Remembering the Superoutbreak

Ten years ago this morning, across the southeast, the air surely felt counterintuitively both heavy and light. After all, it certainly is not every day that winds blow to 25 sustained knots over Alabama, whipping towards Tuscaloosa and Birmingham before funneling northwards through the Tennessee valley. The heaviness, counterintuitively, came from this same wind, as it pulled the humid, wet gulf air inland with it. The moisture content of the howling air approached record breaking criteria that morning, as did the heat. For anybody old enough to have survived April 3, 1974, the last time anything like this had happened anywhere, the weird wind would have set off deep rooted alarm bells. Even for those too young or new to remember that day, forty years prior, the air would have felt ominous nonetheless in its paradoxical howl.

While wind is simply a symptom of the driving pressure gradients of the atmosphere, the pressure gradients above the Ozarks early on April 27th, 2011, were furious. Over the following 24 hours, a once in a generation combination of atmospheric parameters led to 173 tornadoes that would forever alter the southeast, killing more than 300 people and causing over 12 billion dollars of damage. The death, catastrophic destruction, and meteorological horror show that was about to unfold was written in three day old dry air from New Mexico, and it was written in the moist, hot airmass underneath. It was written in a pronounced thermal boundary, in an unusually discrete storm mode, and in some of the strongest fronts ever seen so late in the spring. More than anything else, though, the tornado outbreak of the century was written in the humid, howling, disastrous wind.

This blog will document the retrospective meteorology of that tragic day, ten years ago. When the outbreak happened, I was ten years old and lived 1000 miles northeast, and so was blissfully ignorant to the catastrophe ongoing. If my writing seems cold, sterile, or overly scientific, know that it is my desire to document the anniversary of a generational atmospheric phenomena without attempting to speak for those who suffered through a disaster inconceivable to me.

To truly understand the atmosphere responsible for the superoutbreak, one must go as far back as 4/21/2011, the day an anticyclone shifting to Florida’s east promoted a southerly component to wind over Mississippi and Alabama. Over the next six days, flow over the southeast shifted under the influence of a series of progressive cyclones and anticyclones, but it remained unwaveringly from the south. This allowed a very deep, moist airmass to gradually build over the region.

Atop this moist near-surface environment, steady southwesterly advection at around 3km above the ground had also been hard at work, responding to broadly cyclonic CONUS flow. The result was a robust EML overspreading the southeast, promoting lapse rates far higher than climatologically normal.

Comparable to a venue being cleaned the days before a big gala, this steady moistening and lapse rate advection laid a groundwork for high-end instability that required additional atmospheric manipulation to explode, but that an outbreak would have been impossible without.

The way I see it is that the atmosphere, primed by incredibly persistent, impressive advection of the two types of airmass that make instability happen, was about as receptive to a potent tornado outbreak as possible. By the time 4/27/2011 actually rolled around, then, the “perfect storm” of the day had already been well underway.

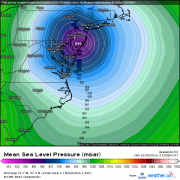

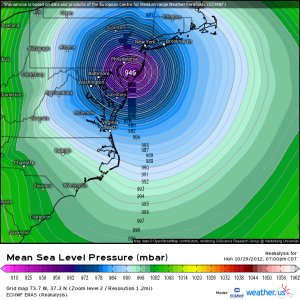

April 27th did, in fact, roll around, as a major-league longwave trough dug into the central US.

The longwave was bordered by a midlevel jet of rare intensity for so late in April, with winds to 50 knots at 500mb basically from coast to coast. Impulses pivoted around the periphery of the expansive longwave for days, which ensured a three day period of incredible activity in the southern and central US.

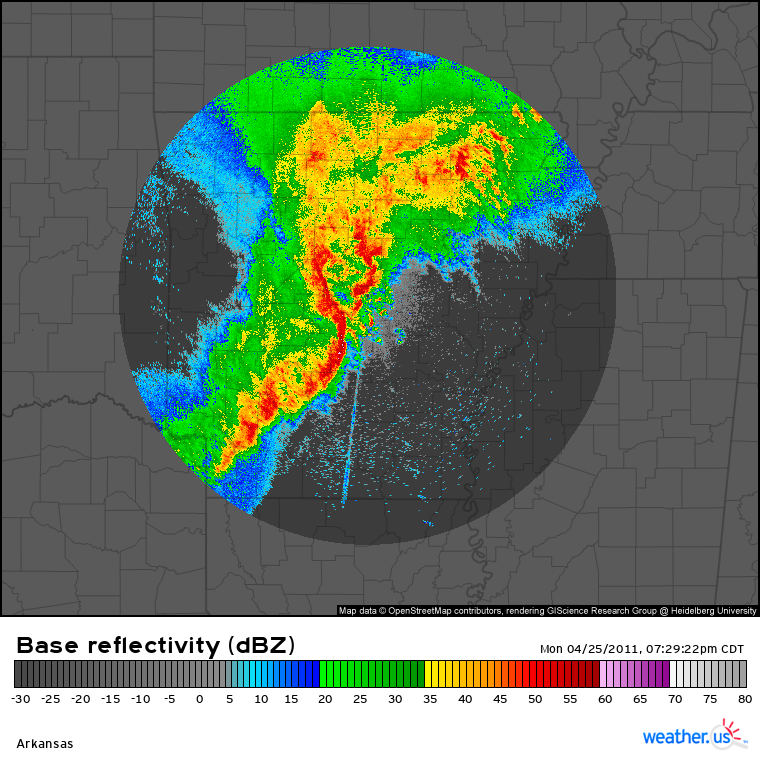

On the 25th, as the first shortwave swung through the south-central US, the baked-in instability was overspread by robust midlevel flow from the approaching longwave. Meanwhile, forcing for ascent to the northwest promoted cyclogenesis near Missouri, intensifying the low level jet over the south-central US. The result was an environment quite conducive for severe weather, and a moderate risk was issued for parts of the region. It verified when, along the stationary front, a robust cluster of supercells brought several significant tornadoes to Arkansas, including a massive EF2 that caused several deaths and widespread damage in Vilonia (a town also slammed by an EF4 7 years ago today).

The morning of April 26th, 2011 saw a deep surface low approaching the Great Lakes. Further south, over TX, a secondary impulse along the longwave’s periphery incited some degree of cyclogenesis, and a secondary surface low began to develop over the state. To the east, along a dryline/stationary front setup, evening storms once again erupted in a highly supportive parameter space for tornadoes. This environment, supported by aforementioned long-fused moistening and a robust EML, was overspread by once again strong low level flow and a powerful midlevel jet. The SPC issued a high risk for the 26th, but somewhat disorganized convective firing and a LLJ that remained modest until the sun set precluded any high-end tornadoes during the day.

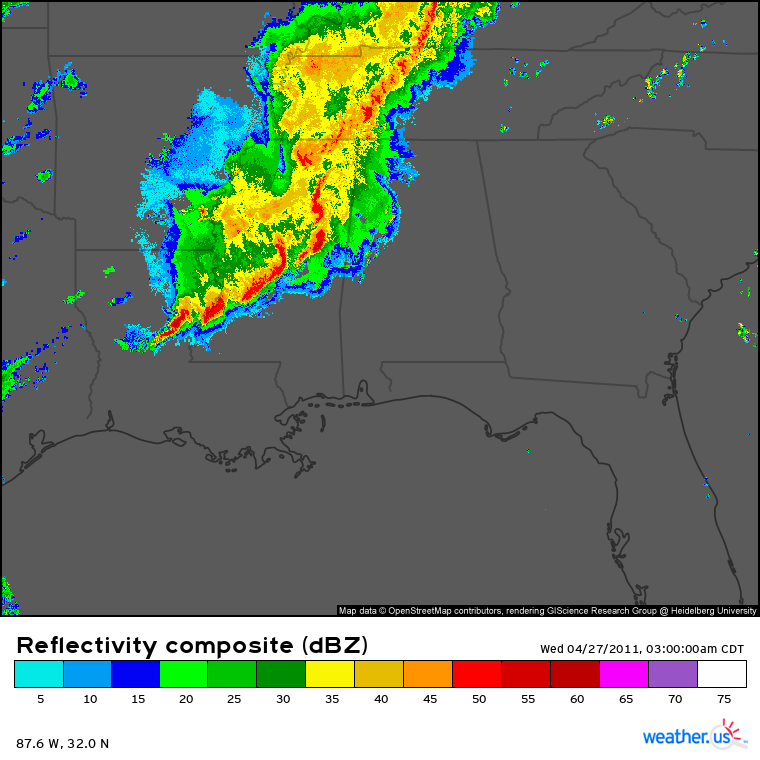

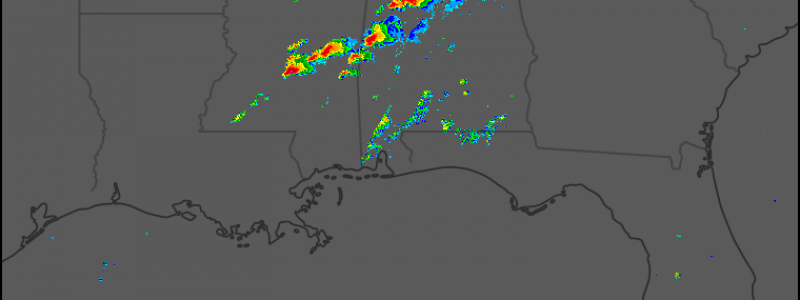

That night, however, the deepening low level cyclone led to a dramatic intensification of southerly flow over the southeast. Storms had clustered into a QLCS earlier, a mode not traditionally very supportive for significant tornadoes. But amidst enlarged helicity, re-enthused moisture advection, a powerful EML, and robust deep layer shear, one of the most widespread tornado outbreaks of the decade was able to occur…. before 8 am EST, as the QLCS swept east.

With the strongest midlevel jet and forcing for ascent still to the west, and daytime heating out of the equation, the destruction that accompanied these late night/early morning storms was ominous to the highest degree. If there was any doubt that the increasingly incredible parameter space could support high-end tornadoes, it was surely whisked away amidst the destructive wind and tornadoes that accompanies the squall line. More than a dozen significant tornadoes, including five EF3s, raked Mississippi and Alabama, and very widespread weaker tornadoes and damaging wind cut power and communications for many in the area. This would compound the chaos of the afternoon to follow, as many were left with few or no ways to receive tornado warnings.

The post-squall line environment over the southeast as the sun rose on the 27th was, briefly, the least conducive for tornadoes that the area had seen in days at the hands of convective overturning. But the strongest midlevel impulse, making up the base of the longwave, was approaching, and tertiary cyclogenesis along the central US stationary front was beginning to accelerate. It would continue throughout the day as the trough took on a neutral tilt and pivoted east, quickly removing midlevel mass.

As heights fell in the low levels of the atmosphere, air already streaming north from the Gulf began doing so with a newfound ferocity, and the low level jet intensified beyond 45 knots by the mid-morning. Dramatic destabilization commenced as EML reinforcements overspread the rapid re-moistening. After all, the southeast was imbedded in an environment that had seen such airmasses transported and strengthened over nearly a full week, remember?

The result was that wind, that terrifyingly humid, brisk wind, as air funneled north from the expansive sea through the valley. Invisible beneath the mostly sunny skies, that wind was a symptom of an environment beyond supportive for tornadoes. The muggy surface air sat dormant for now, but given a nudge, it would rise explosively as all of that moisture condensed, injecting latent heat into an atmosphere that cooled far faster with height than a parcel could. This dramatic upward acceleration would occur within an atmosphere racing counterclockwise with height in the curvature of warm air advection, from southerly and 25 knots at the surface to southwesterly and 50 knots one kilometer above, to westerly and 80 knots in the midlevels.

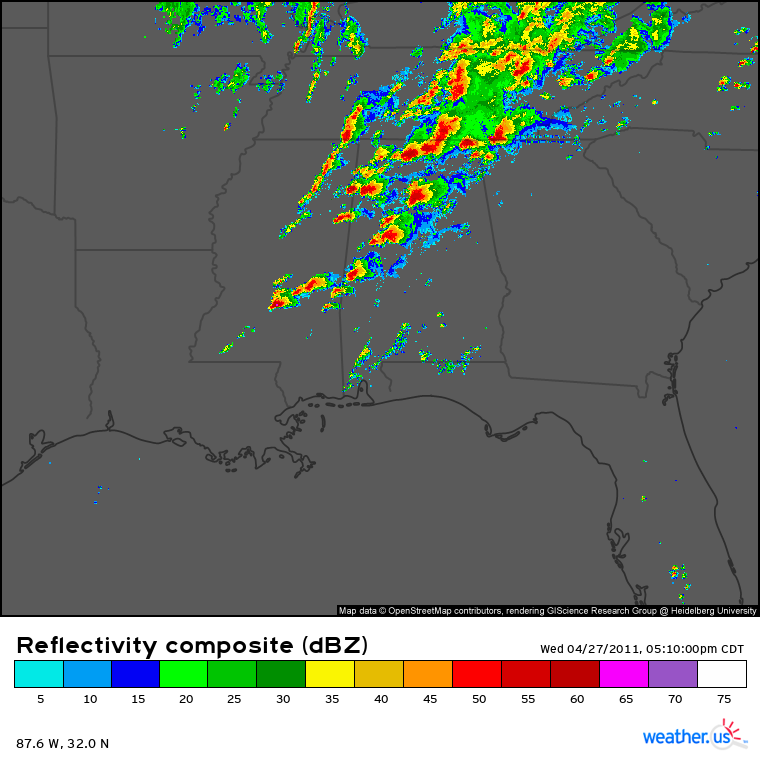

That nudge came as a cold front, responding to the quickly deepening surface low over the central US, swung east in the mid-afternoon. With storms tracking nearly perpendicular to the front, into an environment perhaps ideal for tornadoes, something that really hasn’t been seen in decades of modern meteorology happened that afternoon: lines of supercells developed.

Intense rotation in many of these storms, at the hands of an effectively perfect storm of atmospheric conditions, dropped high-end tornadoes. More than one hundred and seventy tornadoes did touch down* from the morning onward, a shattering new record. Among these, a very high proportion were significant or violent, with 21 EF2s, 15 EF3s, 11 EF4s, and four EF5s.

This is truly a staggering statistic, and if you weren’t just floored, I encourage you to feel it out for a minute.

There were four EF5 tornadoes that afternoon. Since then, there have been three. Before, since the scale’s 2007 introduction, there were two. In other words- if you pick an officially rated EF5 tornado at random, there’s a 45% chance it would have happened in a six hour window.

There were also 11 EF4 tornadoes. In the decade since, no ~year~ has had that many. In fact, there were only ten EF4 tornadoes, one less than the superoutbreak’s afternoon, from 1/1/2015-12/31/2019. This is, I think, the most completely staggering statistic of the outbreak.

* I know “tornadoes touched down” is repetitive, but I like how it sounds in my head, and you all know what I mean anyway

Info sources: mostly SPC, also Wikipedia for some stats