Could We See the Third Tropical Cyclone of the 2020 Season Form In the Gulf of Mexico Next Week?

Hello everyone!

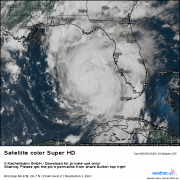

While the 2020 Atlantic Hurricane Season has not yet officially begun (that occurs on June 1st), we’ve already seen two named storms (Arthur and Bertha), and the third may be on the way next week. This post will discuss the forecast for this third system as it stands on May 28th, 2020. My goal will be to explain why conditions will be favorable for tropical cyclone development, and what to expect if a system were to develop. Overall, the threat posed to the US coastline by this system at this time is low. There’s no reason to be worried if you live along the Gulf Coast, despite scary-looking model runs that occasionally drift across social media feeds. However, the fact that tropical cyclone development is possible next week is a great reminder that hurricane season is (almost) here, and now is a great time to prepare. Even if this system ends up being a non-event (which, again, is the most likely outcome at this time), we still have five months of hurricane season left to go in 2020, and this is almost certainly not the last system we’ll be tracking in the Gulf of Mexico.

For tropical cyclone development to occur, we need five ingredients coming together at the same time and place: warm waters, low vertical wind shear, mid-level moisture, a sufficiently strong Coriolis force, and a seed disturbance. Let’s take a look at each of these ingredients to see the extent to which each will be present next week.

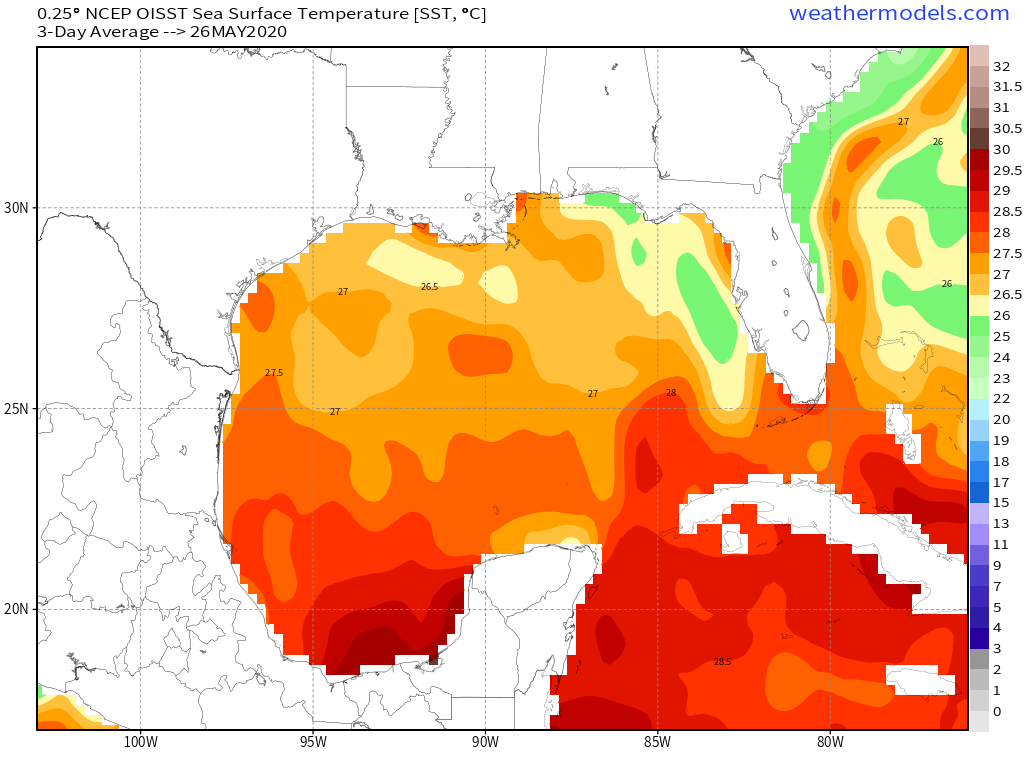

Water temperatures are probably the easiest ingredient to evaluate, and obtain in the Gulf of Mexico. To get a tropical cyclone, you generally need water temperatures greater than or equal to 26C (any region denoted by warm colors on the map above). As you can see, water temps in the Gulf of Mexico, particularly the southern Gulf of Mexico, are plenty warm (27-28C) so any developing system will have plenty of fuel.

Another “gimme” on our list is the Coriolis force which is strong enough for tropical cyclone formation anywhere north (or south) of 5 degrees latitude. The Gulf of Mexico includes latitudes from ~17N to ~30N so we’ll have no trouble getting thunderstorm clusters to spin, should such a cluster develop.

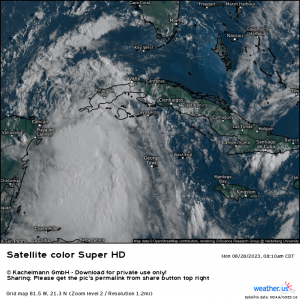

The tricky part will be getting a seed disturbance in the right place (southern Gulf of Mexico) at the right time (when vertical wind shear is low, and mid-level moisture levels are high).

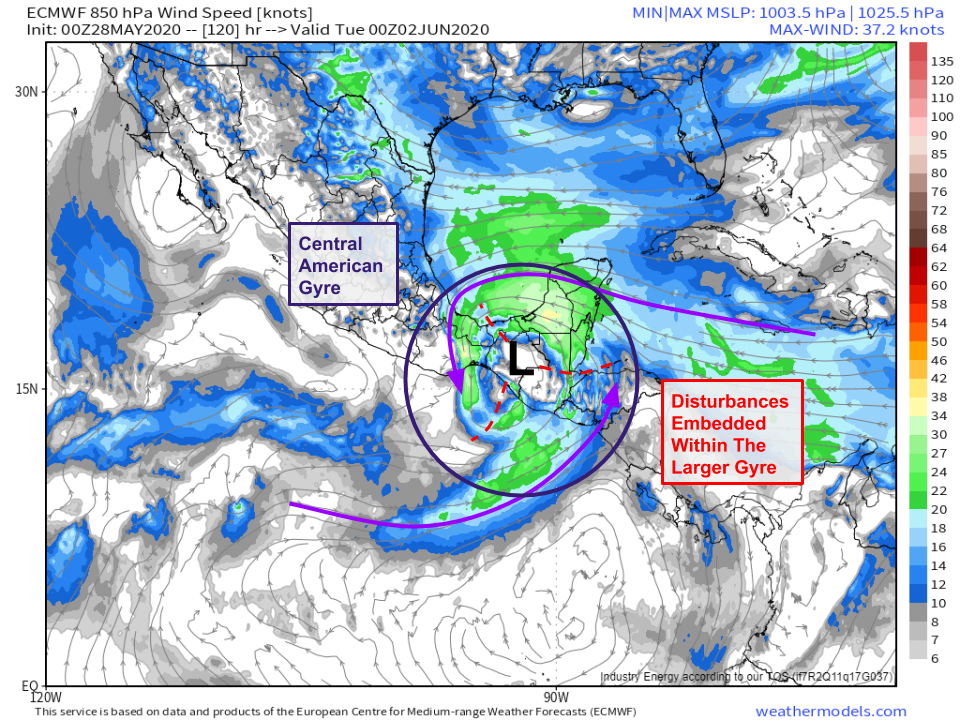

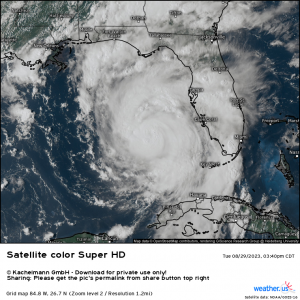

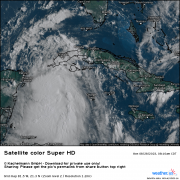

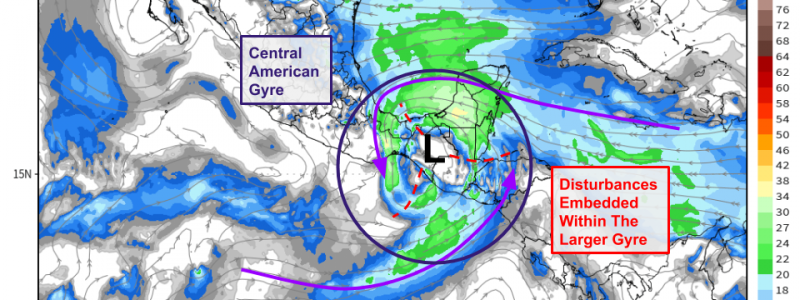

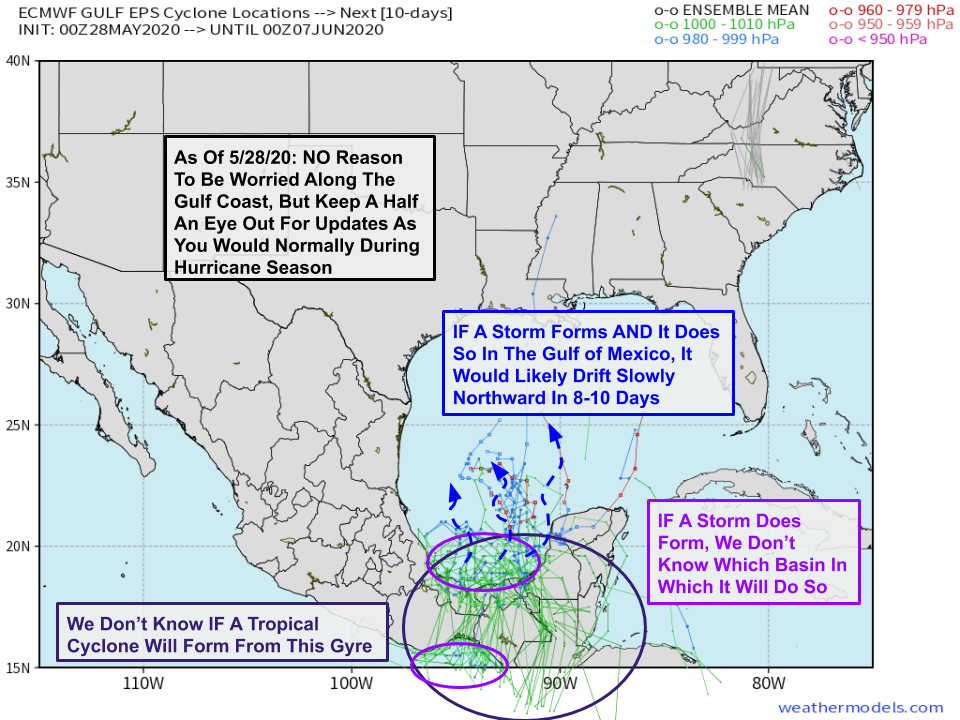

The seed disturbance we’ll be watching is a feature known as a Central American Gyre (CAG). This is a feature that forms a few times each year in southern Mexico/Guatemala/Belize/Honduras or adjacent parts of the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, and eastern Pacific. The gyre itself is too large and broad to be a tropical cyclone (by definition), or to directly produce one. However, the winds circulating around the gyre contain smaller perturbations (disturbances) which can form tropical cyclones. I’ve marked three such disturbances on the forecast map above in red. Sometimes none of these candidate disturbances are able to develop into tropical cyclones. Other times, several of them may. Usually there’s only room for one tropical cyclone per basin (at most). It’s entirely possible that the disturbance which emerges as dominant will be that which is located in the eastern Pacific. If that were the case, locally heavy rain and gusty winds could impact parts of southern Mexico and Guatemala, but there would be no impacts to the US. The scenario to watch for is that which features the development of a disturbance in the Gulf of Mexico on the northern side of the gyre.

Interested readers who have more of a background in atmospheric science will find the paper by Philippe Papin defining and discussing Central American Gyres to be a worthwhile read. If you’re shorter on time, he did an awesome twitter thread around this time in 2018 prior to another CAG event explaining what CAG’s are and how they can produce tropical cyclones.

Should a disturbance emerge in the Gulf of Mexico roughly this time next week, it would face a hostile environment for development at least initially. An upper-level trough seems likely to move into the northern Gulf of Mexico which would impart substantial northwesterly shear on any developing cyclone. However, as that trough weakens and drifts southwestward under an upper-level ridge building over the Rockies, a window of more favorable shear conditions could present itself by day 9-10. However, that’s so far out that confidence in any particular evolution (favorable or otherwise for tropical cyclone development) is quite low.

Here’s a quick animation of 500mb ensemble forecasts from the EPS showing considerable uncertainty regarding the position and intensity of the ridge over the southern Rockies and trough over the northern Gulf of Mexico later next week. The exact evolution of each of those features will decide how favorable (or unfavorable) conditions in the Gulf will be for tropical cyclogenesis.

A similar story is noted in mid-level moisture forecasts. The gyre itself will have plenty of moisture associated with it, but the trough over the northern Gulf and its associated north/northwesterly flow from the deserts of northern Mexico will be quite dry. To what extent any disturbance that emerges from the gyre will be able to develop will be strongly dependent on the strength of dry air intrusions on the system’s northern/northwestern side.

A similar story is noted in mid-level moisture forecasts. The gyre itself will have plenty of moisture associated with it, but the trough over the northern Gulf and its associated north/northwesterly flow from the deserts of northern Mexico will be quite dry. To what extent any disturbance that emerges from the gyre will be able to develop will be strongly dependent on the strength of dry air intrusions on the system’s northern/northwestern side.

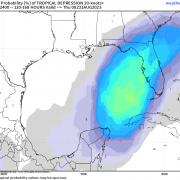

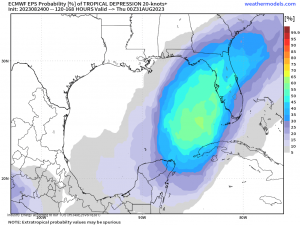

What do ensembles have to say about the odds of development? Roughly half of EPS members develop some sort of tropical cyclone in the southern Gulf of Mexico next week. Most of those are tropical depressions or weak tropical storms that will have little impact if they hit land. A minority of the members that develop this system into a tropical cyclone suggest that it will intensify enough to become a more concerning system.

For those who find the annotated spaghetti plots helpful for visualizing forecast uncertainty surrounding tropical systems, here’s a version of that analysis for this system. We don’t know if a tropical cyclone will form, and even if one does, we don’t know if it will form in the eastern Pacific or in the southern Gulf of Mexico. If a storm forms in the southern Gulf of Mexico, most ensemble guidance suggests that it will drift slowly to the north starting around 8-10 days from now. That’s all we know as of now.

For those who find the annotated spaghetti plots helpful for visualizing forecast uncertainty surrounding tropical systems, here’s a version of that analysis for this system. We don’t know if a tropical cyclone will form, and even if one does, we don’t know if it will form in the eastern Pacific or in the southern Gulf of Mexico. If a storm forms in the southern Gulf of Mexico, most ensemble guidance suggests that it will drift slowly to the north starting around 8-10 days from now. That’s all we know as of now.

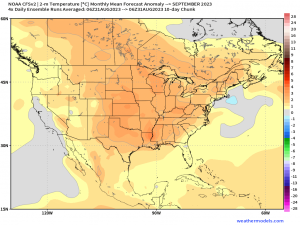

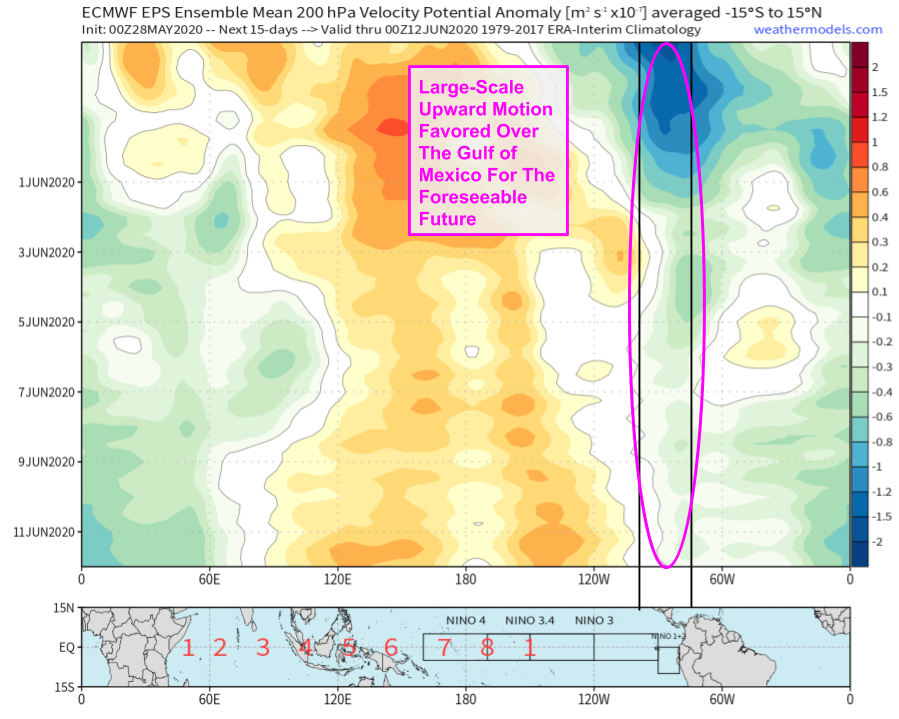

So why even mention this system? One reason is that the overall pattern on a hemispheric scale will be favorable for tropical cyclone development in the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic starting now and continuing through the first part of June.

EPS ensemble mean velocity potential anomaly forecasts are one really good way of showing this large-scale tendency towards upward motion in the atmosphere over the Gulf of Mexico starting now and continuing into June. So while it’s unclear if any particular disturbance will develop into a tropical cyclone, the odds of development are much higher than usual heading into June.

EPS ensemble mean velocity potential anomaly forecasts are one really good way of showing this large-scale tendency towards upward motion in the atmosphere over the Gulf of Mexico starting now and continuing into June. So while it’s unclear if any particular disturbance will develop into a tropical cyclone, the odds of development are much higher than usual heading into June.

Another reason is that any time a tropical cyclone is possible (and even many times where a tropical cyclone is not possible), long range deterministic model guidance spits out scary-looking maps showing strong hurricanes moving onshore 10+ days from now. These erroneous forecasts are then posted on social media to drum up likes, retweets, and shares. The net result is unnecessary alarm for folks who might not be as familiar with the nuances of weather models and the uncertainties inherent to prediction of tropical cyclones at extended range.

Regardless of whether this system ends up developing into a tropical cyclone, residents along the coast from Texas to Maine, and folks who live in inland parts of coastal states or coastal-adjacent states should take some time over the next week or two to review your hurricane plan, restock any supplies you might have used up during periods of stricter COVID-related quarantines, and make sure that you’re ready if a tropical cyclone approaches your area. The odds don’t favor it this week or next week (at least as of now), but a storm will come eventually, and the earlier you prepare, the better off you’ll be.

I’ll have more updates on this system over the coming week both here and on twitter @WeatherdotUS and @JackSillin. As always, many of the graphics used in this post are available at weathermodels.com.

-Jack