Forecast For Weekend East Coast Storm Remains Uncertain

Hello everyone!

All eyes this week will be on the potential for a strong storm to form off the East Coast sometime this weekend. On Saturday, I took a deeper dive into the sources of uncertainty in the forecast including the behavior of certain small-scale upper level disturbances. That analysis was a bit “in the weeds” but it yielded some useful insights, the practical implications of which I’ll discuss in this post. Of course there are still plenty of uncertainties in the forecast being 6-7 days out, but we’re definitely making some progress in the right direction.

One of the questions we had back on Saturday regarded the strength of what will end up becoming the southern disturbance involved in the storm’s formation. I explained in a twitter thread how the strength of a disturbance that will move onshore tonight (1/27/20) likely will play an important role in determining the timing of the storm. A faster/weaker disturbance now would likely lead to a faster (and possibly weaker) storm next weekend, while the opposite would also be true.

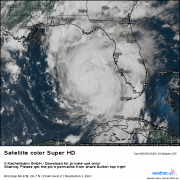

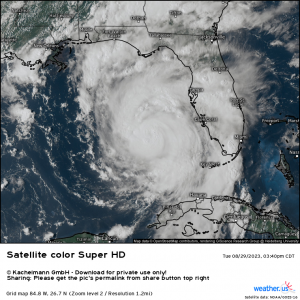

A quick check of GOES-West WV imagery this morning highlights the disturbance in question which is currently swirling west of Portland Oregon. It’s pretty clear that this system ended up emerging from the Central Pacific on the stronger side of the range of possible outcomes. As a result, it’s much more likely we see our storm form Saturday/Sunday as opposed to Friday/Saturday.

Have we made similar progress identifying the storm’s likely track?

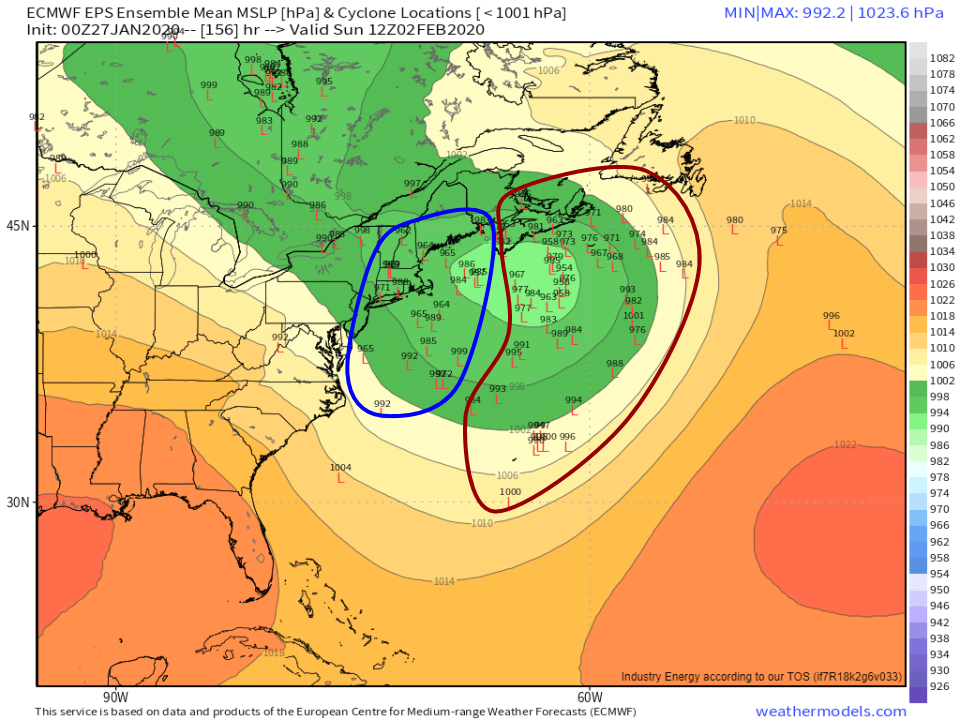

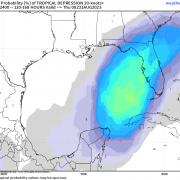

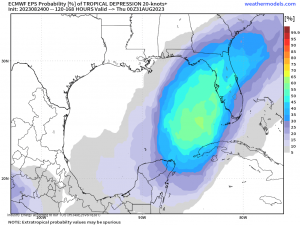

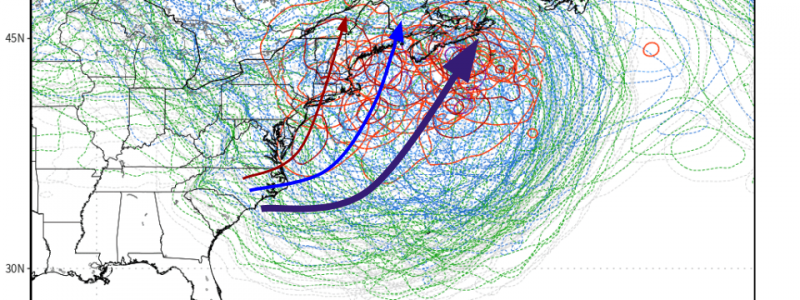

Ensemble guidance (read more about ensembles and why they’re useful in this post) is now pointing more strongly towards a farther offshore track that could bring significant snow to Nova Scotia but would be too far east for the US East Coast. In case the spaghetti plot shown above is a bit too noisy, the map of individual ensemble member low location forecasts highlights the same point in a slightly different (and perhaps clearer) way.

Notice the bifurcation in ensemble solutions with one cluster remaining close to the East Coast and another (larger) cluster forecasting a low track well offshore. A track that splits the difference, while roughly reflected in the ensemble mean forecast, is perhaps the least likely outcome of them all which further reinforces the importance of examining ensemble data on an individual member basis.

Now that we know ensemble guidance is showing greater odds of an out to sea solution, we should ask why that is, and if this physical explanation makes sense in the context of other available observations.

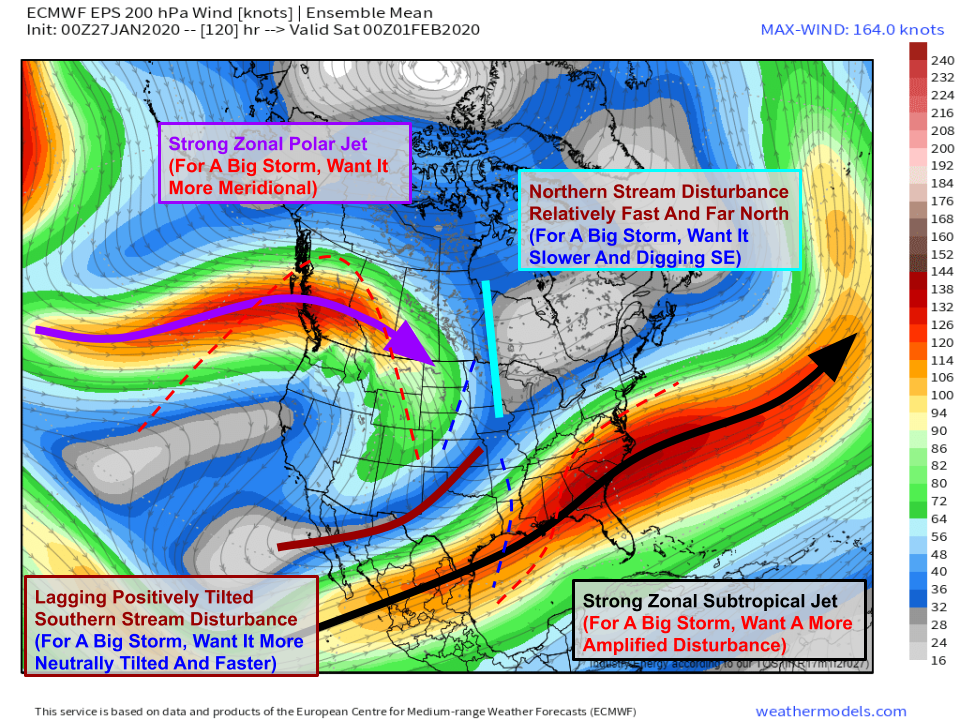

This map shows the EPS mean forecast for 200mb (jet stream) winds. Comparing this forecast with a conceptual model of what this map should look like ahead of a big storm, a few key issues jump out. First of all, the whole pattern is characterized by strong zonal (west->east) flow, and waves embedded within that flow are relatively low-amplitude. While it’s not impossible to get a storm in a pattern like this, it sure is a lot harder. The reason is that when you have strong zonal flow, it becomes really hard for northern stream disturbances (they have the cold air) to detour south for a rendezvous with southern stream disturbances (they have the moisture) because both systems are being pushed to the east by the zonal flow. While it’s not impossible for the southern stream system to make a left and head up the East Coast (that’s what some guidance suggests), it’s very hard for everything to come together correctly.

While this forecast of strong zonal flow would certainly inhibit our storm chances, is it actually likely to verify?

A quick glance at full-disk WV imagery from GOES-West (the north-south oriented dry slot in the upper right corner is located over AZ/NV for reference) shows a very strong zonal jet stream extending all the way from Asia to California. While the jet won’t remain exactly in this configuration for the next week, the presence of this feature currently certainly gives additional credibility to forecasts of continued zonal flow next weekend. Like anything in the universe, the atmosphere likes to keep on doing what it’s doing now unless there’s some outside force to shock it into doing something else. There are certainly outside forces that can shock a zonal jet stream into becoming more meridional, but those forces tend to operate at timescales longer than the 3-5 days we have before the disturbances in question are either properly aligned or not.

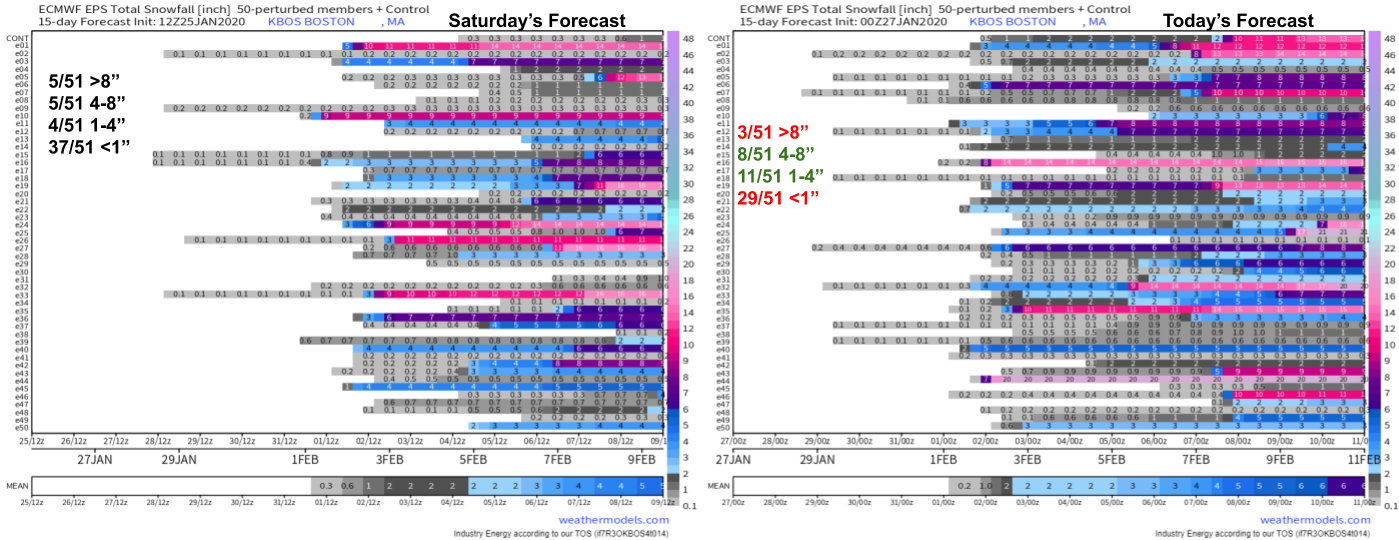

In Saturday’s post, I ended by looking at the EPS ensemble forecasts for snowfall in Boston MA. While only one city, it serves as a fairly good proxy for the relative odds of a storm. If such a storm were to form and move close enough to impact the US, it’s pretty likely that Boston would end up with some flakes. The exact same plot can be generated for most cities at weathermodels.com, and similar plots can be generated for every town (even the really small ones!) at weather.us.

Here’s a quick comparison of EPS forecasts from Saturday and the same forecast made this morning. I’ve included the breakdown of how many members fall into each snowfall category, not because I think they do a great job predicting snow totals even if they nail other aspects of the storm’s forecast, but because I think that distribution is a reasonably good proxy for the odds of a low/moderate/high impact storm. On today’s forecast, I’ve color coded those categories by their change in size from Saturday. The odds of zero-impact snow and high impact snow have both gone down, while the odds of a moderate event have increased a bit. While I’m not totally sold on every aspect of that trend, I do agree that the odds of a major storm are relatively low. Furthermore, I think those odds likely stay relatively low unless there’s a compelling reason to think that we’re able to move away from a highly zonal jet configuration.

Of course I’ll continue to update this forecast as we move through the week, especially if it looks like we will manage to pull off a higher impact event.

-Jack