Ida’s Remains to Bring Northeast Substantial Flood Risk Tomorrow

An impactful chapter in the hydrological history of the Northeast could occur tomorrow as the remains of Ida interact with a slow-moving warm front over an area rendered thoroughly saturated by highly anomalous recent rainfall.

Flash flooding is the process by which excessive rainfall overwhelms the ability of its environment to remove runoff. This means it can be helpful to think of the threat as resting upon two columns: the development of a (chronic) environment incapable of safely mitigating runoff, and the development of the (acute) atmosphere capable of producing very heavy rain.

The stage setting and the show, if you will.

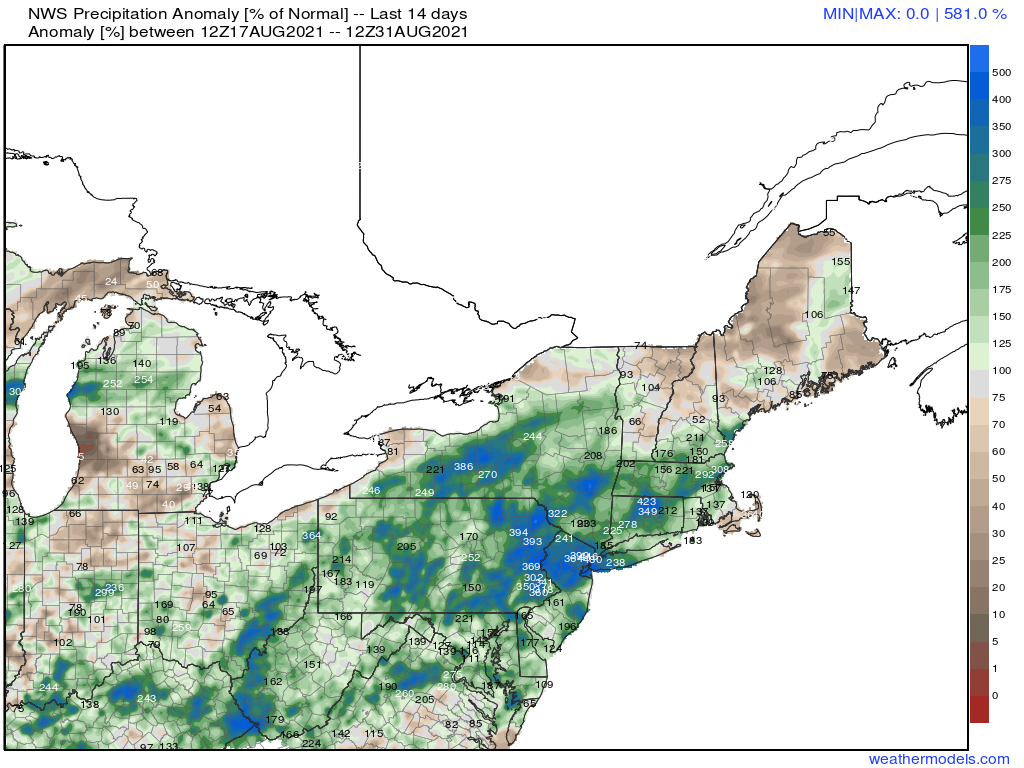

This means that tomorrow’s hazard won’t start tomorrow. Rather, it began two weeks ago, as thunderstorms training amidst a PRE supported by tropical storm Fred dumped inches of rain across West Virginia, central Pennsylvania, and south-central New York. When the body of the tropical cyclone brought extensive tropical stratiform rain to the region in the days to follow, 72 hour rainfall across much of the interior Northeast exceeded 5″, amounts that encouraged scattered flash flooding, record streamflow, and deeply saturated soils.

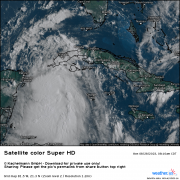

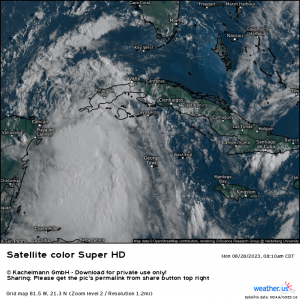

Only days later, tropical storm Henri made a slow loop over southern New England, sending a long-duration convergent band deep into eastern Pennsylvania, northern New Jersey, and southeast New York. Initial fears that the resulting 6-8″ of rain would fall where Fred had recently dropped prolific rainfall fell short as a result of the slight geographical inconsistency between storms. However, this just meant that, by the time Henri moved offshore last week, a very large swath of the northeast had seen an extreme week rainfall.

That brings us to this afternoon, as it becomes increasingly clear that Fred was not laying an environment for Henri to take advantage of. Rather, Fred and Henri were setting the stage for Ida.

The type of extreme deviation from normal precipitation that I’ve discussed encourages flash flooding by overwhelming the ability of the environment to safely whisk away rainfall, mostly through saturating the ground. This saturation can substantially decrease the amount of rain necessary to trigger flash flooding.

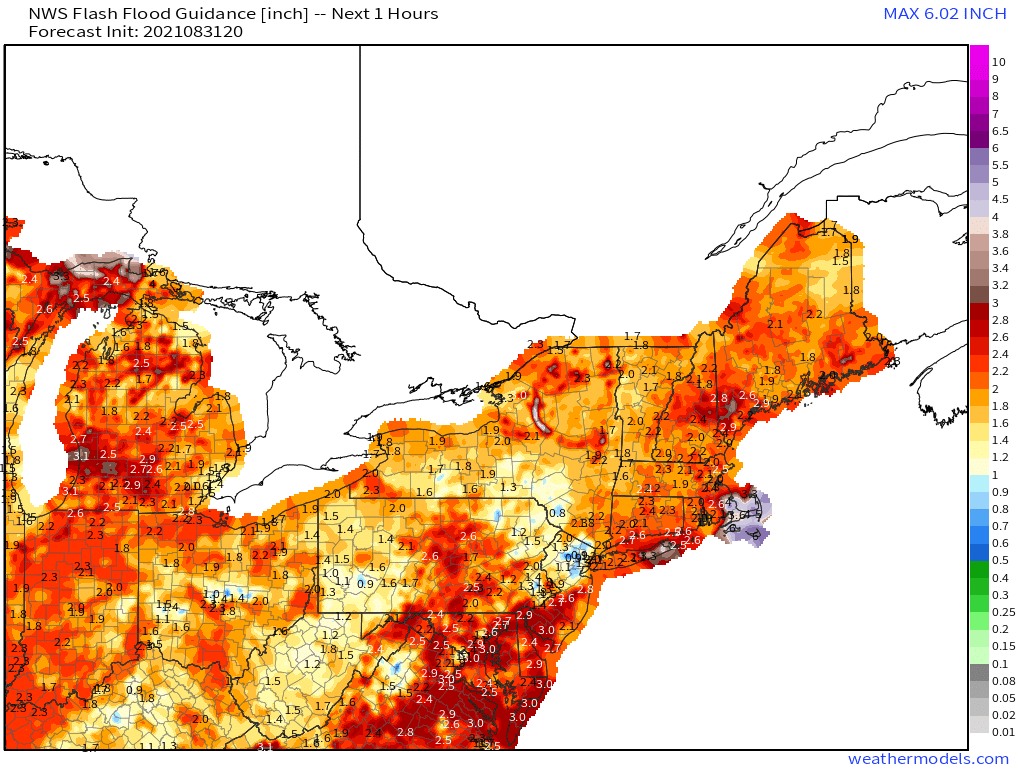

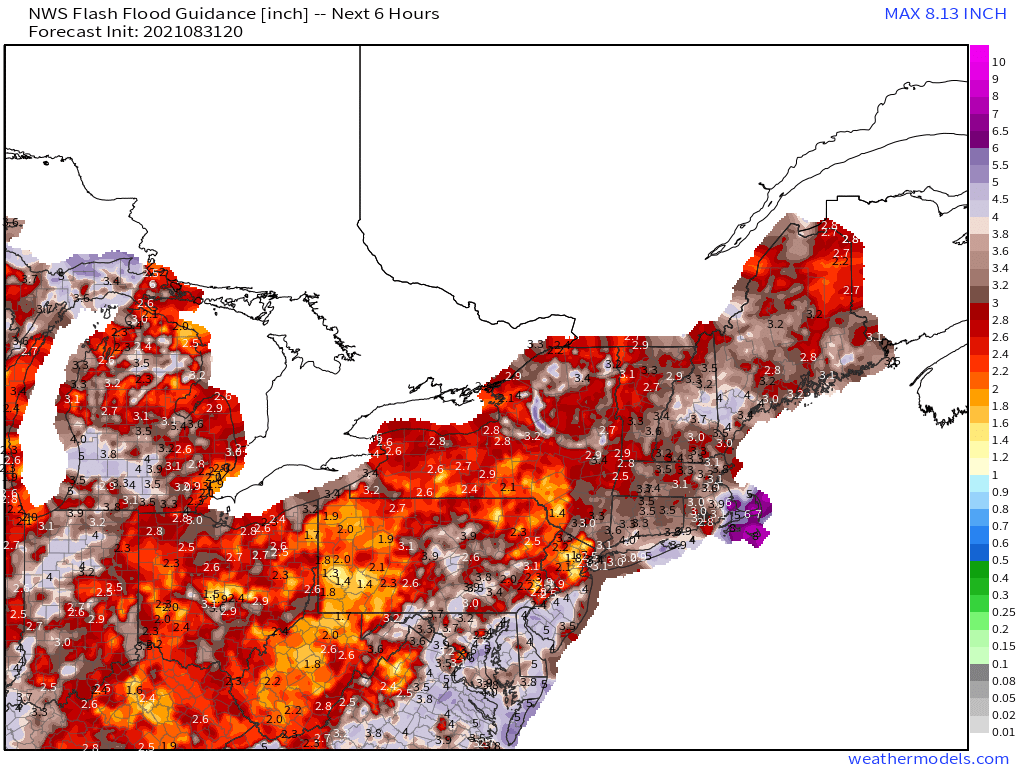

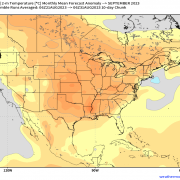

A metric of the ability soils have to support rainfall is known as flash flood guidance, or FFG. The index measures the amount of rain that must fall in a specific time interval to cause flash flooding, and a look at FFG over the northeast shows how two weeks of very heavy rain have substantially gnawed away at the buffer in places.

You can find two different versions of the FFG map above- the first for one hour of rain, and the second for six hours of rain. For parts of the Northeast, specifically West Virginia, southwest Pennsylvania, northeast Pennsylvania, southeast New York, and northern New Jersey, both maps show values that are extremely depressed.

The stage, if you will, is set. Very well, mind you.

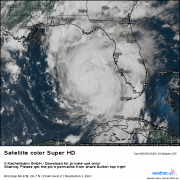

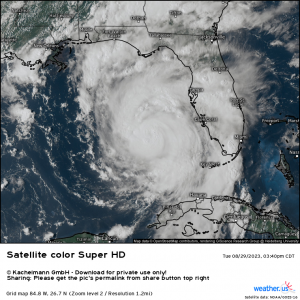

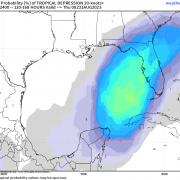

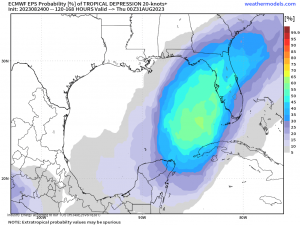

Ida, meanwhile, is sliding slowly north in the vicinity of the southern Appalachians today. The storm appears fairly disorganized, but carries a very potent envelope of tropical moisture released into the atmosphere around Ida by the same processes that helped it strengthen over the Gulf.

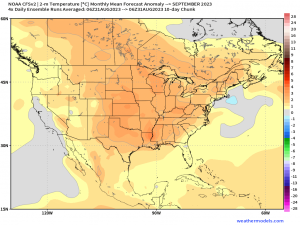

This excessive moisture can be seen in the field of modeled precipitable water, a metric of how much atmospheric water is present in a given column. Amounts that exceed 2″ are quite uncommon in the Northeast, and represent extreme moisture for the area.

Ida’s remnants bring more to the table than just extreme moisture content, however. They also provide deep cloud warmth capable of generating very efficient rain, southerly flow that can continuously inject moisture into storms, and atmospheric energy (CAPE) supportive of the type of convection that generates substantial short-term precipitation rates.

Notice, in the precipitable water loop above, an additional feature aside from Ida’s moist envelope- very dry air surging south near the Canada/US border. This is associated with the cold front that will stall over the Northeast tomorrow, a representation of the baroclinic processes that will clash with the tropical cyclone to produce prolific rainfall.

Tropical cyclones are better than extratropical storms at almost everything related to excessive precipitation. However, the asymmetries inherent in the latter can outperform the former in developing compact, intense zones of midlevel lift. This is clear in the definition of a non-tropical cyclone: a pressure depression with fronts.

As Ida is increasingly swept along an extratropical boundary tomorrow, it will have the best of both worlds, carrying the aforementioned atmospheric parameters very supportive of heavy rain alongside the intense, large-scale lift provided by non-tropical fronts aloft.

This ‘front’ can be seen where strong southerly flow smashes into weaker easterly flow in this model loop. The result of such convergence is vigorous lifting of moisture into rain.

Notice, also, how the low seems to zipper along the zone of convergence tomorrow. This sort of parallel enhances the odds that very heavy precipitation will train along the same places, bringing a mixture of deep tropical stratiform and low-topped convection capable of extreme rainfall rates.

The training of intense lift amidst a deeply tropical atmosphere from Ida’s remnants will lead to extreme rain- if you will, the actors and actresses of the show flawlessly performing.

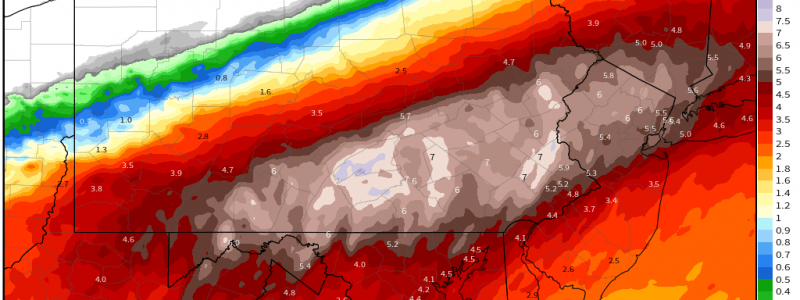

Convective allowing models, as a result, depict rainfall totals that are nothing short of breathtaking. Remember, predicting convection is hard, so the most important conclusion should be the amount that falls in the maxima, not the location of these maxima.

If these actors performed in a decrepit alleyway, they’d attract a crowd. But they aren’t- remember, they have a stage set historically well. Opening night isn’t until tomorrow, but critics suggest this could be a play to remember.

Substantial rain will fall atop soils that won’t be able to absorb it across a swath of the Northeast. Flash flooding will be widespread and severe tomorrow as a result, especially in a zone from northwest West Virginia to near Scranton, towards the lower Hudson Valley and into southern Connecticut. River flooding will also be quite likely in these areas, as all that runoff eventually flows downstream.

This could well be the worst flash flood event since Irene and Lee brought the interior northeast to its knees in 2011. Remember, folks- turn around, don’t drown.