Severe Threat Continues Into Mid-Atlantic

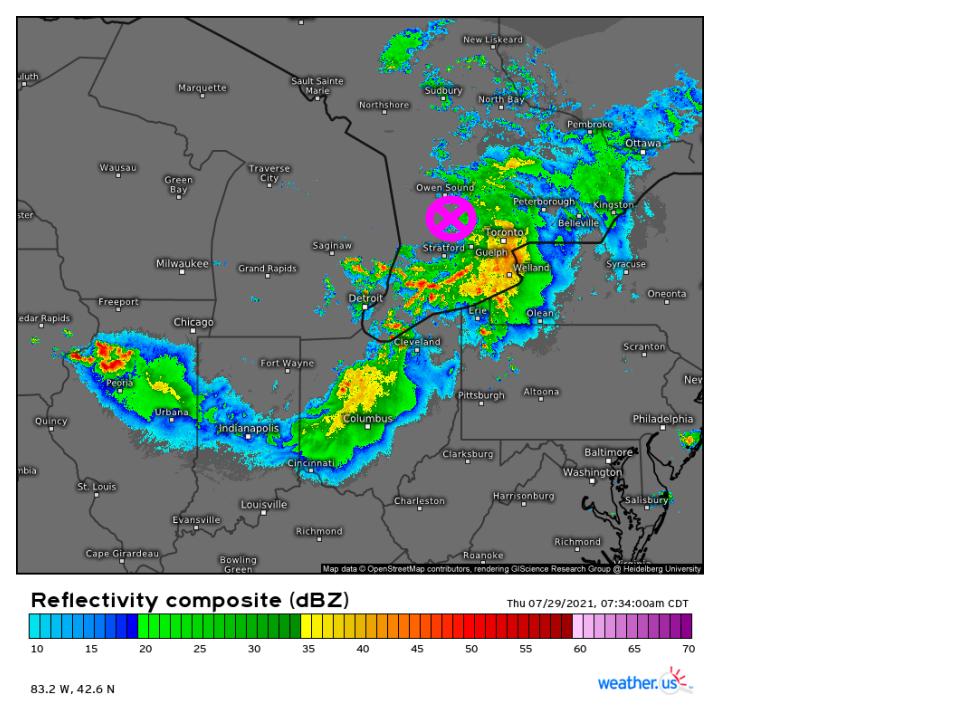

Last night was quite the active night for severe weather, as a strong mesoscale convective system roared through parts of the Great Lakes. Whether it ends up classified as a derecho or not still remains to be seen, but it certainly produced widespread damaging wind, with substantial gusts occurring in parts of Wisconsin.

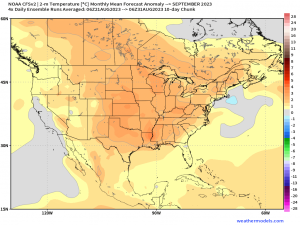

I discussed in my Tuesday blog how the northern periphery of a so-called ‘death ridge’ can support significant severe weather. Today, severe thunderstorms are once again likely along this ‘ring of fire’, southeast of where the threat was concentrated yesterday.

Strong thunderstorm complexes can develop their own mesoscale low pressure systems, appropriately known as mesoscale convective vortices (MCVs). Surface analysis suggests that one developed with overnight convection, and is currently centered over far southern Ontario.

Like a synoptic low, MCVs often have features similar to warm fronts and cold fronts, and typically engage in some degree of feedback with winds aloft. In this case, maximized winds through the 500mb level associated with the rear inflow jet from last night’s convection now coincide with a ‘cold front’ trailing through Ohio, and will serve important in enhancing helicity and organization in any storms that should develop along it today as it progresses east into the mid-Atlantic. Note, the ‘cold front’ is actually serving as something of a moist front here, with relatively rich dewpoints behind it, and not much of a temperature gradient across it. But, like a real cold front, it drapes south of the low and will serve to force wind to converge, promoting the type of lift that can work with CAPE to produce vigorous updrafts. From here, I’ll be referring to it as the MCV convergent front.

Widespread convection has largely degraded the elevated mixed layer (EML) that rode atop the ‘death ridge’. This layer can give midlevel lapse rates a huge boost, helping dial up CAPE to the sky-high values that parts of the midwest were dealing with yesterday. Remnants of the airmass will help pull MLRs to perhaps 6.5ºC/km, a solidly ‘average’ value that will neither encourage nor discourage vigorous thunderstorms.

Looking at the rest of what makes for energetic thunderstorms, we must also consider moisture content. Relatively marginal dewpoints in place over the Appalachians will keep the most substantial moisture limited to the region between the mountain chain and the Atlantic coast. Meanwhile, a northern extent of this moisture field will lie with cooler temperatures under the influence of showers and thunderstorm outflow tied to the MCV’s ‘warm front’. Unlike the MCV convergent front, the MCV warm front will actually act like a warm front.

This gives us an area of concern, then, as enhanced flow aloft that will coincide with mesoscale convergence moves into a solid area of moderate instability.

The fairly diffuse MCV warm front will focus convection for much of the afternoon, with moderate bulk shear at the hands of an enhanced 500mb jet encouraging storm organization. Piggybacking off of last night’s rear inflow jet, remnant strong flow in the low levels will enhance helicity, especially just south of the front. This will open the door for sloppy, high-precipitation supercells imbedded within what should be fairly widespread convection and stratiform rain. A couple tornadoes will be possible, alongside scattered to widespread wet microbursts capable of damaging wind gusts. Additional, more discrete storms should develop along the MCV convergent front with time, continuing a risk for scattered wind damage and isolated tornadoes.