The Atlantic is Stirring. Will it Soon Awaken?

What if I told you there’s a climatological indicator on the sub-seasonal scale associated with a huge increase in hurricane frequency, intensity, and societal impact? That it almost always coexists with many of the of the atmospheric conditions most favorable for tropical cyclone development and intensity- low wind shear, high oceanic heat, high environmental moisture? Furthermore, that the occurrence of this indicator is so easy to predict I could do it without even using forecast models?

The indicator is named after an ancient Roman emperor, a leader of an empire that was able to measure and predict it with fairly primitive tools and lackluster atmospheric understanding. Admittedly, they did not draw up its connection with Atlantic hurricanes, although that discovery also likely predated even Franklin’s weather observations.

Crazy, right? Now, what if I told you we’re actually a week into the occurrence of this sub-seasonal indicator?

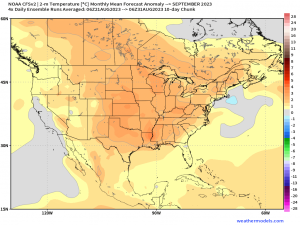

If you haven’t figured it out by now, I’m referring to the month of August. As the dog days of summer are met with bathtub SSTs, increasing mid-atmospheric monsoonal moisture from Africa, and the increasing retreat and weakening of shear-producing extratropical systems, sporadic and weak tropical cyclones are rapidly replaced with numerous, intense hurricanes. It’s a pattern that repeats year after year, earning the delineation of ‘climatological peak’ hurricane season. And, after a pretty extended lull in tropical development since July’s Elsa, the increasingly favorable oceanic and atmospheric conditions seem intent on shaking some life into the basin.

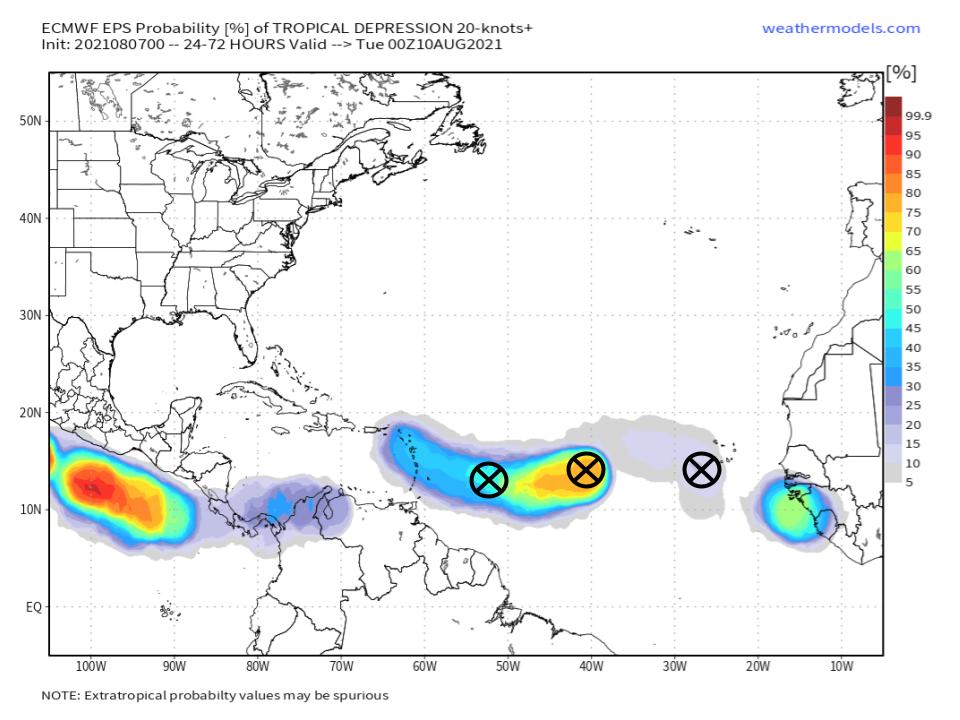

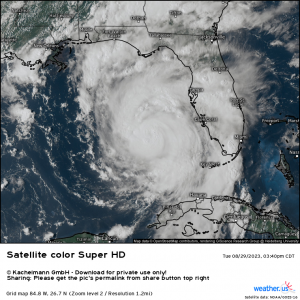

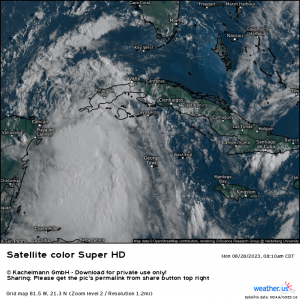

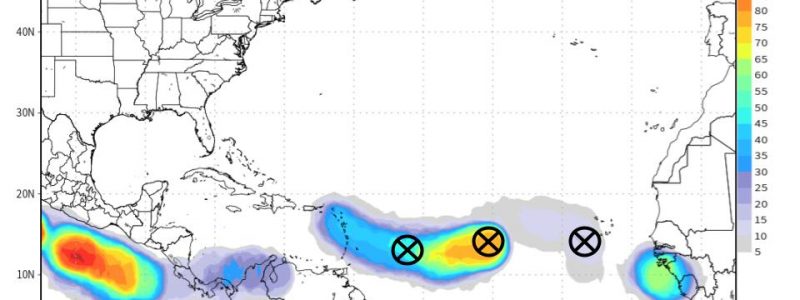

Currently, the Hurricane Center is tracking three ‘invests’, or storms as of yet too immature to be delineated as tropical depressions.

They exist within a particularly moist envelope known as the monsoon trough, which often seeds invests as it drifts off the African coast.

Favorability often abounds for the type of system that can develop out of the African monsoon trough. The enhanced moisture within the trough is favorable for convective organization, there’s a lot of warm ocean between Africa and the Greater Antilles, and shear-inducing midlevel flow maxima are usually few and far between. Adding those factors to the tendency for Cabo Verde storms that don’t curve north to impact North America helps show why atmospheric scientists watch these types of storm like a hawk.

With systems so weak and diffuse, so prone to dramatic changes in track and intensity from small atmospheric shifts, it can be difficult to forecast strength and motion more than a day out. That won’t stop me from trying, though.

A midlevel ridge sandwiched in the central Atlantic, a common fixture for this time of year, will gently push the two easternmost invests almost due east for the near term, where they will interact near the front edge of a moisture envelope which should prove supportive as long as westerly shear remains in check. Almost certainly, at least one of these invests will never close up. If the other fares better, it will absorb the one that couldn’t make it. With a little more room for error against dry air, more model support, and greater distance from shear, I imagine the middle invest will have the best shot at developing further, and could absorb the one in front. It’s frankly fairly hard to tell from guidance, though, and it doesn’t matter all that much. Meanwhile, the back invest will see drier air and stronger, easterly shear, which will probably keep it from ever closing off.

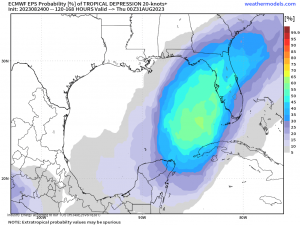

The solution modeled by the ECMWF is fairly reasonable- one of the first two invests closes into a depression, while the other one nearby does not, and the one closest to Africa dissipates. The one that closes will probably round the southwest section of the large North Atlantic ridge, the strongest steering current in the fairly weak flow regime dominating the central Atlantic.

Luckily for land interests, shear will dramatically increase with proximity to the Bahamas. Even if an invest makes it to becoming a depression, then, it’ll face almost assured disruption before it can be too impactful. Still, there’s a fairly significant possibility of a period of heavy rain over parts of the Caribbean associated with whatever becomes of the invest, or perhaps its skeleton.

Lastly, some of you may have seen the GFS, which develops one of the invests into a hurricane over the SW Atlantic before pulling it north, a few hundred miles east of the US coast. This is improbable, but does demonstrate the likely decrease of shear with eastward extent next week, which could promote a stronger storm if the invest’s future track ends up over open water. But, considering this contingency would reduce the impacts to a bunch of fish, there isn’t much reason to worry yet. Stay tuned, though, and if you haven’t yet, make a hurricane plan for the season!