The Grip of a Megadrought, Part 1: A Catastrophe Crawls To Life

Some weather disasters strike with a suddenness rivaled only by their ferocity. They are tornadoes, flash floods, derechos, blizzards and hurricanes; they lash out all at once, pummeling mankind from sunny skies without a hint of foreboding. That we can predict such disasters at all is a testament not to the temperament of the atmosphere but rather to the incredible advances in our science of it, to the talent in those who devote their lives to its understanding. Even still, lead times rarely extend beyond a couple of days, and it isn’t uncommon to hear victims repeat the same common phrase: “it struck without warning, we never saw it coming.” This is almost never meant to attack the scientists responsible for what limited warnings are possible. Rather, it is a testament to the fact that people can wake up to chirping birds and a shining sun, only to have their lives ripped from their hands by sunset.

It is these natural acts of violence that I spend a vast majority of my blog-time writing about. They define the day to day of atmospheric contortions, inspiring watches and headlines, warnings and deaths. In the daily sprint to stay ahead of atmospheric destruction, though, it can be easy to miss the gradual build of a slower-paced disaster.

And then, suddenly, all of the warning signs begin to blare at once.

The United States is staring down the barrel of this type of crawling generation catastrophe. As dry season marches on in the Western half of the country, it is becoming hard to ignore a budding chapter of an unprecedented multi-decade hot and dry spell that threatens to upend an environment that supports massive swaths of population and economy.

___

It is increasingly apparent that much of the Western US, particularly California, is in the throes of a “mega-drought”, a stretch of unusually dry weather that’s been ongoing since the end of the 1990s. In the mid-2010s, the crisis seemed to reach a crescendo as drought to a severity nearly unprecedented enveloped the region. By the beginning of the 2014-2015 wet season, more than 10% of the West fell under “exceptional drought”, the difficult-to-achieve highest level of the US Drought Monitor’s five tier scoring system. At fault was the unusual persistence of ridging off the Pacific coast during the Californian ‘wet season’, in which atmospheric rivers (ARs) caused by slow-to-progress midlevel troughing dump inches to feet of rain up and down the state’s complex topography. These AR events refill aquifers with liquid water, and dump feet of snow at higher elevations that slowly melt into the watershed come spring. Ridges block these ARs, though, preventing an onslaught of rain and snow from replenishing the West before it must bear the hydrological brunt of the hot, dry season.

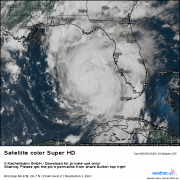

See how this resilient Pacific ridging deflected troughs to the north for three weeks from Dec. 2013 to Jan. 2014, preventing significant AR action and keeping a large stretch of the West’s wet season largely dry.

In the 2016-2017 wet season, however, a pattern reversal from previous years allowed a remarkable sequence of atmospheric rivers to bring temporary relief. Reservoirs across California, many of which were brought to new lows only a year prior, overtopped their dammed banks. In an atmospheric flip that seemed almost purposefully ironic, billions of dollars of flood damage heralded something of an end to a prolonged stretch of intense drought that had, itself, produced consequential and costly ecological and economical destruction.

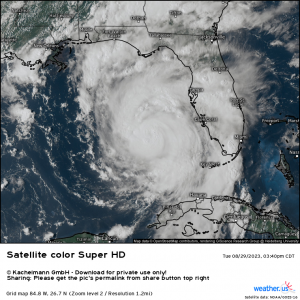

Watch how, sans ridge, midlevel troughs supportive of atmospheric rivers smash into the coast over and over again in 2017. Compare this to the persistent ridging of 2014: this is how to get a wet season that’s actually wet.

The attached loop of more than a month of daily station precipitation data in California over this very wet season shows how a watershed can be replenished following more than a decade of largely dry winters- a number of intense and persistent ARs, touching the whole coast from south to north.

Following this persistent deluge, the USDM was finally able to almost completely remove drought delineation from California. For the first time in many years, the West could breathe a sigh of relief as drought, and the hazards that come with it that range from excessive heat to ecological and agricultural harm to wildfire risk, seemed to at least be stricken from the land. For the first time since 2011, the region had no coverage of exceptional drought.

It didn’t last.

2018 saw the return of anomalously persistent ridging, and the wet season ended up dry basically everywhere. Because of 2017’s boom, though, there was little problem with depleted reservoirs, and high-end drought delineation was slow to return. When it did, by the start of that year’s dry season, it was centered away from California, instead focusing on the four corners region. The ‘exceptional’ delineation even sprouted back to life in this area, away from 2017’s windfall but still impacted by the dry seasons before and since.

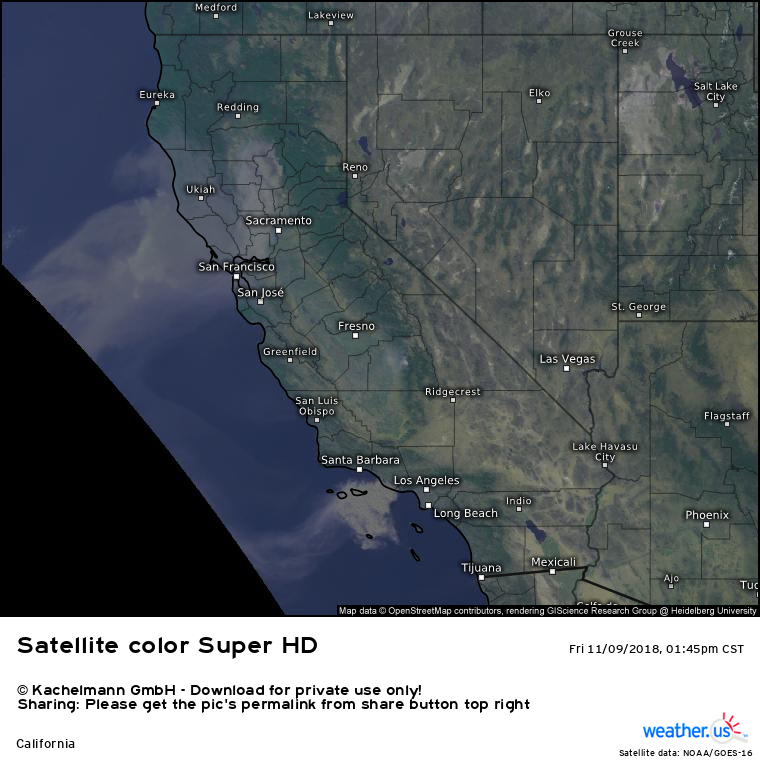

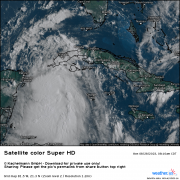

Something else happened in 2018 that signaled a shift into a new era of mega-drought. As dry heat encroached upon parched fuels, anomalously abundant due to the previous year’s rain and historically poor land management, a perfect storm for statewide infernos developed. Dozens of fires from August to November set a new standard for how devastating, newsworthy, and expensive modern wildfires could be, as conflagrations burnt almost 2,000,000 acres, killed more than 100 people, and caused tens of billions of dollars of damage. Particularly noteworthy were the Mendocino Complex, at the time California’s largest ever fire complex, which filled the Valley and Bay with harmful smoke; and the Camp Fire, which rapidly consumed the town of Paradise, killing 85 people and destroying tens of thousands of structures to become the deadliest and most destructive fire on record for the state. Satellite from the latter is shown below, showing expansive smoke plumes drifting into the Pacific. While blame for the disastrous year is multifaceted, it focuses in part on the drought, which encouraged unusually dry fuel loads and soils. The former contributes directly to fire spread, while the latter does so indirectly, by allowing low-RH air that fans offshore wind fires.

Following the devastation of the Camp Fire, which was almost certainly induced in part by drought, the quick approach of the annual wet season surely felt like a relief. This was largely validated by a season above average, although not to the extent of 2017. The wildfire season that followed, while still somewhat notable, was far from the infamy of 2018, likely due in part to higher than average soil and fuel moisture going into the dry season.

But, as 2018 showed, wet years and their lackluster wildfire season counterparts can prove destructive regardless when followed closely by drought.

The 2019-2020 wet season got off to a pretty robust start, with intense storms visiting both North and South California in November and December. A blockbuster low around Thanksgiving even brought record-challenging low pressure to the state. It looked like another wet year could be underway … until January.

January proved to be quite the dry month. But it was February, during which persistent ridging dominated, in which the state recording a month historically dry and warm. For the first time, much of California saw absolutely no measurable February precipitation, and it was one of the warmest months in the state’s history. An early season of above-normal hydrological conditions, precluded by very low drought levels, was immediately jeopardized as the state began falling behind typical water schedule as the snowpack rapidly deteriorated.

January and February are typically the wettest months for the state, and their astonishing dryness left the state in a once again dire acute drought. Reservoirs were low, and snowpack was as close to nonexistent as can be expected in the towering, Pacific-adjacent Sierras. It seemed the whiplash from wet to dry had happened yet again.

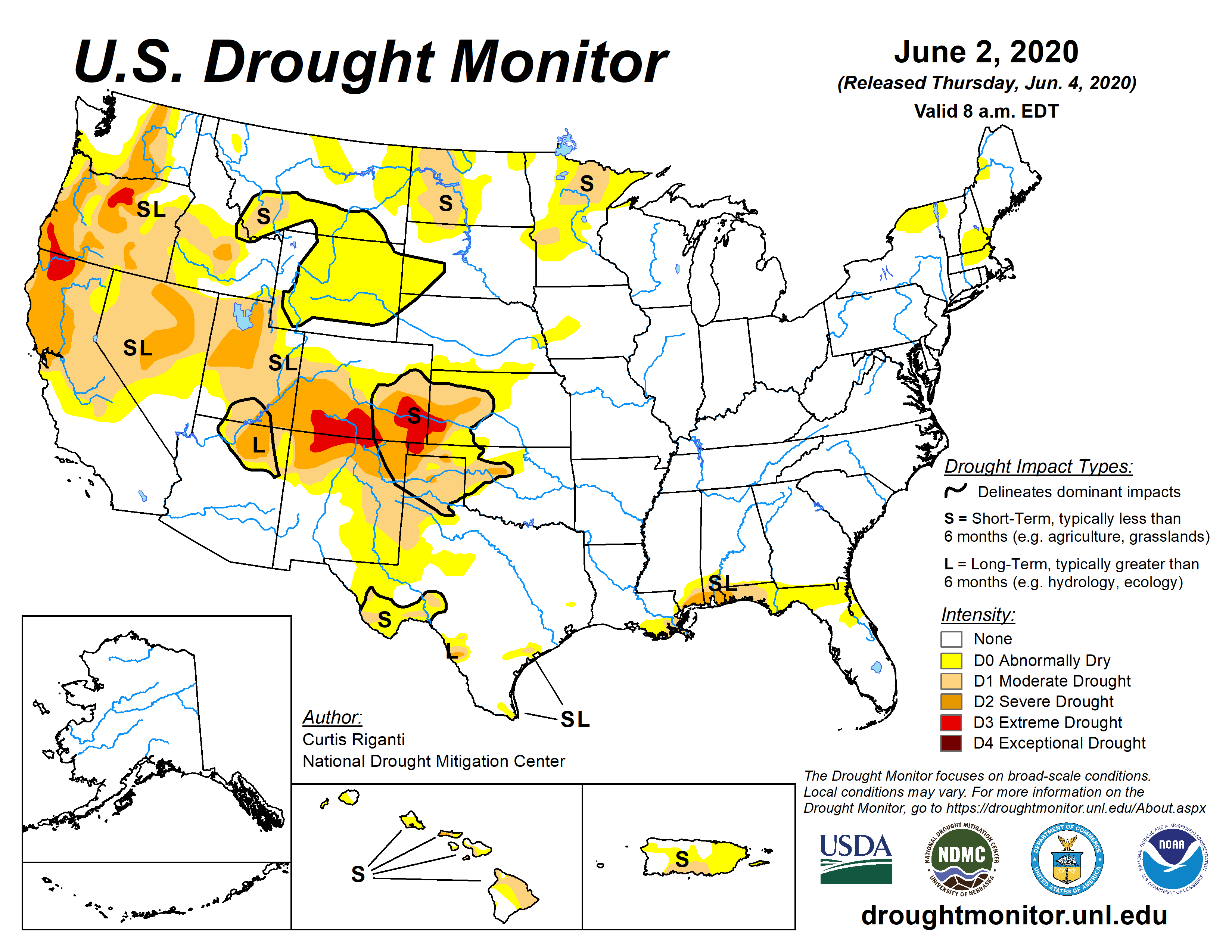

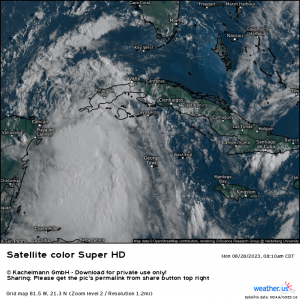

The USDM maps from the middle and end of 2020’s wet season show the rapid growth of drought conditions as the historically warm and dry January and February took their toll on the West’s watershed.

___

The next chapter in the West’s megadrought is the oddest and most devastating. Building off the astonishingly dry and warm end to the 2019-2020 rainy season, an extraordinary fall monsoon and fire season would leave the region reeling, before a dive into a second historically dry winter that would push the hydrological health of the region to the brink.

This has been the first installment of a three part blog series about a potentially disastrous chapter in the Western US drought. Hopefully, it helped contextualize the current dry period. Blog two, set to come out Tuesday, will focus on the year we’ve just had and the region’s present state, and blog three, slated for Thursday, will focus on the outlook and potential ramifications as we head deeper into an unprecedented dry season.