Let it Rain, Let it Rain, Let it Rain!

It was a dry season nearly without precedent.

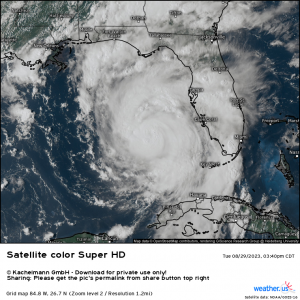

Following two of the driest ‘wet’ seasons in regional memory, the West’s six-month summer has been exceptionally hard, marred by extreme heat, explosive wildfires, and depleted reservoirs. At present, it can be hard to comprehend the amount of water needed to dig the Western US out of an extraordinary drought. Certainly, such rain is not something that can accumulate on small timescales. Rather, the West will need a months-long onslaught of atmospheric river events, each dropping prolific precipitation in the coastal hills and interior mountains of the region.

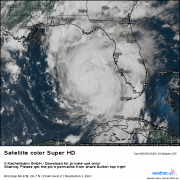

But now, with a major coastal storm on the horizon, it is once again time to revel in water while forecasting for a wet season that could prove extremely consequential.

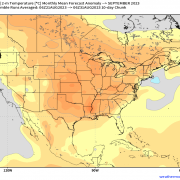

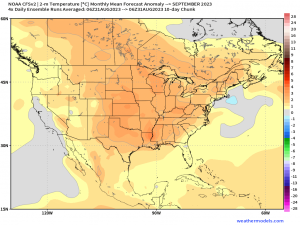

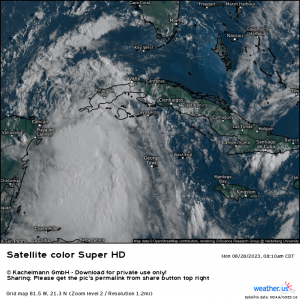

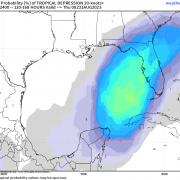

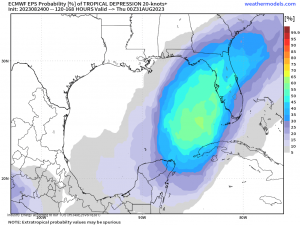

Medium range ensemble guidance depicts a fairly unusual midlevel evolution over the next couple weeks, as an anomalous midlevel trough remains static over the Pacific, wedged west of a powerful Hudson Bay ridge.

The result will be a largely unwavering divergent regime aloft over the Pacific coast of the US, which will enforce multiple, long-duration periods of mass removal. As air is evacuated from the low levels, long fetches of poleward flow drawn from the tropical Pacific will begin snaking towards the west coast.

These periodic low level jets will smash into the coast in fairly rapid succession over the coming weeks.

The long strands of southwesterly flow plunging towards the Pacific coast will carry with them the airmass at their source, which for the tropical ocean is laden with water vapor. As this vapor is sucked ashore by the LLJ filaments, it crashes into mountains and coastal friction. Both force convergence, turning the conveyer belt of deep tropical moisture into prolific rainfall.

Because neither mountains nor coastlines move very fast, and because the long strands of vapor advection move almost directly parallel to their orientation, this prolific rainfall can last a long time. Just check out how little the maximized moisture advection varies in this loop of integrated vapor transport.

The result will be a lot of rain, which will be overwhelmingly beneficial. The exception could be where very heavy rain falls in burn scars, especially from the massive Dixie fire; the hydrophobic ash and tree death will likely result in heightened risk for flash flooding and landslides that could prove locally disastrous.

But everywhere else, expect a wet season off to a good start. Hopefully, the next four months take the ball and run with it.

Ein Kommentar zum Beitrag