Second Severe Season On The Horizon?

Ah, Fall. Falling leaves, pretty colors, pumpkin patches, cooler temperatures, and the return of widespread severe weather threats. Yup, you read that correctly.

As you may or may not know, a “second severe season” exists for the US – mainly in November and December. Unlike Spring where increasing warmth combined with the polar jet still dipping fairly far southward drives the threat, the Fall severe season is a combination of the increasingly southward migration of the polar jet combined with warmth that hasn’t quite abandoned the more southern reaches of the US. So, as the number of powerful fronts driven by large temperature gradients increases, so does the potential for more large-scale severe threats.

Which is what we’ll see toward the middle of this week.

Before anyone starts panicking, this particular severe threat, though it covers a large area, does not seem to be particularly potent. Let’s look at why.

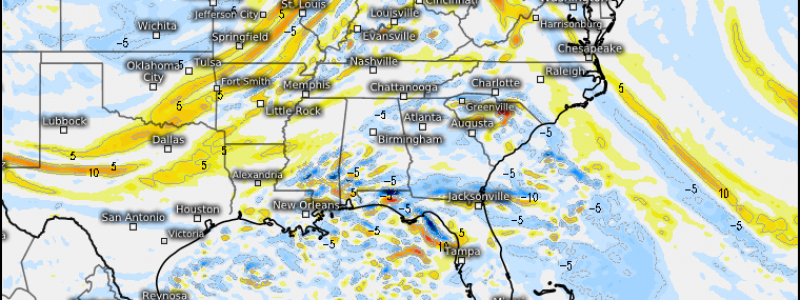

As a trough dips into the Northern US, a shortwave pivoting around it will provide forcing for ascent (rising air). Take a look at how the streamlines diverge ahead of the base of the trough. We call this diffluence. When it occurs aloft (the map above is the 300 mb level), it encourages air to rise at the surface to fill the void created above.

Let’s go down a few hundred millibars and look at the 500 mb level.

At 500 mb, we look at vorticity advection. Vorticity is the amount of spin in the atmosphere – an ingredient needed for storms to form.

If we inspect this gif, we see the shortwave attached to the main trough. While we see some positive vorticity advection (good for storms), it’s not terribly strong. Generally that means that the forcing for ascent, or mechanism that makes air rise, won’t be very strong. This lends to a weaker event.

Vorticity advection increases in strength on Wednesday as the low becomes more powerful, which may lend to a slightly more promising event for the Tennessee/Ohio River Valleys.

Let’s look a bit lower.

At the 850 mb level, we’re looking for heat/moisture transport. So, ahead of mid-latitude cyclone, we want to look for the low-level jet. The source of this jet will tell us what kind of air we can expect to stream in ahead of the front.

For this event, the low-level jet strengthens decently heading into the evening hours of Tuesday. This is good for storms – more moisture, more pile-up of air meaning it will all need to rise as it converges.

However, let’s look at that jet more closely. If you’ll follow the streamlines, you’ll see it is mainly coming out of the southwest. It’s not coming directly from the Gulf to the south/southeast where the warmest, most moist air lies – at least not until later on. Instead, it’s coming from northern Mexico and Southwestern Texas. While this air is no doubt warmer and carries some moisture, is it enough?

Well, not really. Dewpoints in the upper 50s and low 60s stream as far north as Minnesota and Wisconsin, but that really isn’t a lot of moisture for storms to work with. Can it get a few thunderstorms going? Absolutely. Can it fuel a widespread, widely dangerous outbreak? Not exactly.

Slightly better moisture comes northward out of the Gulf and into the South on Wednesday, but that region is far-removed from the best forcing for ascent and likely won’t be able to take advantage of it. However, with the presence of “okay” moisture in the Tennessee/Ohio River valleys, a marginal risk of severe storms may exist here – closer to the best lift.

Let’s take a look at a few forecasted soundings.

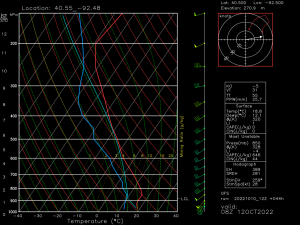

This one is for the Mid-Mississippi River valley overnight Tuesday into Wednesday.

One thing that really stands out here is a nocturnal temperature inversion. Air at the surface will be cool and stable. Any storms will be elevated. This makes the severe threat only marginal, then, as severe gusts would have to break into the stable layer to impact the surface.

Other than that, this is just an okay, not very exciting, forecasted sounding. There is hardly any directional shear to speak of as winds are nearly unidirectional out of the southwest above 900 mb. In addition, though there is decent low-level speed shear due to a strengthening low-level jet, winds aloft don’t really lend to the type of shear we would need to see supercells organize.

This will likely lend to a broken line/linear mode that may or may not contain some threat of damaging winds.

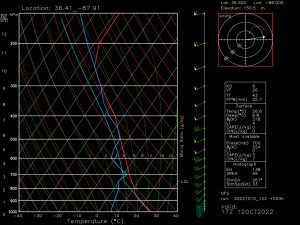

Wednesday’s threat across the Mid-Mississippi/Tennessee/Ohio River valleys looks slightly more promising – but only slightly.

We’re still expecting to deal with sub-par speed and directional shear, but steep low-level lapse rates and dry lower-level conditions could serve to enhance the damaging wind threat. Once again, we’ll be dealing with a linear/broken line storm mode with damaging winds potentially embedded in the line.

As I mentioned in the beginning of this blog, this isn’t a huge severe threat. At best it is a widely-scattered damaging wind event. But, it does serve to remind us that Fall is not all about cooler, calmer weather. We need to remember second severe season and be ready in the event that the larger, more potent severe threats do materialize.