The Unassuming, Violent 12/18/1957 Tornado Outbreak

With our big weather story, a record-shattering nor’easter, clearing New England today, the CONUS is returning to a pretty quiet pattern overall. Without any pressing current events, then, I’ve decided to devote today’s blog to using the weather.us ERA5 resources to explore a fascinating tornado outbreak that began 63 years ago today, a very localized onslaught of significant and violent tornadoes.

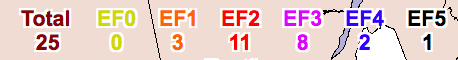

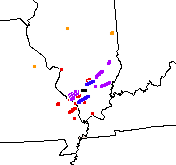

It’s hard to think of many tornado outbreaks that are more unusual than the one that struck the central US from the 17th to the 19th of December 1957. It is common to go entire winter seasons without a single tornado rated E/F3 or stronger north of the Gulf coast states, but on 12/18/57 alone, there were 8 F3s, 2 F4s, and an F5 all within a few counties of southern Illinois!

Images from NOAA’s Storm Prediction Center Violent Tornado webpage

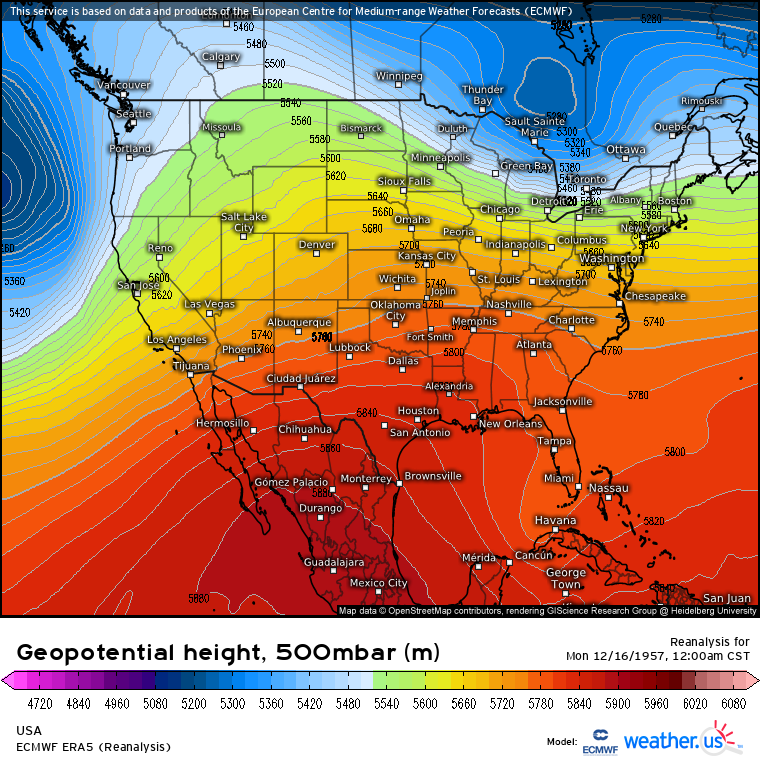

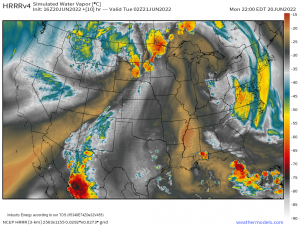

As is typical with winter tornado outbreaks, especially ones so prolific so far north, the biggest uphill battle was advecting in enough moisture to get the kind of instability sufficient for surface based convection. Often, as was the case on 12/18/1957, the culprit was not a single eager Gulf advection event but rather persistent ridging and southerly flow over the span of days. This came about as powerful, slow moving west coast troughing kept a ridge in place over much of the central US for the days before the outbreak.

This jet pattern allowed unceasing southerly flow to develop from the 14th onward over southern Illinois, which slowly but surely allowed an unseasonably moist airmass to build over the area. When a powerful shortwave split off of the impressive Pacific closed low, then, the groundwork was laid in the airmass ahead for a significant moisture return event.

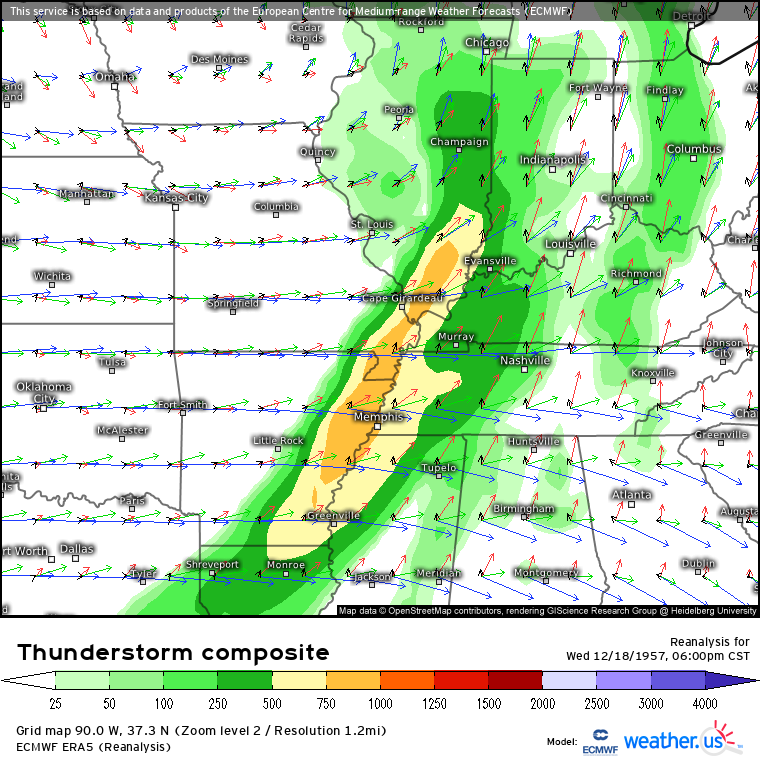

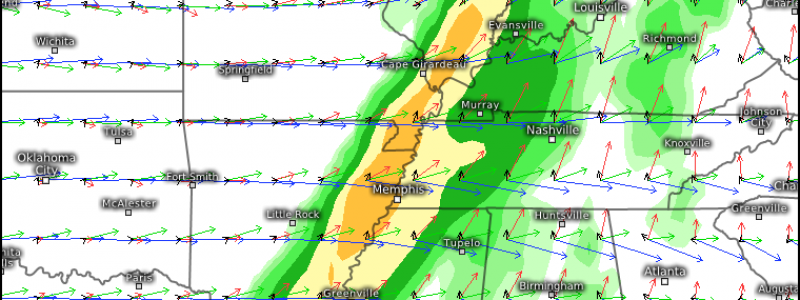

As the shortwave dug towards the east, three things happened that would prove crucial for the developing tornado threat. First, powerful 500mb flow exceeding 60 knots overspread much of the central plains, promoting deep layer shear sufficient for storm organization. Second, a strengthening 700mb jet pointed from the south-central US into the Ohio Valley was likely able to pull something of a modified EML into the region, bolstering instability. And third, as the trough axis moved into the central US, divergence immediately ahead of it allowed a low level cyclone to begin to quickly deepen. A powerful ridge pivoting through the northeast allowed a significant pressure gradient to develop over the Ohio Valley and eastern Midwest, with corresponding southerly flow increasing dramatically through noon on the 18th.

This low level jet enabled the aforementioned moisture return, several days in the making, to concentrate in a ridge of high dewpoints to the south and west of the cyclone. It also bathed the region is the type of brisk low level wind field that often fosters significant helicity.

This all meant that, by the early afternoon of 12/18/1957, significantly unseasonable dewpoints were pivoting into the southern midwest beneath a likely partially modified EML, a roaring southerly LLJ, and powerful westerly flow aloft. If upper air soundings were taken with any sort of regularity in 1957, we would likely see a profile below ~700mb characterized by very moist air straight from the Gulf, with a low LCL and LFC. Around 700mb, we would perhaps see a weak thermal inversion coincident with a dramatic dewpoint depression at the hands of our probable partially modified SW-ern EML airmass, with strong temperature drops with height through 500mb. Kinematically, a widely curved hodograph, especially in the low levels, at the hands of roaring SW flow beneath brisk midlevel wind would likely be traced. The former would likely present sufficient CAPE for surface based convection, with the latter almost certainly supportive of rotating, discrete storms. Overall, a very good environment for severe weather, especially from December, all surmised from ERA5!

Anyway, the predictable result of a cold front moving through an environment like this is a severe thunderstorm outbreak for sure, but parameters were certainly not as good as those typically associated with two F4s and an F5! This is where the reality that synoptic conditions can only explain so much comes in. Some events with multiple violent tornadoes, like this year’s Easter Sunday outbreak or, for a more extreme example, the 2o11 superoutbreak, have synoptic setups that jump off the page. The good, but in no apparent ways exceptional, large-scale parameters of 12/18/1957 only go so far in explaining the violence of that day. This is not overwhelmingly surprising for such a localized outbreak, but it’s still a fascinating puzzle for meteorologists to figure out. We’ve gone far today, even if we couldn’t go all the way.