Storm Brings Strong Winds, Precipitation to West Coast

A relatively calm November weather pattern will exist today across the United States. This is because a giant ridge is pushing our troublesome trough out to sea over the east coast, which means almost all of the favorable divergence for low-level cyclone development, and corresponding unsettled weather, is moving into the central Atlantic. Instead, much of the US is seeing convergent flow aloft at the moment, which corresponds with surface pressure rises.

There is one exception, though. A powerful ball of cold midlevel air is currently spinning into the Pacific Northwest, and with it comes the most intense west coast storm system yet this season.

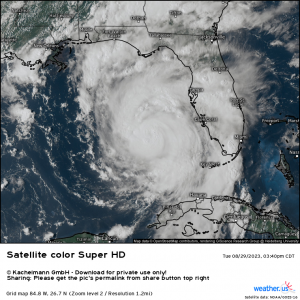

Notice the notch of midlevel low pressure rotating into the British Columbian coast through hour 24 in the loop above. This compact shortwave corresponds with an incredible environment for low-level cyclone development, leading to dramatic pressure falls at the surface. In fact, a sub-970mb low is currently moving onshore just north of the international border. Even following the shortwave’s departure, the midlevel cyclone will stick around, maintaining a presence of a few low-level low pressure centers that will spin into the Pacific Northwest coast over the next few days. This sets the scene for our discussion of sensible weather in the region.

The most significant and obvious way this intense surface low will impact the west coast will be wind! When pressure gradients point onshore in the Pacific Northwest, the unique regional topography can assist in allowing strong winds to develop. This is predominantly based on two things:

- The very long fetch of relatively frictionless ocean over which winds can build

- Mountains that are relatively exposed to higher-altitude air

This all makes intuitive sense, as wind is stronger where friction is weaker, which is over the flat ocean (and the coasts nearby) and way above the ground (and the mountains that jut into this environment).

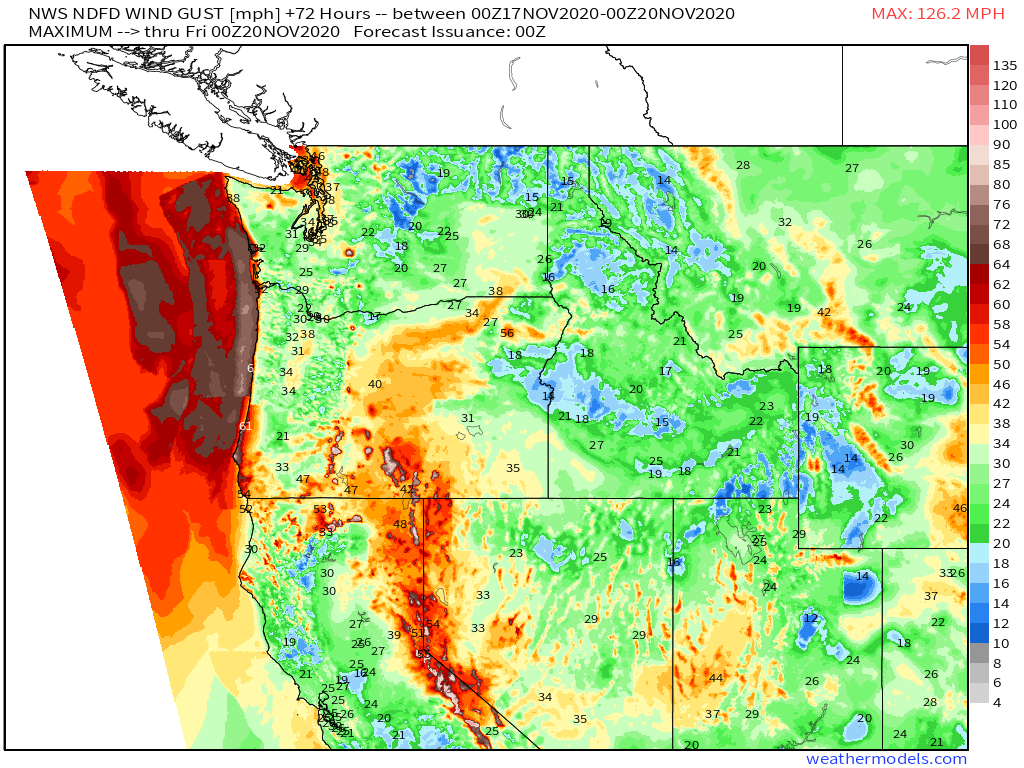

We end up with a forecast wind gust map for +72 hours that looks like this, then:

With strong but manageable winds across most of the Pacific Northwest, but roaring, potentially damaging winds at the immediate coast and at high elevations.

Wind gusts exceeding 70mph at the coast, and approaching 130mph at higher elevations, suggests something else about this system: the pressure gradient at the low levels is sufficient for ripping wind away from friction sources, and so there’s probably one heck of a jet where the friction decreases, the 850mb level.

Looking to 850mb flow confirms this hypothesis- a speedy LLJ to 65 knots currently exists along the pressure gradient south of the low-level cyclone, along the Pacific coast. Flow to 35 knots exists even further south, near the OR/CA border, and this speed max will continue moving southward as a more impressive pressure gradient rotates towards the California coast tomorrow. The flow will then weaken, and move back north into the deeper Pac NW.

Persistent low level flow off the west coast screams one of my favorite weather terms: atmospheric river! The powerful jet will advect moist air towards the coast as long as it has adequate strength and westerly component. And because the slow-to-dissipate low level cyclone looks to maintain an onshore pressure gradient over the Pac NW through the next 48 hours, there’s reason to suspect a degree of moisture transport towards the coast. To confirm, let’s look at integrated vapor transport, a metric of moisture-laden low level flow.

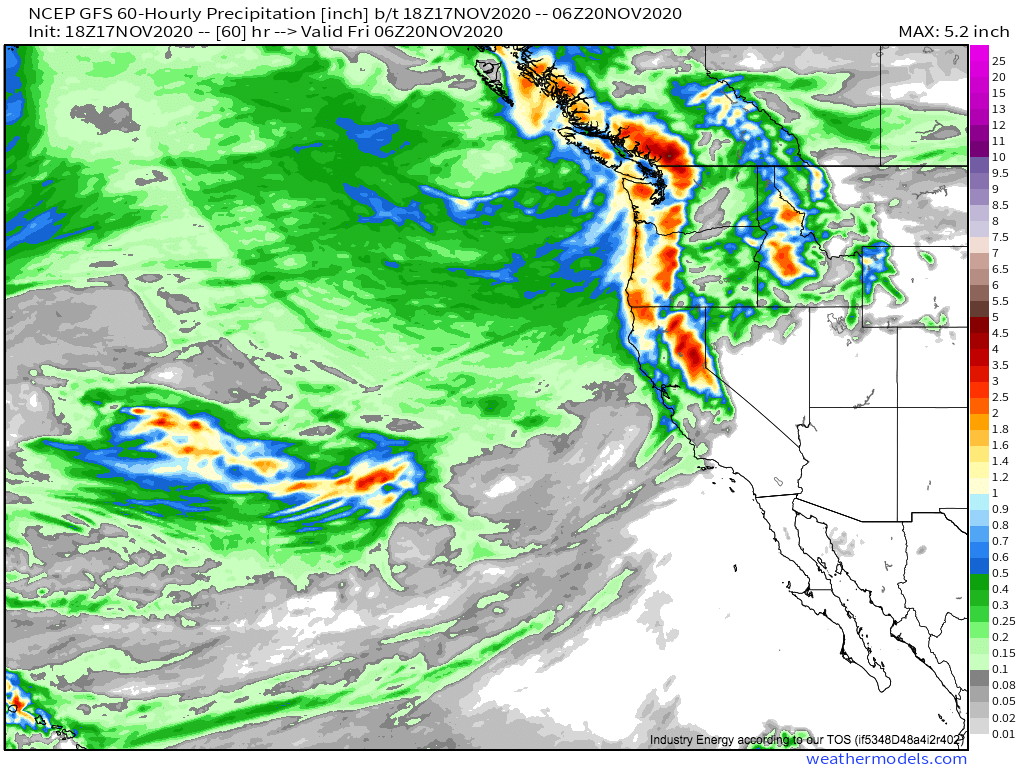

As expected, the low level jet will hose the northern half of the west coast with persistent moisture, indicated by moderate to high IVT values.

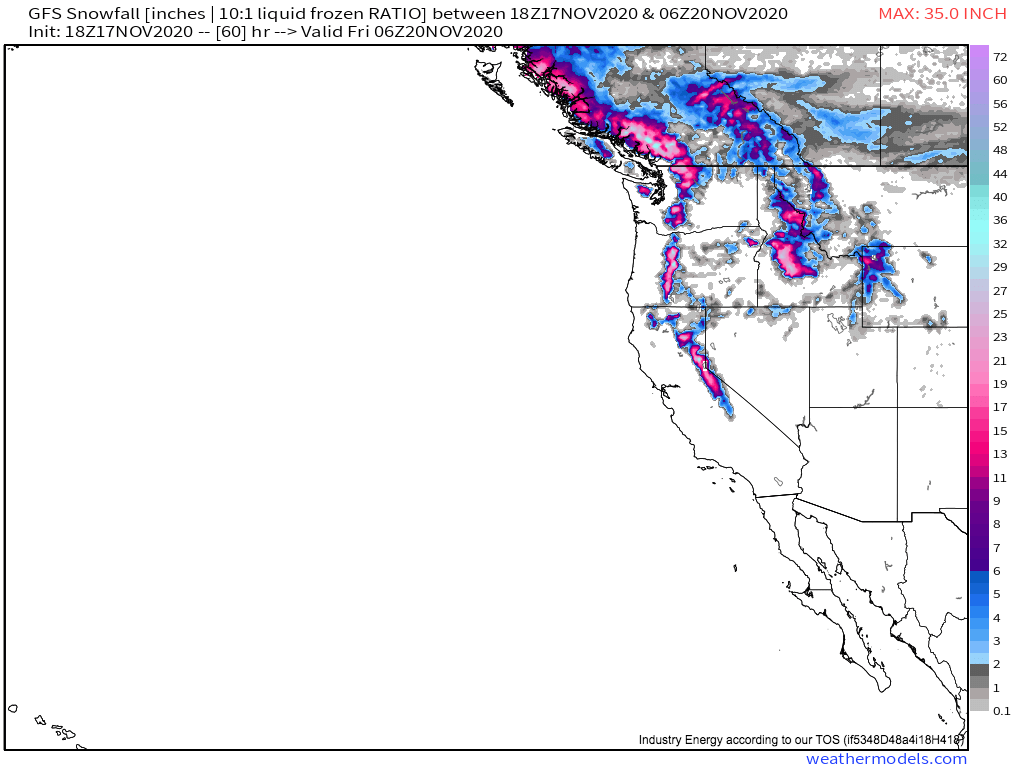

This will translate pretty directly to sensible weather. The rapid increase in friction as low-level flow smacks the coast will create a form of convergence common in, say, lake effect snow that should lift parcels to condensation, allowing this moist flow to drop rain as long as it sticks around. Over the mountains, where upsloping creates more intense, long-lasting lift, precipitation in the form of rain and snow will be common with the persistent onshore jet. Close to the Canadian border, where the pressure gradient will be very slow to slacken even as flow becomes more zonal, very persistent moisture transport will lead to somewhat substantive precipitation accumulations. Further south, where the atmospheric hose will only be on for around 24 hours through tomorrow, lower but still notable amounts are likely. In both of these zones, higher topography, where upsloping means lift will be more significant, locally higher accumulations are likely. In the Sierra Nevadas and other areas of high terrain, much of this will even fall as snow.

As a deep midlevel cyclone slowly winds down over the Pacific Northwest, strong winds will give way to a long fused precipitation event at the hands of persistent onshore flow. Much of the region will see precipitation, with substantive rainfall possible in favored topography, especially close to the Canadian border. In the mountains, a couple feet of snow are possible.