A Stormy Weekend Ahead On The East Coast

Hello everyone!

With generally quiet weather expected across the US today, the focus of this post will be a little further out in time than usual. A large storm system is forecast to develop off the East Coast this weekend, and could bring significant weather from the Gulf of Mexico all the way to Maine. Depending on exactly how the system evolves, heavy rain, gusty winds, coastal flooding, snow, and mixed precipitation could all post threats to parts of the East Coast. This post will take a look “under the hood” of this storm threat, and will discuss not just what I expect to happen, but also why, including why the pattern is generally favorable for a storm, but also what inhibiting factors will likely prevent this one from being a monster.

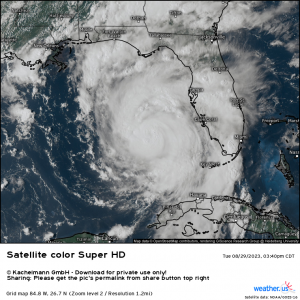

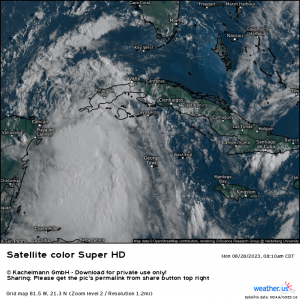

Here’s a look at this morning’s water vapor satellite imagery, which gives a good overview of the current pattern. I’ll run through a few of the more notable features from west to east, as the much of this post will be about the pattern setup, then why that is/isn’t supportive for a large storm. In the Gulf of Alaska, a strong storm is pushing warm/moist air north. This is building a large ridge over the West Coast under which several disturbances are trapped. The strongest of these, an upper level low SW of Tijuana Mexico, is guiding Hurricane Willa towards the Mexican coast. Meanwhile to the east, a trough is being carved out across the East in response to the Western ridge. Embedded within this larger trough is a strong disturbance centered near Toronto. Feeding into this disturbance is a seasonally impressive tap of Arctic air. Moving into the Atlantic, a weak downstream block (low pressure near Newfoundland, high pressure to its northeast) is seen along with signs of a strong Azores high in the Subtropical Atlantic.

Overall, this is a pretty classic “predecessor pattern” for East Coast storms with a building Western US ridge, and digging Eastern US trough.

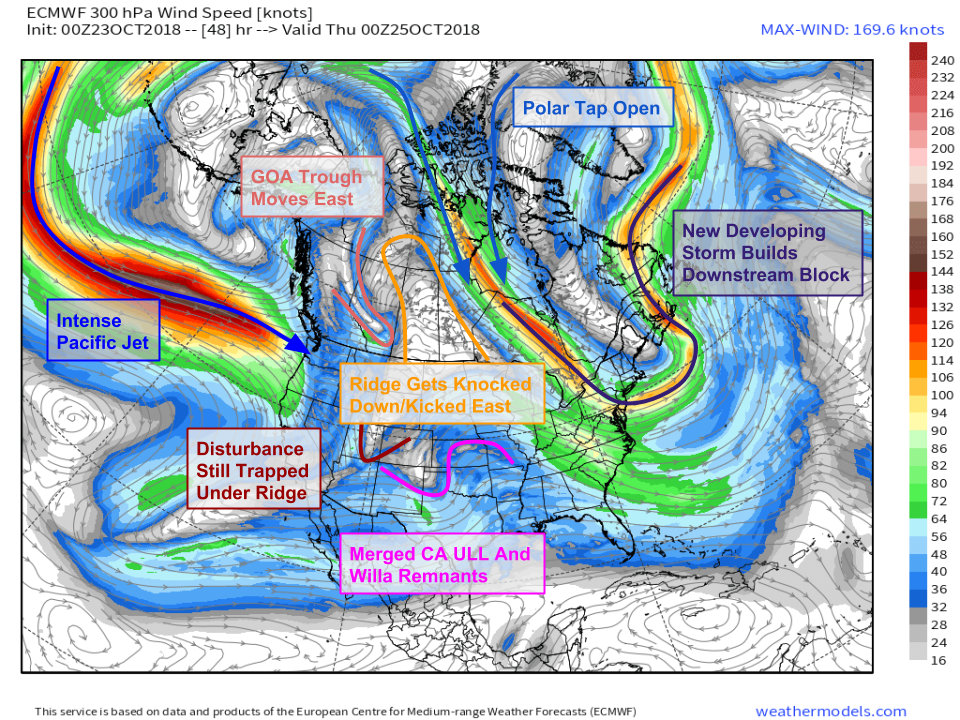

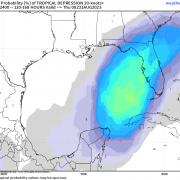

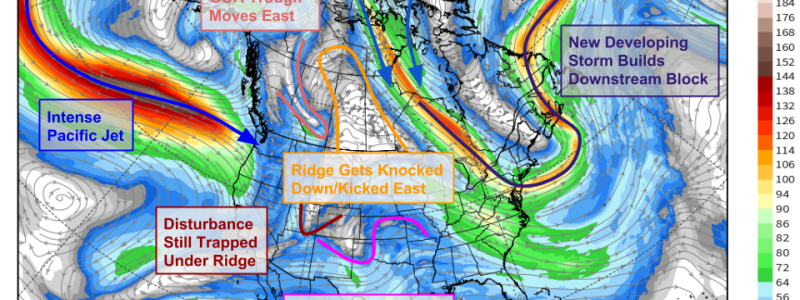

Here’s what the pattern looks like tomorrow evening. There actually is a coastal storm set to develop tonight, and if the calendar read December or there was a bit more downstream blocking, we would have already been talking a lot about it. However, it turns out that this initial system is going to set up a newer and much stronger downstream block, after it brings some snow to Northern Maine. Meanwhile in the West, our pattern is no longer looking so good. The GOA trough that is currently helping build the ridge will be breaking it down as it moves into Alberta. This eastward movement of the trough (and as a result, the ridge) will be driven by a powerful, zonally (east-west) oriented jet extending from the International Date Line to Seattle. Meanwhile to the south, we see two disturbances meandering over the Southern Plains. These will go on to be part of the larger storm system this weekend. Map via weathermodels.com.

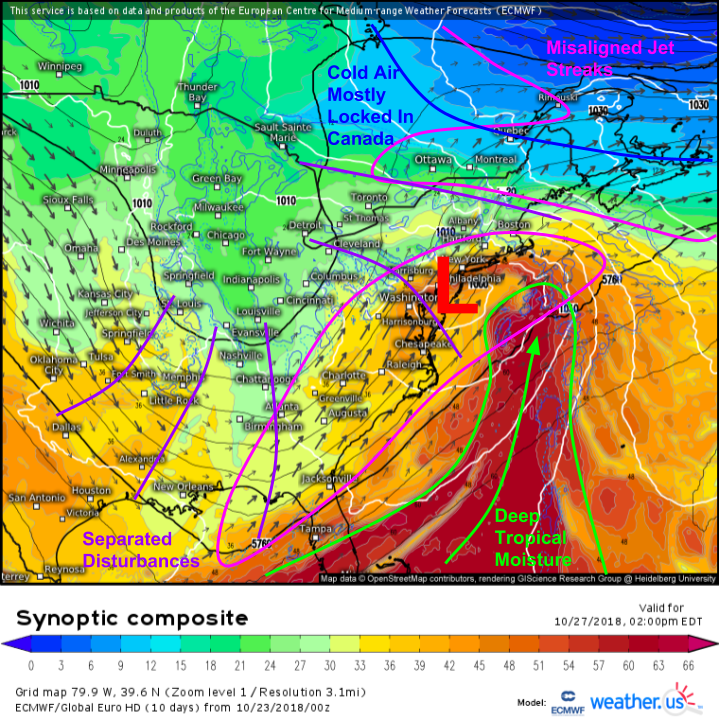

Here’s yet a third way of looking at the pattern, at yet a third time (Saturday morning) but note the general idea remains the same. The ridge in the West has been flattened by the strong Pacific jet, our strong downstream block has developed over far NE Canada, and disturbances are converging on the East Coast within the framework of a broad, negatively tilted trough. At a quick glance, this pattern appears generally favorable for an East Coast storm, and it is, but once we start looking a little more closely at the particular processes that need to unfold for that storm to actually come to fruition, some problems become apparent. Notice where all our disturbances are located. They’re scattered across the continent, and are remaining separate. Also notice the westerly winds (not northerly) over Canada. Our Arctic tap has closed, leaving out storm cut off from deep cold air. Map via weathermodels.com.

If we take away some of the “noise” on that map (the vorticity is valuable information, but sometimes it makes subtle features a little hard to see), we can see this separation more clearly. Each blue line is a “short wavelength” (shortwave for short) disturbance pinwheeling around the long wavelength (longwave) trough. Notice how each of the shortwaves is separated by a few hundred miles. This means the energy associated with the overall longwave trough isn’t consolidated in a small area, but instead is spread out over the entire eastern half of the North American continent. A diffuse energy distribution will, perhaps unsurprisingly, lead to a diffuse storm system, which is exactly what I expect. Map via weathermodels.com.

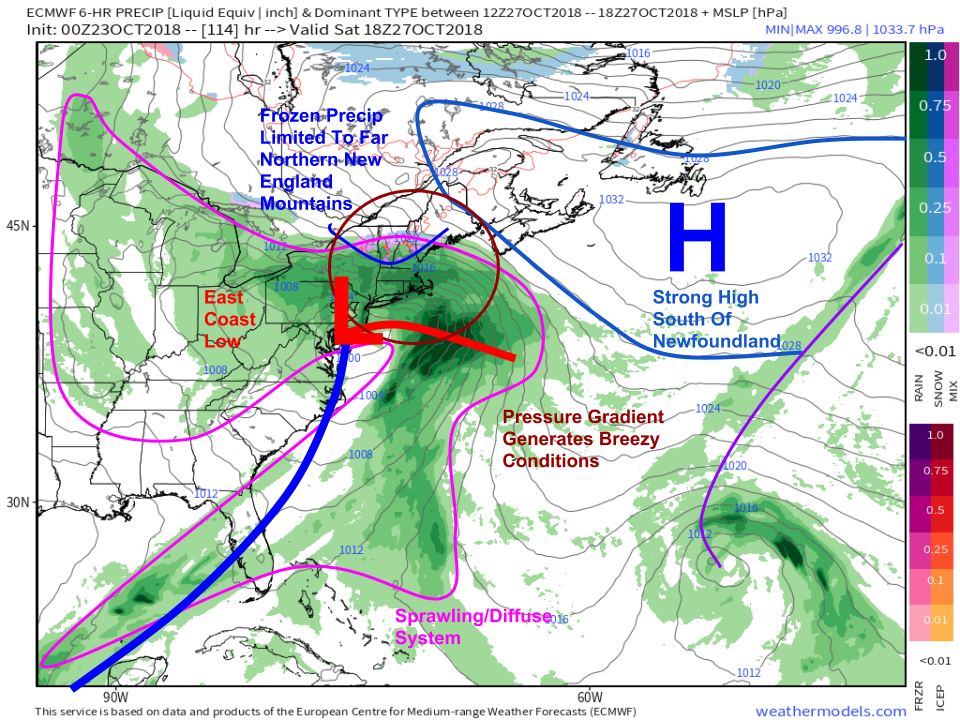

Here’s what that looks like on the surface map. Note the large but shallow low pressure system, and its even larger but even weaker precipitation shield (pink). Gusty winds on the front side of the system will come not from the storm’s dynamics, but from the gradient between the weak low and a very strong high south of Newfoundland. Additionally, having been cut off from any supply of deep cold air, our storm is producing mostly rain. The one exception will be the far northern mountains of New York/New England from the Aridondacks through the Greens and Whites up into Northern Maine. A mix of snow and sleet is likely to fall here, depending on the exact temperature profile. Map via weathermodels.com.

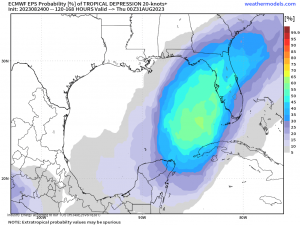

A look at the ECMWF’s synoptic composite map adds a little more context to some of the features we’ve already discussed. Despite the weak dynamics, the storm will have access to some fairly deep tropical moisture, meaning that some heavy rain is possible especially from Philadelphia northeast through Southern New England. The jet streaks associated with this system are also poorly aligned, with both jet streaks anticyclonically curved. While the left exit regions of straight (west-east) and cyclonically curved jets are supportive of divergence aloft, the divergence in anticyclonically curved jets is primarily focused in the right entrance region, located near Tampa Florida. The right entrance region that is present in the vicinity of the storm isn’t powerful enough to drive substantial intensification, but should be enough to get a decent precip shield going.

Here’s a loop of surface maps from late this week (Friday) through early next week (Tuesday. Notice the three storms forming off the East Coast. Each time one or two of those disturbances approach the coast, a new storm forms, but each storm is fairly weak, seeing as it has only one or two disturbances worth of energy behind it. While not overly important to the forecast/impacts, I like this animation because it shows the surface-level effects of the separation in disturbances aloft. Imagine if we’d gotten all three of those storms to join forces! GIF via weathermodels.com.

With the diffuse/weak nature of this storm now thoroughly covered, let’s briefly discuss impacts. I won’t go into too much detail here, since there’s still time for the forecast to shift around a little bit. While the storm itself won’t be all that intense, the pressure gradient between the Canadian high and the storm will produce some breezy conditions for areas that don’t have to deal with the effects of friction. However, because there won’t be any strong dynamics due to the storm’s weak/diffuse nature, those strong gusts won’t be able to really make it down to the surface in areas away from the immediate shoreline and ridgetops.

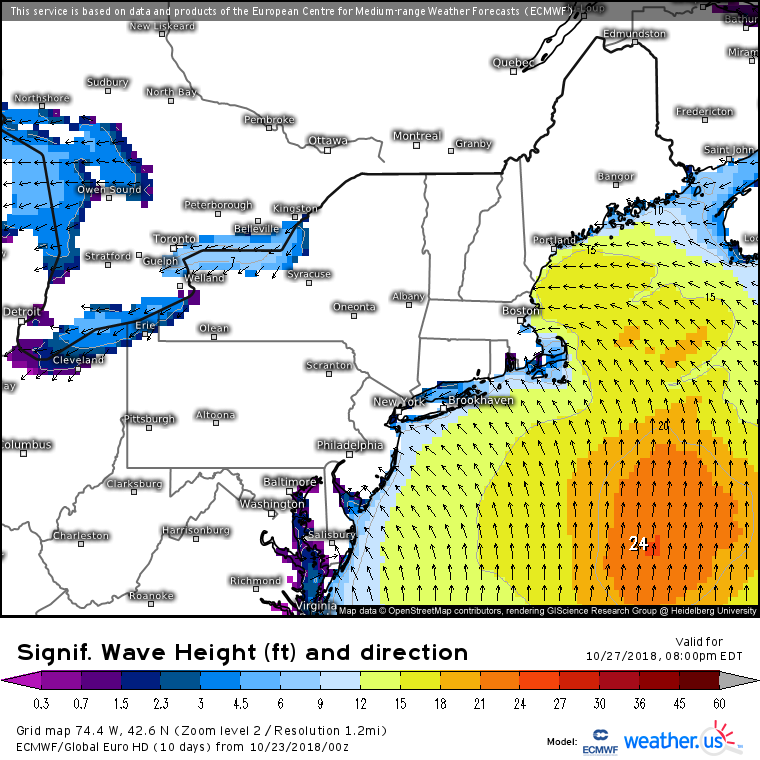

Those breezy winds will kick up some rough seas. While there won’t be any major flooding, watch for splashover/minor inundation at high tide in typically susceptible areas. Beach erosion will also be a concern, especially north of Nantucket.

I’ll have more updates on this storm as we move through the rest of the week, both here and on twitter @WeatherdotUS and @JackSillin. Also follow @RyanMaue for forecast updates and news about weathermodels.com!

-Jack