Atmospheric Fury: April 27, 2011

Frequently in meteorology, just enough atmospheric ingredients come together to make an event bad, but not devastating. Just as frequently, we experience events where a few ingredients just don’t line up correctly and are subsequently considered “busts.”

Rarely does every single ingredient fall into place perfectly to produce true devastation. But, when it does, the results haunt us for decades. April 27, 2011 was one of those times.

If the Superstorm of 1993 was the spark to my interest in meteorology, April 27, 2011 was the fire that finally drove me to pursue a greater understanding of the atmosphere.

I wasn’t yet a resident of Alabama in 2011 as I didn’t move south until 2013, but I knew many people there. I may have watched the events unfold safely from over 1000 miles away in Pennsylvania, but my then-friend, now-husband lived just south of Birmingham. His father watched the Tuscaloosa-Birmingham EF-4 pass just north of his location as he drove his mail route that afternoon.

Another friend worked in the insurance industry and was dispatched to Tuscaloosa the next day to help in clean-up and recovery. He had lived in Alabama his entire life (30 or so years at that point) and remarked to me that he had never, ever seen anything like the destruction that tornado wrought.

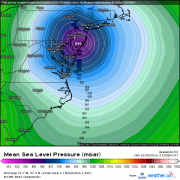

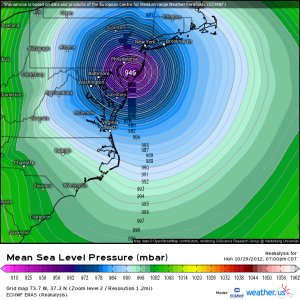

As mentioned, this outbreak was the product of every single parameter aligning perfectly to display the full fury our atmosphere is capable of.

- A negatively tilted upper-level trough dug into the central US, producing two days of severe weather in the Plains and South-Central regions before the Deep South event.

- Anomalously warm/moist conditions were advected in ahead of the system via a strong low-level jet.

- Clear skies (post morning convection) allowed for daytime heating. CAPE rocketed to values of 2000 to 3000 J/kg. Anyone who knows southern severe events knows that CAPE values this high mean business. Widespread severe weather has occurred on much less.

I’d like to pause here a moment and elaborate on something that would become important later on.

There was a preliminary round of storms that occurred in the early hours of April 27th.

Despite the time of day, this convective line was incredibly potent. It produced a few rather strong tornadoes (EF-2s and EF-3s) over Mississippi and North/Central Alabama. These tornadoes were responsible for the loss of power to many communities. They also caused the malfunction of a few NOAA transmitter sites, which lead to the loss of life-saving alerts via weather radios to the affected communities.

A potentially dangerous situation expected for later that afternoon had just become downright deadly. Without power or the ability to receive weather information or alerts, many would have absolutely no idea what was coming for them later in the day.

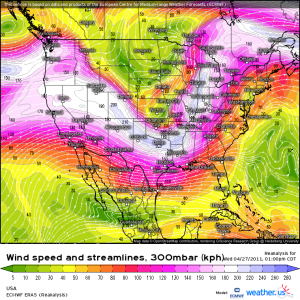

As mentioned above, after the morning storms, the skies cleared as the right exit region of a jet streak moved over the area.

For those unfamiliar with why this would matter, a little explanation: The right exit region of a jet streak is the site of convergence aloft, which translates to a sinking motion at the surface. Sinking air warms and dries, leading to clear skies.

Generally, these conditions would be counterproductive to severe weather. However, as it did on April 27th, being under the right exit region and subsequent clear skies can serve to add instability via daytime heating. This primes the atmosphere for severe weather later as the impulse moves through the region.

Those familiar with the weather and its basic workings know that clear skies before an expected severe weather outbreak aren’t a good thing. Unfortunately, to those not familiar with meteorology, the clear skies seemed to suggest that worst was over. Those without power and busy picking up the pieces from the morning storms let down their guard far, far too early.

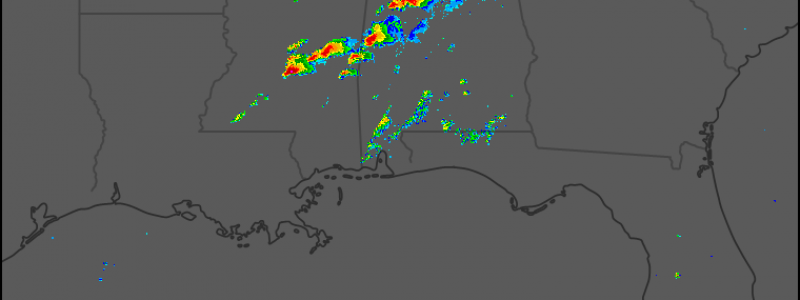

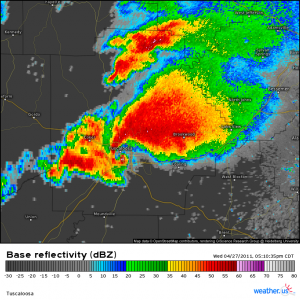

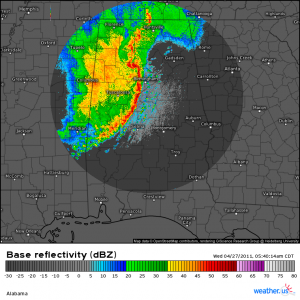

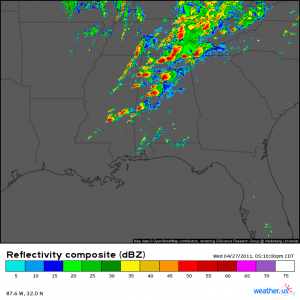

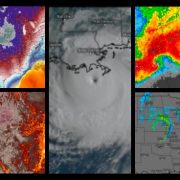

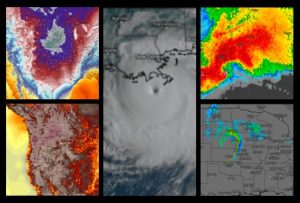

As the cold front moved eastward, supercells began to blossom, many putting down tornadoes across Mississippi. By the late afternoon, radar displayed an unthinkable sight.

Lines of supercells were visible from Central Mississippi through Alabama and into Tennessee. Many of these cells were responsible for long-track, intense tornadoes. Communities that had been hit by the morning round of storms were devastated yet again by the afternoon storms.

It was surreal. It was unbelievable. It was devastating. It was heartbreaking. It was soul-wrenching.

When the day was over, 216 confirmed tornadoes had occurred across 6 states. Six of these were long-tracked and on the ground for 60 or more miles each.

- 68 EF-0s

- 78 EF-1s

- 36 EF-2s

- 19 EF-3s

- 11 EF-4s

- 4 EF-5s

That’s the break down of the ratings for those 216 tornadoes. They were responsible for 316 deaths and more than 2,980 injured.

I don’t know about you but, even though I watched it happen live and heard first-hand accounts from friends and (now) family, these number are incomprehensible to me. My hat goes off to every single meteorologist and emergency manager that worked from before dawn to well after midnight this day to save lives. You all are heroes and saved many lives that otherwise would have been lost.

Our atmosphere is an incredible thing that can turn deadly when the ingredients line up perfectly. This day – or really, the whole 4 day event – was a terrible display of it’s capabilities. And one I hope it is never able to replicate again.

To think that one blow from mother nature can take us all out is frightening. Great content though, a super interesting read!