times the incredible levels seen in 2014, and an incredibly meager 2.6% of the region is drought free.

The drought is everywhere, and it’s getting worse every week.

This has been part two of a three-part series of blogs on the West’s evolving mega-drought. Part one can be found here. Part three, set to be released on Thursday, will discuss the future of the crisis.