Early Season Wildfires Spark Concern Out West

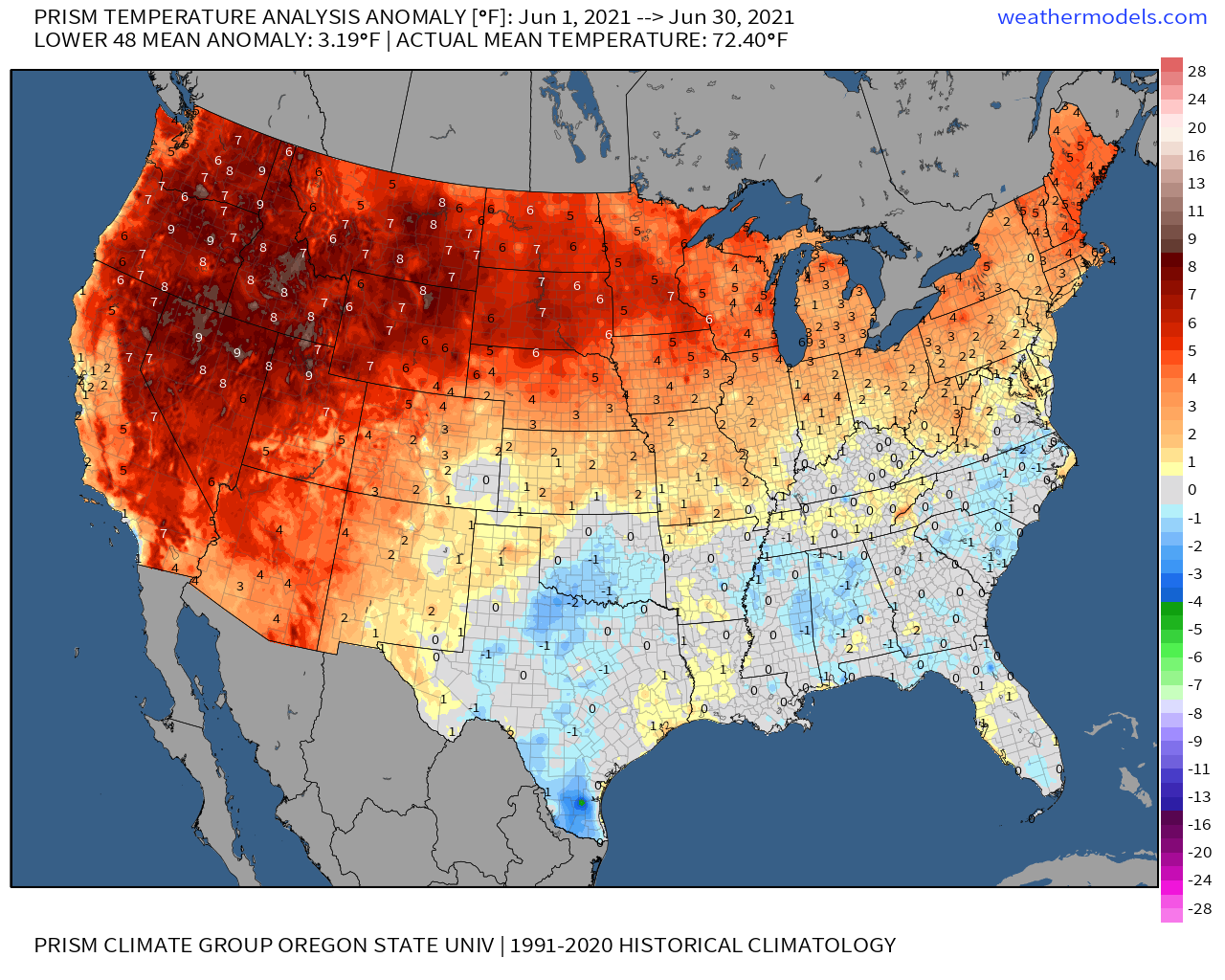

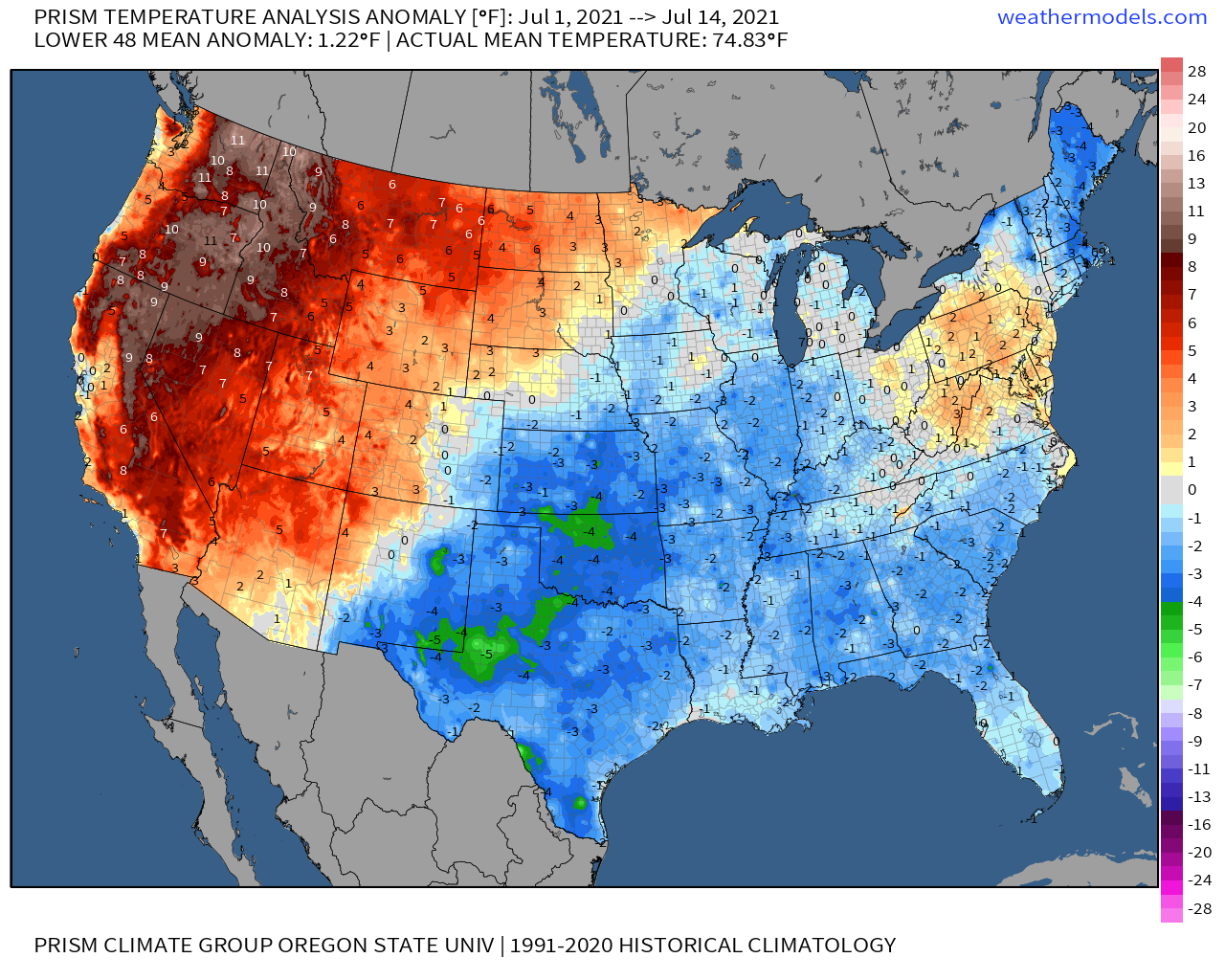

When I wrote about the West’s mega-drought last month, a dire two year dry spell imbedded within a dry two decades had sent much of the West lurching towards exceptional drought delineation. I expected the vanishingly low associated soil moistures to encourage extreme heat, drying the ground further and deepening drought, as the summer wore on. Unfortunately, extremely anomalous heat events in the Southwest and Northwest validated these concerns, with June and July both exhibiting unusually widespread and intense positive heat anomalies in these places per PRISM reanalysis.

Another concern I wrote about back then was fire danger, which increases dramatically as fuels dry in hot drought.

Ironically, the sometimes drought-quenching monsoon can bring a mid-summer escalation of this risk with a moisture influx that sometimes promotes lightning, which can ignite wildfires when accompanying storms are insufficiently rainy. In the dry, high-LCL environment that is the West, rain sometimes evaporates before it hits the ground, which can further enhance such a risk.

Even sans monsoon-inspired sparking, conflagrations can ignite whenever sufficiently dry fuels come into contact with arsonists, power lines, gender reveal parties… or fireworks. The last is why the Fourth of July often sees by far the most human-ignited fires of any day of the year.

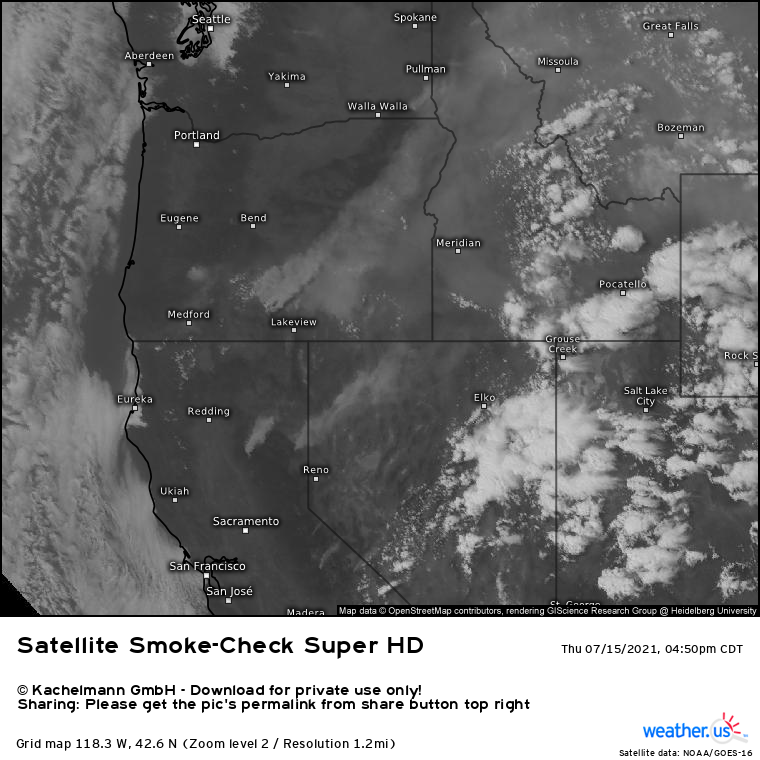

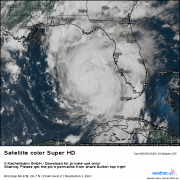

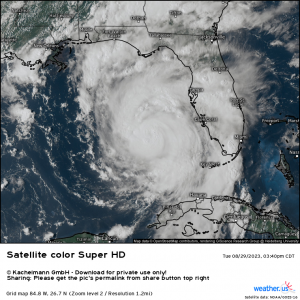

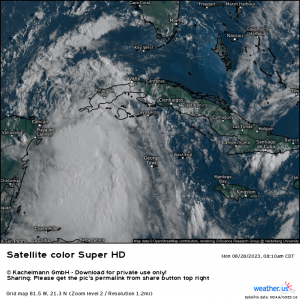

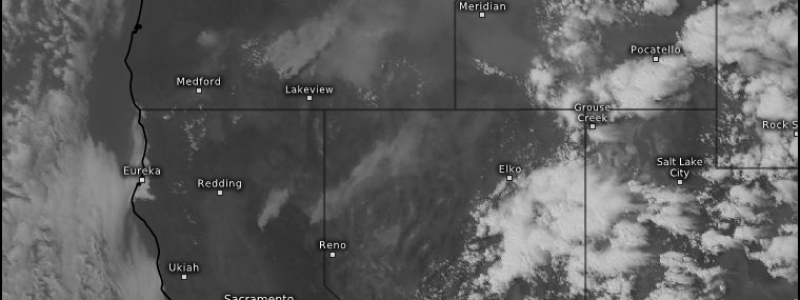

So, with dry fuel aplenty and some typical July ignition sources mixing in, it’s no surprise that this year’s wildfire season is roaring to life anomalously early. A number of intense wildfires have been noted, particularly across the Northwest, which saw a lot of fuel ‘flash dried’ by the incredible heat event there. These fires can be seen indirectly by using satellite imagery to locate smoke, which indicates both the existence and size of wildfires. Take a look:

A glance probably reveals a huge collection of smoke over SE Oregon. If this is the first thing you noticed, congrats: it’s probably the biggest fire threat currently over the West. Called the Bootleg Fire, it’s already burned 144,000 acres and is still growing. To put that number in perspective, this pre-peak-season fire has already consumed more acreage than all Oregon fires of the 2019 season combined.

Why, exactly, do we consider July “not peak season” if fuels are vanishingly dry and ignition sources are aplenty? The main reason, besides the further drying of plant matter that happens through fall, is the large lack of kinematic support. Brisk winds that serve to oxygenate and propagate fires are largely scant this time of year, as the midlevel jet contortions that support cranking offshore flow typically wait until approximately September to descend from the poles. This seasonal unfavorability makes fires like the Bootleg even more unusual and ominous, as it begs the question: if a single fire in July can burn more of Oregon’s forests than the entire 2019 season, what does the rest of this dry, dry season hold in store?

But I digress. A look south, across the forested sub-Sierra spine that arcs east of Redding and Sacramento but west of Reno, shows that numerous smaller fires are also sending fingers of dense smoke east with the jet stream. In California, 142,477 acres have already burned, which is less than an order of magnitude below a typical California season. Not great for July!

The news isn’t all acutely bad. Barring some widespread wind or ignition event, it seems unlikely wildfires currently active or still to come will explode into the type of calamitous burns we grew used to last summer for at least another couple months.

Some of the news is acutely bad, however. Intermountain ridging out West will actually leave the coast vulnerable to subtle troughing amidst the typical northeast Pacific summertime high.

If it were January, we could be talking drough-busting atmospheric rivers, but the unfortunate result will instead be the potential for subtle moisture infusions from the southeast.

Models project one of these for the weekend. Unfortunately, atmospheric moisture amidst the very dry mid-July air only means an increase in dry lightning potential, which is what caused the worst firestorm in modern Californian history last August. While nothing nearly as bad is likely, a repeat of those rolling thunderstorms to even a degree amidst similarly (or, in places, more-so) bone dry fuel could be very destructive. It’s still only a possibility, but it is one that bears watching.