Looking Back on Sandy: Ten Years Later

Ten years ago tonight, the eastern seaboard, more specifically New York and New Jersey, watched warily and rushed preparations to completion as Hurricane Sandy lurked not too far offshore.

Do you remember where you were?

I certainly do. I was still living in Northeast Pennsylvania, where I grew up.

We were concerned. Concerned the Susquehanna would flood again. We were still recovering from a close call barely a year prior when rains from Tropical Storm Lee brought our river to a record crest of 42.6 ft. The levees and floodgates had held – but barely. Many were still cracked from the stress of the water and in need of repair. We lived in the floodplain for the Susquehanna and had evacuated in 2011. Would we need to evacuate again?

Additionally, we worried about power outages. Temperatures were forecast to drop to near freezing after Sandy pulled away. We knew any outages would likely take a long time to resolve due to the size of the storm and expected impacts.

Even though we had legitimate concerns, they were nothing compared to what our friends and family were facing closer to the coast. The potential for storm surge in excess of 10 feet and hurricane force winds was a daunting thought. The last hurricane to impact the East Coast was Hurricane Bob in 1991 – 21 years prior. Bob had made landfall in Rhode Island, though. New Jersey had been on the western side of that tropical cyclone and removed from the impacts the core brings.

New Jersey’s booming tourism industry with many popular locales built on fragile barrier islands severely complicated the situation – and made the need to evacuate even more urgent. When you have a beach paradise built on barrier islands that are perhaps 7 ft or so above sea level and you’re expecting storm surge of 5 to 7 ft, well, that’s a problem.

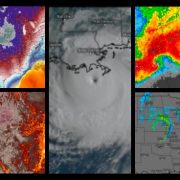

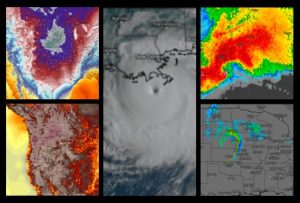

Anyway, we all know what the aftermath looked like. Despite my long introduction, this blog does have a purpose. On the eve of the 10th anniversary of Sandy’s Northeast US landfall, we’re going to use the ERA5 database to take a look at the meteorological journey the storm that came to be known as Sandy took.

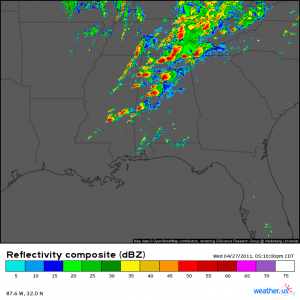

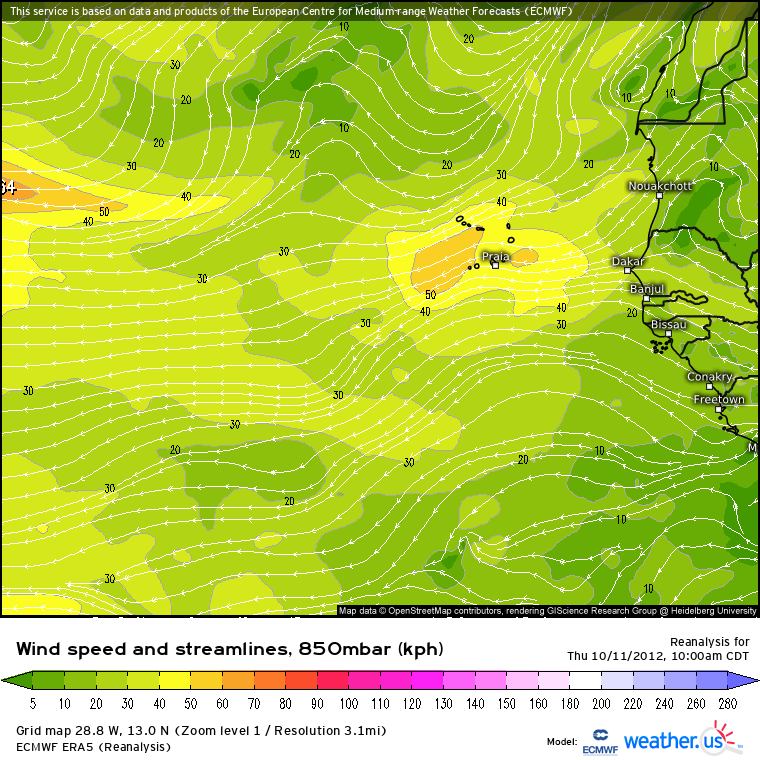

Sandy began as an African Easterly Wave that emerged into the Atlantic Ocean around October 11, 2012. Strong shear and interaction with another disturbance kept it disorganized initially.

Roughly a week later, the disturbance entered the Caribbean. The environment was initially hostile to development due to shear, but as the environment became a bit more conducive, the disturbance was able to steadily organize as it moved toward the Central Caribbean.

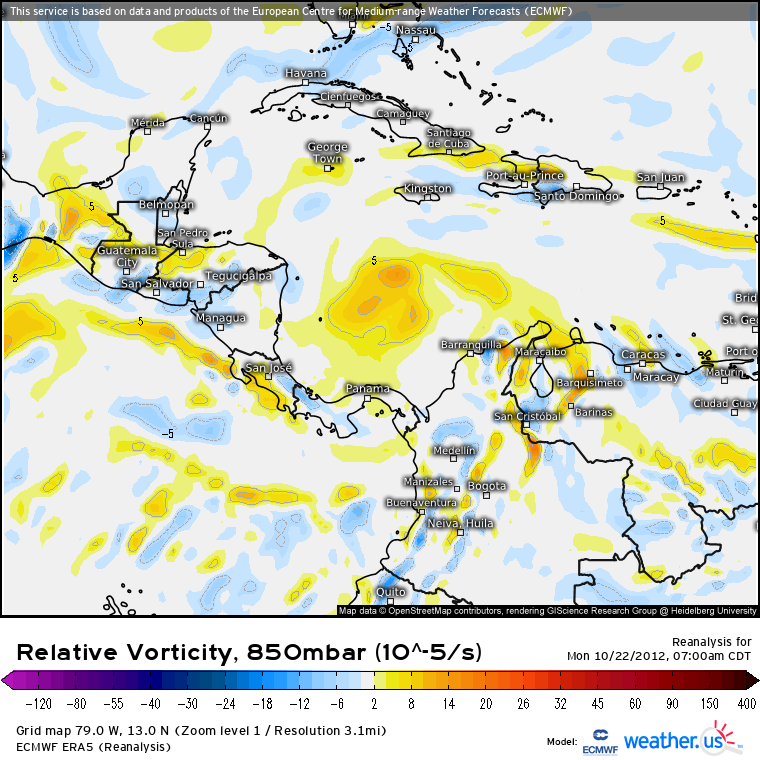

By October 22, the disturbance, positioned SSW of Jamaica, had organized enough to be classified as a tropical depression. It would be upgraded to Tropical Storm Sandy just a few hours later.

Up until this point, Sandy had been moving generally west, however, that was about to change.

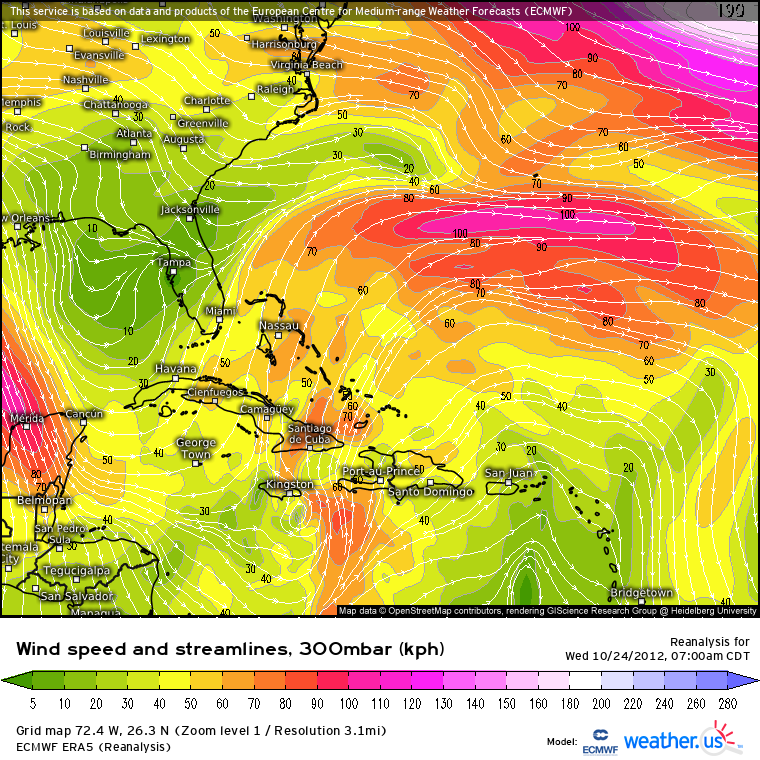

An upper-level trough dug southward over the Gulf of Mexico/the Northwestern Caribbean. This feature caused Sandy to turn sharply and begin moving north-northeastward. It strengthened as it moved, becoming a hurricane on October 24 before making its first landfall near Bull Bay, Jamaica with max sustained winds of 75 kts (86 mph).

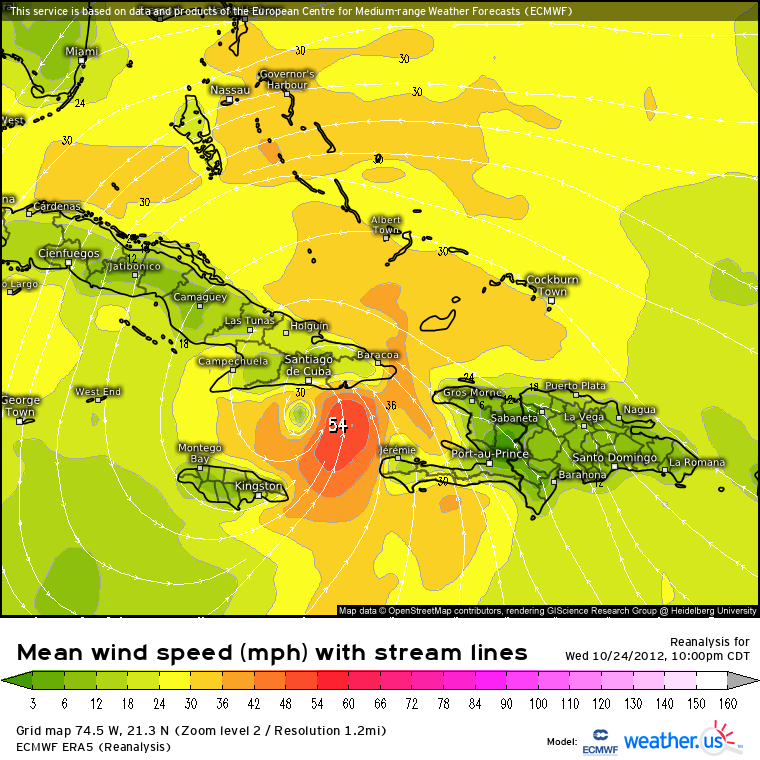

After moving quickly across Jamaica, Sandy was able to intensify further before its second landfall a few hours later near Santiago de Cuba, Cuba. Its max wind speed at time of landfall was 100 kt (115 mph).

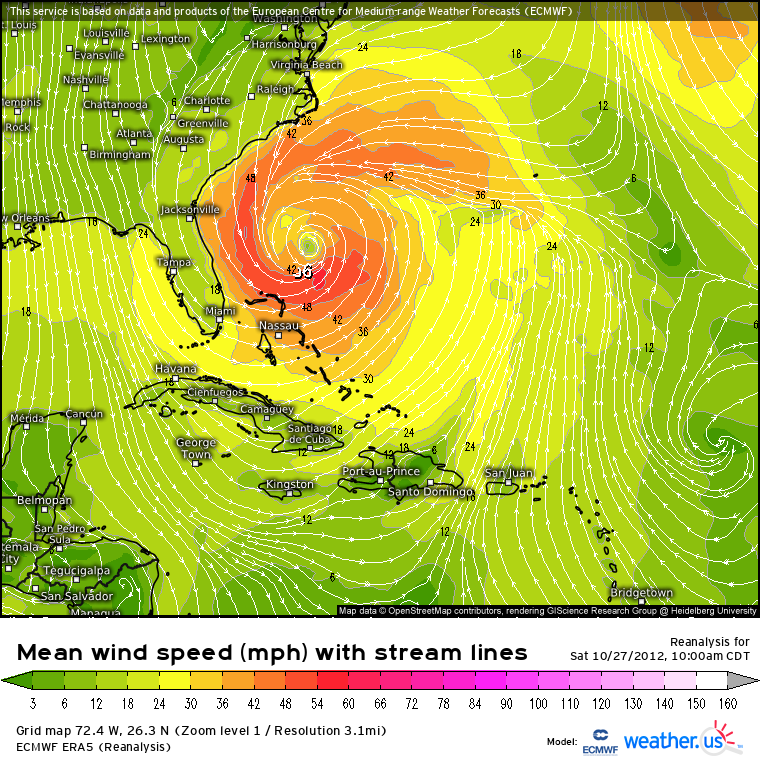

Despite a few hours over land as it crossed Cuba, Sandy emerged relatively intact. However, fairly strong shear was waiting for it, and dramatically weakened the hurricane over the next couple of days. By October 27, Sandy had dropped below hurricane status.

What Sandy lost in strength, it gained in size.

According the NHC’s official report, Sandy’s average radii of tropical-storm-force winds had doubled in size since its landfall in Cuba. The size increase was attributed to an interaction with the upper level trough that initially steered the storm northward.

Another change in direction was upon Sandy.

A trough was moving eastward over the eastern half of the US. Sandy was forced to turn northeast ahead of it. This turn allowed Sandy to skirt along the southeast coast, but far enough off shore to avoid any major impacts.

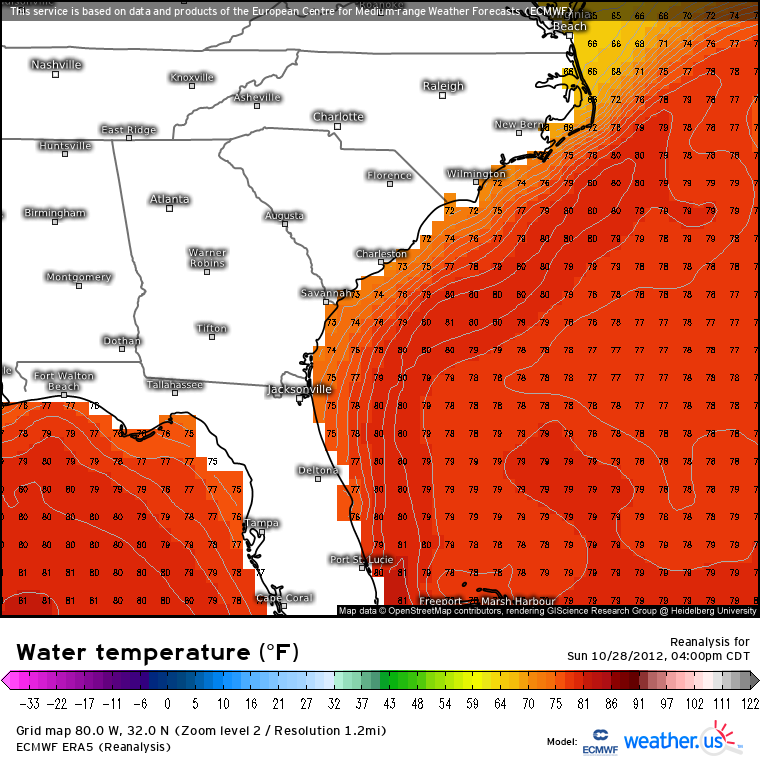

It also placed Sandy squarely over the warm waters of the Gulf Stream.

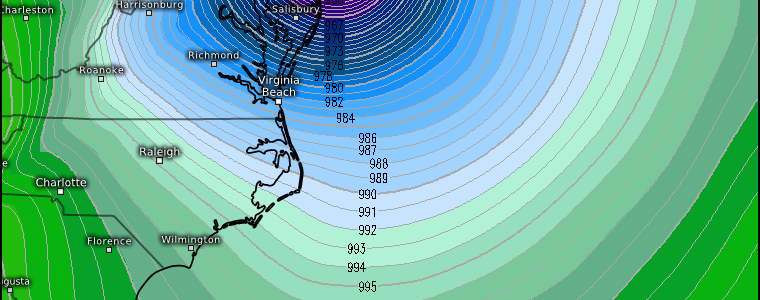

Sandy re-intensified, peaking for a second time on October 29 a couple hundred miles southeast of New Jersey. It achieved Category 2 status at this point with max sustained winds of 85 kts (97 mph).

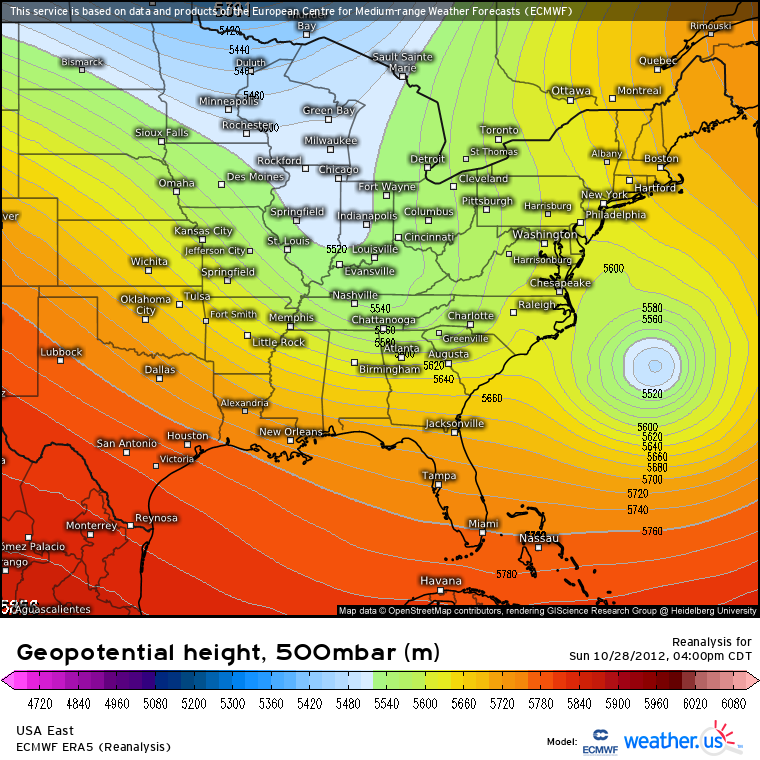

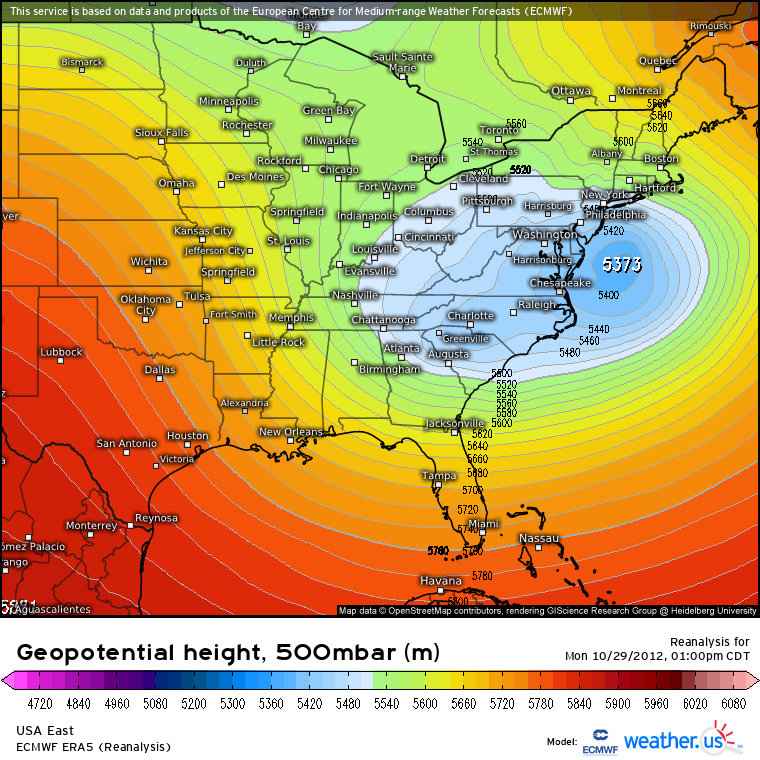

Unfortunately for the US, the trough that initially forced Sandy to accelerate northeast would now work against it.

The trough captured Sandy, pulling it in toward the coast and sealing its fate.

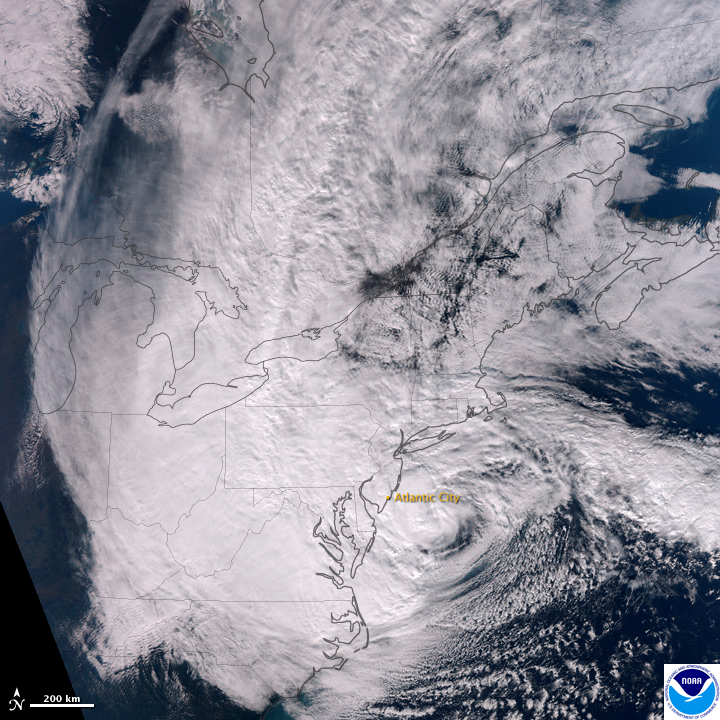

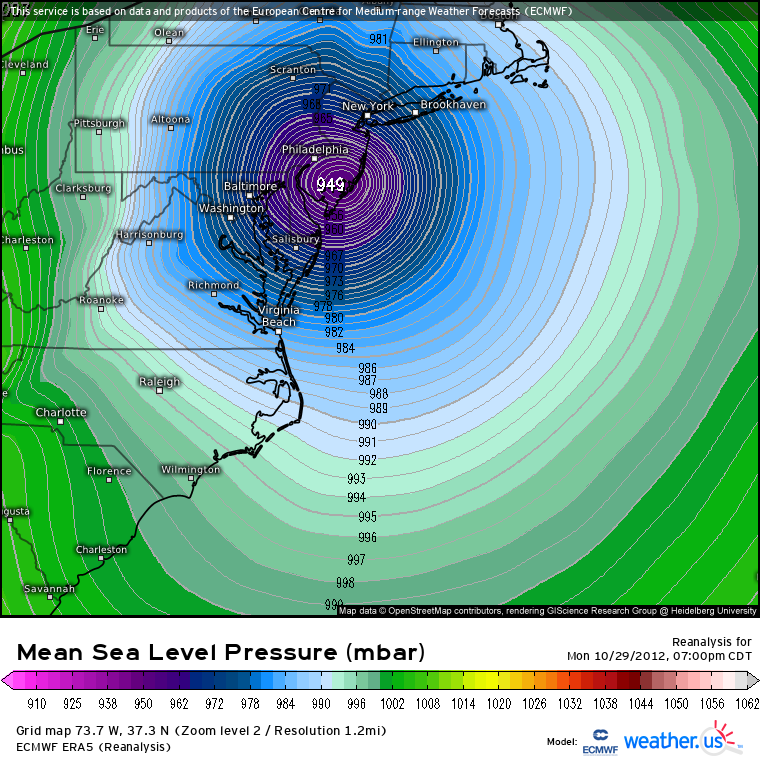

Though Sandy was technically an extratropical storm due to colder waters and interaction with the cold, continental air via the trough, it still packed a punch.

A very large Sandy made landfall near Brigantine, New Jersey on October 29, 2012. Its central pressure was 945 mb and it carried maximum sustained winds of 70 kts (80 mph).

According to the NHC’s report, peak storm surge of 12.65 ft was recorded at Kings Point, NY. Surge heights of over 9 ft were recorded on Staten Island and at the Battery in Manhattan. Sustained winds of 50+ kts were reported near/in the core with gusts approaching 80 kts.

As with all tropical cyclones (or extratropical, in this case), the impacts weren’t confined to one piece of shoreline. Since Sandy was so large, the impacts were widespread and too numerous to recount here. If you’re interested in them, I highly suggest reading through the NHC’s report found here.

If you have any personal recollections of Sandy you’d like to share, I’d love to hear them! Leave a comment below or on the post on Twitter!

***All stats and dates pulled from the official report by the NHC.