Revisiting the Great Appalachian Storm, 70 Years Later

This week is the 70th anniversary of one of the most extreme, unusual, and damaging systems to ever impact the United States. In the years since, there have been three tornado super-outbreaks, 29 category 5 hurricanes, droughts, floods, ice storms, and even 17 additional RSI-cat 5 snowstorms. The atmosphere has cranked, hour after hour, every single day for those 70 years. But there has never been another storm like the one in November 1950, and now, with ERA5, we can begin to understand why. This article will have a lot of pictures.

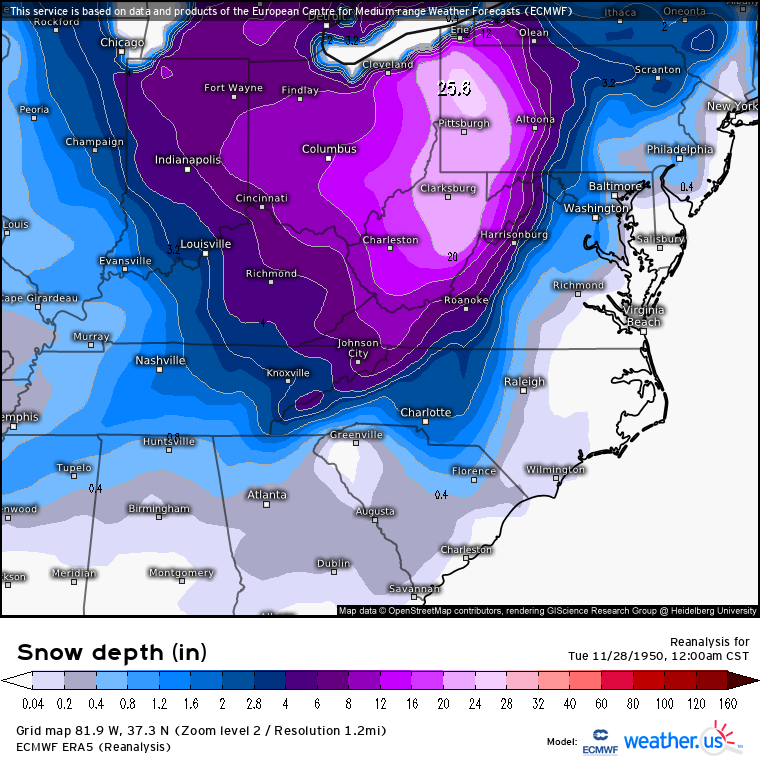

Historical accounts of the storm range from head-turning to borderline absurd. As the system intensified on the 24th and 25th of November, the mid-Atlantic and northeast were blasted with wind. NYC and Newark reported maximum gusts to 94mph and 108mph respectively, and at higher elevations, Bear Mountain and Mt. Washington reported gusts to 140mph and 160mph. Very heavy rain also caused significant river flooding in Pennsylvania, and the massive wind resulted in widespread coastal flooding. On the cold side of the system, frigid temperatures slammed the southeast, with temperatures reaching 5°F in Birmingham and 3°F in Atlanta. Further north, a widespread 2+ feet of snow fell in a swath from east Ohio and west Pennsylvania into West Virginia. In fact, snow in WV locally exceeded 60″!

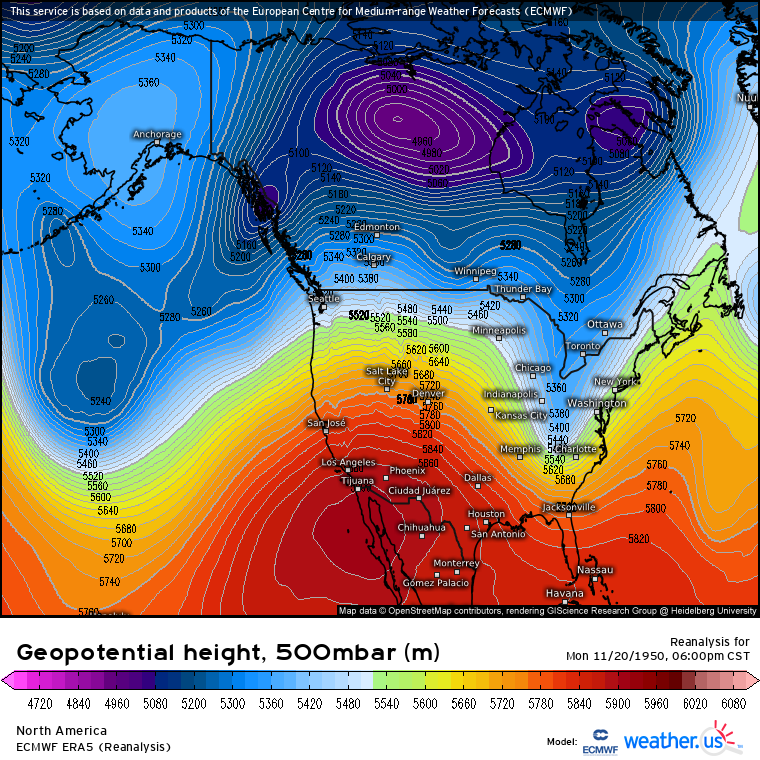

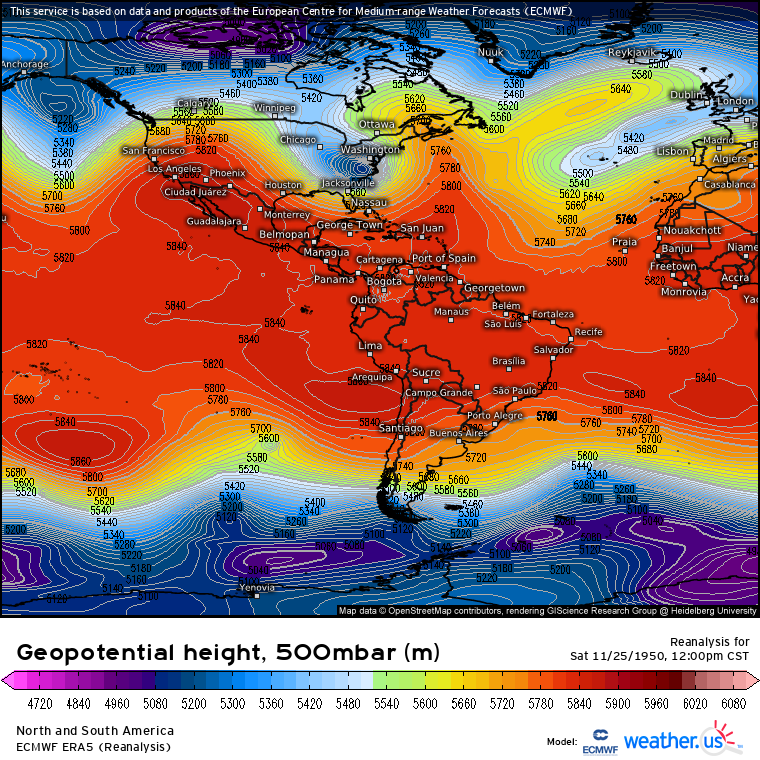

What would become one of the most impactful non-tropical systems in modern meteorology began as a midlevel low rotating south of Alaska partially phased with a significant closed low west of the Hudson bay. This led to an intense, somewhat closed off trough developing, with the center seen here on 11/20 along the coast of SE Alaska.

By the 22nd, midlevel support had cleared the mountains, and surface developments began to take shape. A ~1004mb low was able to develop in a zone of relative divergence near International Falls. But the trough wasn’t oriented all that favorably for cyclogenesis yet, and predecessor troughing had left little baroclinic support at the surface, so the low wasn’t intensifying much. More noteworthy, meanwhile, was the anomalously strong low-level high pressure area that began to sink into the western US, with temperatures reaching -15°F in Montana and North Dakota by 6am on the 23rd.

At this point, the system at the surface looked more like a strong Alberta Clipper than the storm of the century, the kind of low that typically brings the northern fringe of the US a couple inches of snow followed by a few days of frigid temperatures.

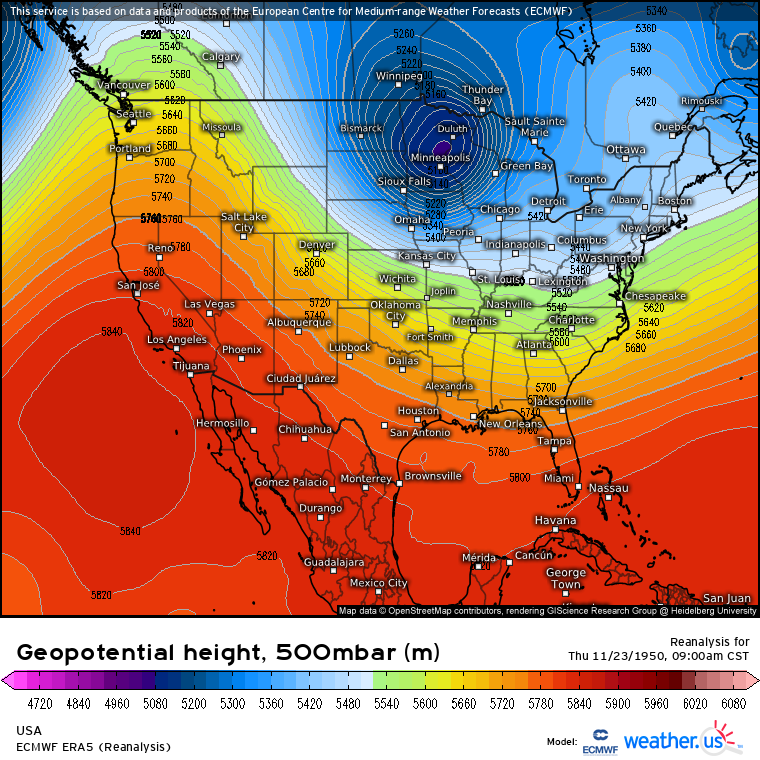

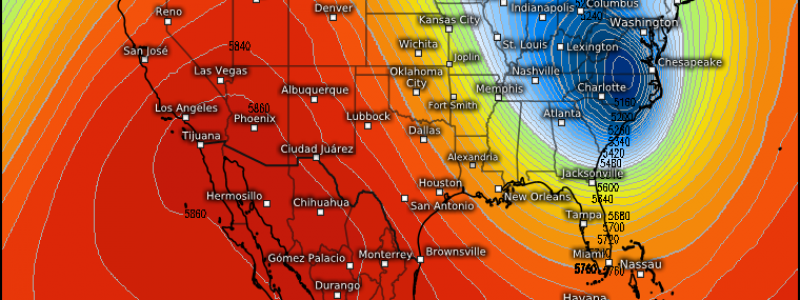

However, the midlevels could not have told a more different story. Steady intensification of our Alaskan trough had occurred as it moved southeast, and by the morning of the 23rd, a fully closed off <5100m 500mb low sat over Minnesota. This is deeper than, for example, the midlevel low that spawned the epic 10/26/2010 954 mb Minnesota surface low, and it was certainly an ominous signal of the massive amount of energy that was moving into the northern US.

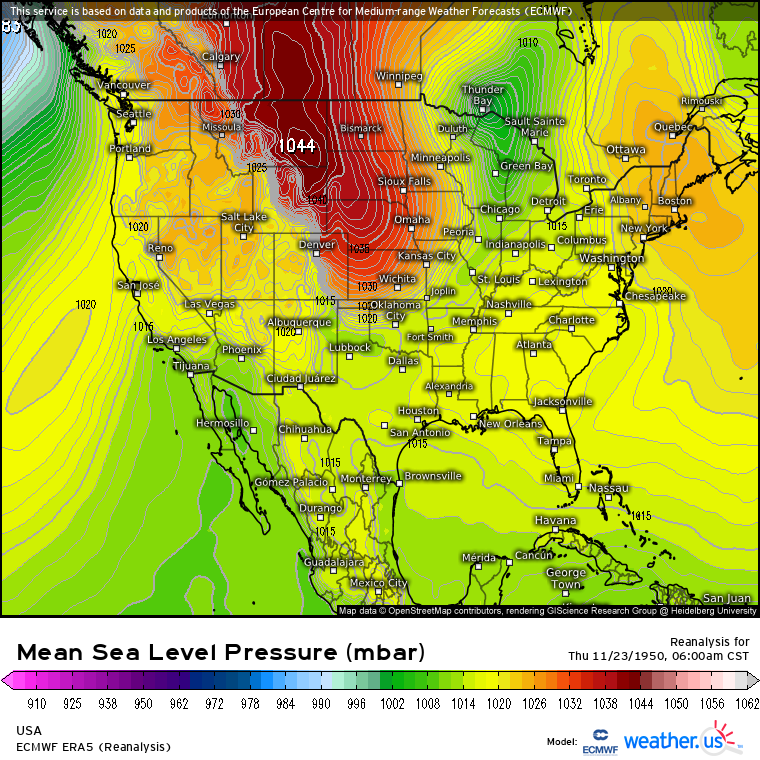

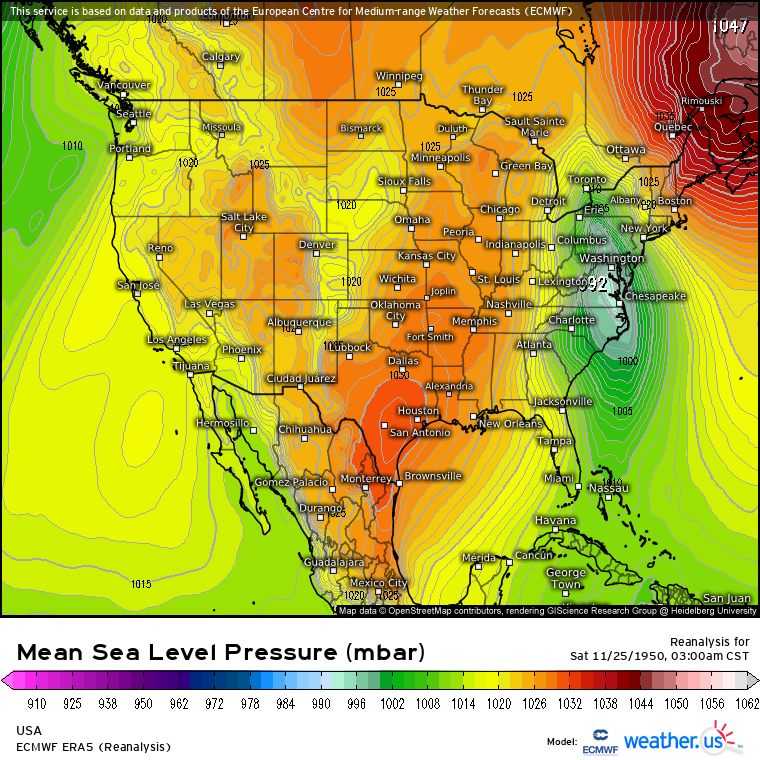

Believe it or not, the following 24 hours were pretty boring across the CONUS. The biggest story was the intrusion of very cold air behind our relatively weak surface cyclone, and the morning of the 24th saw 1040mb pressures at the surface as far south as Lubbock, Texas. The corresponding, already fairly extreme, cold airmass pushed early morning temperatures to the single digits as far south as Missouri.

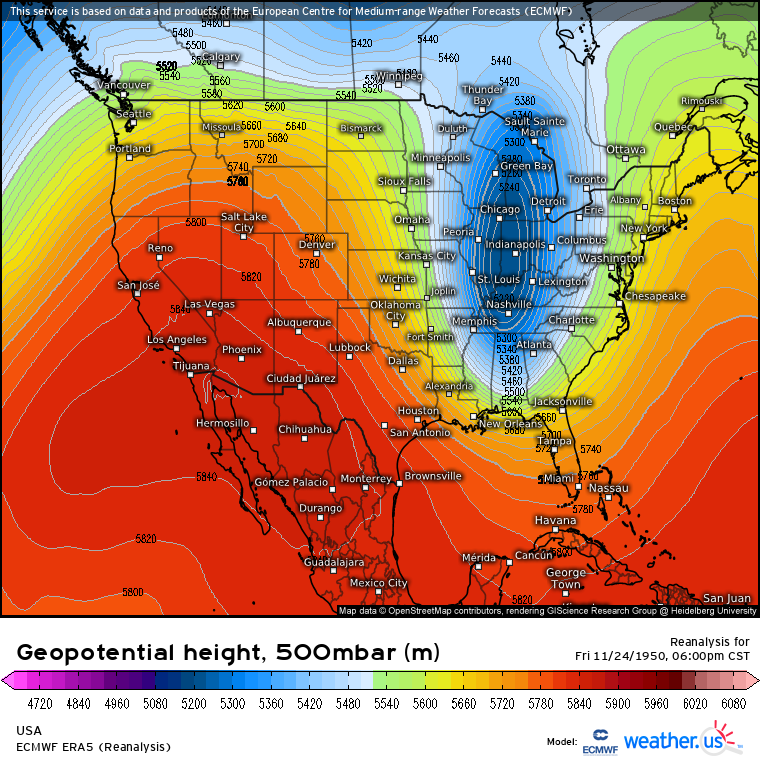

Throughout the day on the 24th, the midlevel low considerably stretched out. By the late afternoon, minimum heights actually increased slightly, but 5500m 500mb heights extended almost as far south as the Gulf. All the while, two important things were happening: the trough was aligning itself into an orientation significantly more favorable for significant cyclogenesis, and blocking over the central Atlantic meant an intense ridge was building downstream over Nova Scotia. The atmosphere was, by 6pm on 11/24/1950, primed to explode.

The stretched out 500mb cyclone’s positioning meant it was able to create significant downstream divergence much more easily. As synoptic-scale lifting intensified in the expansive low’s exit region, pressure falls accelerated along the surface low’s cold front, which was located over the Carolinas. Meanwhile, a significant blocking pattern over the central Atlantic forced ridging to intensify over the eastern Atlantic, and surface high pressure rapidly developed southward towards Maine.

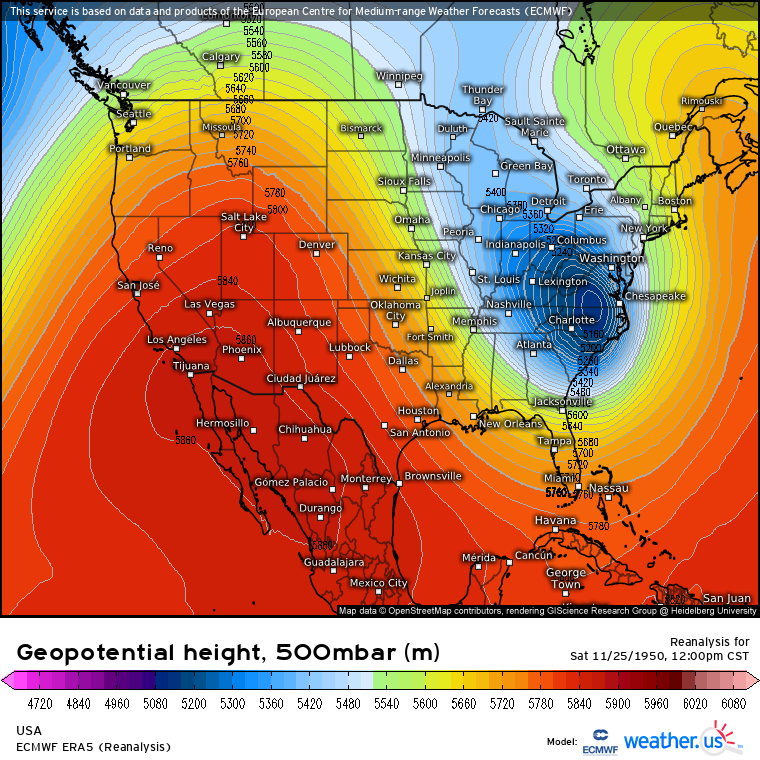

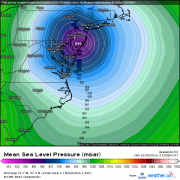

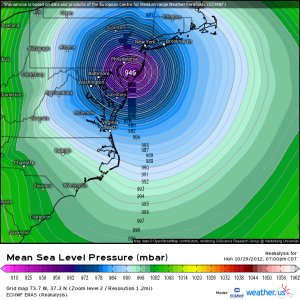

By 3:00am on the 25th, the wheels had come off. Increasing east Atlantic ridging forced the trough at-large to remain stationary, meaning the still-deepening midlevel system had taken on a slight negative tilt as the low slid subtly east of the trough axis. Meanwhile, a more direct result of the ridge’s strengthening were midlevel height rises over Maine that exceeded 20m/3hr.

The result? Where sunset saw a regular cold front pressure gradient, much of the mid-Atlantic was now squeezed between a 1045mb high over SE Canada and a 992mb high over Virginia.

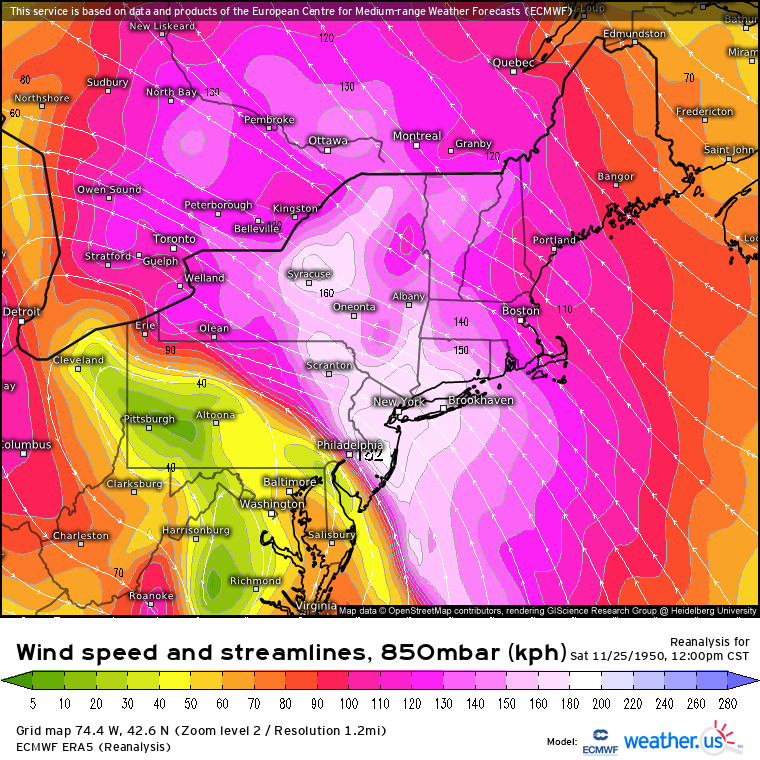

This pressure gradient resulted in an absolutely roaring SW-ly low level jet developing to the northeast of the surface low’s center, which would become the major warm sector weather maker of the system. By 3 am on 11/25, this LLJ was already exceeding 80 knots in the central mid-Atlantic, hosing down the coast with significant moisture and leading to strong wind gusts. For perspective, yesterday’s storm in New England had peak 850mb winds around this 3 am speed. Flow this fast is typically only found a few times a year in the stronger east coast storms, but on 11/25/1950, it only served as a precursor for much worse that was still to come.

As noon approached on the 25th, a fairly ridiculous midlevel pattern had reached a climax of sluggishness over the Atlantic. Strong blocking over the Azores had forced an incredibly impressive ridge into SE Canada, which served to promote very strong surface high pressure development over the area. This ridge continued to prohibit much motion from the US trough axis as a whole, allowing the intense southernmost section to quickly take on a more and more negative tilt.

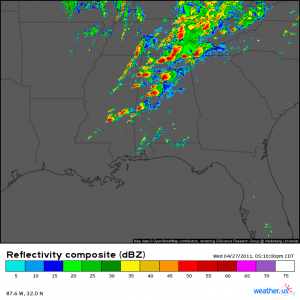

By now, the surface low had intensified to the mid-980mb range, and >1045mb pressures remained entrenched over northern New England. Snow was falling to the low’s west, with moisture feeding from the Atlantic and incredible dynamic support from the powerhouse low sending snow bands into the Ohio Valley. This is also when the low level jet really began to crank, blasting the I-95 corridor with above-ground flow to 100 knots. This continued through the evening, and led to the extreme wind gust reports I mentioned above.

As this LLJ blasted ashore, it firehose’d the mid-Atlantic and northeast with hefty moisture advection from the Atlantic. The result was persistent, significant moisture, lifted into rain along topography and the slow-moving cold front. Where this firehouse remained trained for the longest, over PA, locally significant flooding occurred.

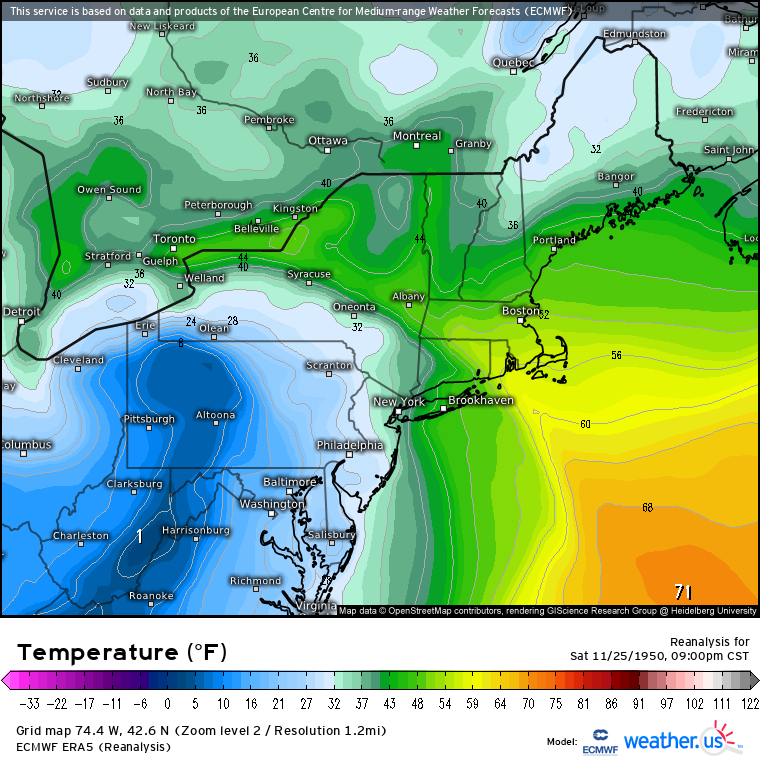

Through nightfall on the 25th, the midlevel low continued northeast while deepening. The extremely cold airmass I touched on before continued wrapping into the low level cyclone’s circulation, where temperatures locally dipped below 0°F. Meanwhile, continued warm air advection along the roaring LLJ meant temperatures remained in the 40s and 50s in New York and New England, creating an absurd temperature pattern over the northeast.

While frigid temperatures surged behind the system’s cold front, the surface low itself burrowed southwest into Ohio, towards the midlevel low’s center, where it effectively stalled for several hours. The extreme cold to the storm’s south and west helped snow fall very efficiently, with whipping winds contributing to blizzard conditions.

Eventually, by early on the 26th, the system had become vertically stacked and began to wind down. Moderate snow, with a degree of lake enhancement, continued to fall behind the surface low as it slowly weakened and pulled north. The slow moving system and intense dynamics had allowed 20+” of snow to fall over a wide swath of OH and PA, with localized amounts exceeding 60″ in WV.

The Great Appalachian Storm of 1950 was a perfect combination of several unusual atmospheric events, featuring wild central Atlantic blocking that coincided with a once-in-a-decade midlevel low. An eastern Atlantic ridge blew up in response to the blocking at possibly the best/worst possible time to both force the midlevel low to stretch and tilt negative and also to push a 1050mb high into Maine. 70+ mb surface pressure gradients from PA to SE Canada allowed extreme wind gusts along the I-95 corridor, and the midlevel low’s slow motion allowed more than 60″ of snow to accumulate in places amidst extreme cold.

A product of a perfect arrangement of atmospheric conditions and topography, the Great Appalachian Storm was truly unique, an event I don’t expect will repeat in my life time.

Sources primarily consulted for the background can be found here and here.