An Astonishing Record, a Devastating Flood

On Saturday, as much of the nation’s attention was turned towards hurricane Henri off the east coast, a substantial rain event in Tennessee left 22 dead and dozens missing. Sometimes it can feel as if I have my finger on the atmosphere’s pulse, yet other times I am blindsided by violence from above- this was one of those times.

This retrospective will uncover how the atmosphere was capable of contorting itself into such an extreme, devastating state for hours that day.

Rain requires lift and moisture. Thunderstorm rain requires one more ingredient: convective instability. The more plentiful this moisture is, and the more robust the instability, the heavier the rain can be. If these two ingredients exist in large enough quantities, and coincide for a long enough time with lift, rain can exceed the environmental capacity to whisk water away via soil absorption, streamflow, and manmade drainage.

This is the story behind every rain-induced flash flood event that ever has happened and ever will happen. Instability, lift, and moisture coincides in excessive amounts for an excessive amount of time, exceeding the ability of the environmental system to safely remove it.

Moisture, of all things relevant for flash flooding, is hardest to come by in great excess. Evaporated from oceans, lakes, and gulfs, atmospheric moisture must move over land to produce heavy rain, which can only happen if air moving from place to place pulls it along for the ride. But more than just marine-source advection is required: for really profuse, truly excessive rainfall to occur, atmospheric moisture typically has to ‘pool’ for a long duration, either within a tropical storm or within a particularly stuck-up southerly flow regime.

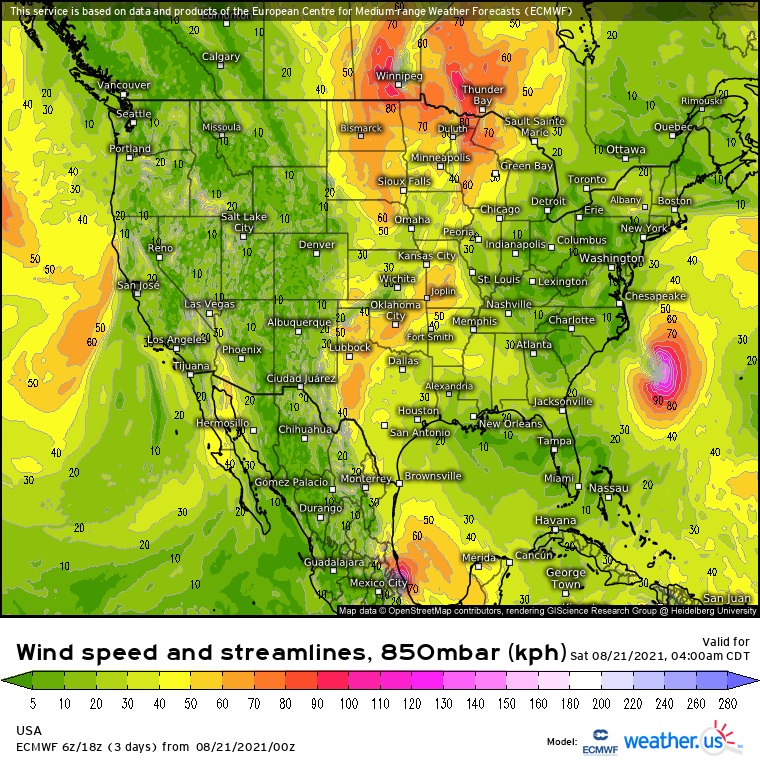

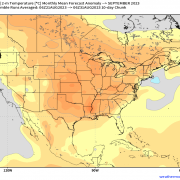

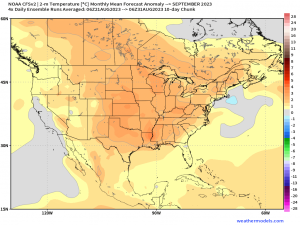

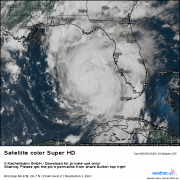

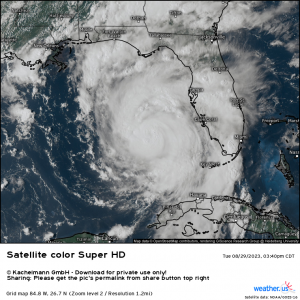

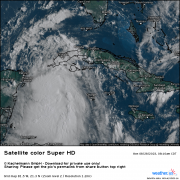

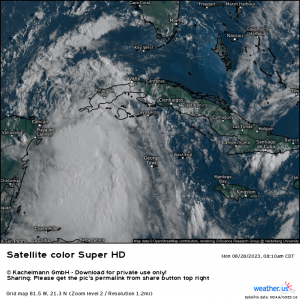

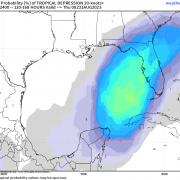

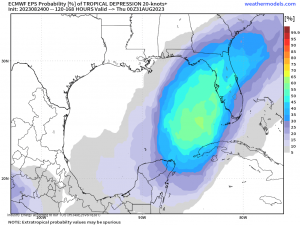

The atmosphere that enveloped western Tennessee by Friday night developed slowly over the southeast as a combination of Gulf evaporation, moisture blowoff from Fred, Henri, and Grace, and evapotranspiration sat idle beneath a ridge. Moisture steadily deepened in this environment and slowly inched northeast until, by very early Saturday, precipitable water to 2.5″ enveloped west Tennessee.

Deep moisture, like what was present over Tennessee that night, is not just useful as ammunition for a flash flooding rainstorm. It also holds an incredible deal of ‘latent heat’ energy, waiting to be released upon condensation. This is the basis behind convective potential energy, and the atmosphere over the area was chock full of it.

By the early hours of Saturday, west-central Tennessee was under a regime in which air lifted by convergence could blossom into fairly vigorous convection, tap into substantial moisture, and drop prolific rainfall. Of course, that lifting mechanism was still needed.

It would develop as a midlevel warm front struggled to pull itself northeast amidst weak synoptic scale forcing. As it reached middle Tennessee, it actually began to clash with northerly flow responding to the Henri/trough system that was enveloping the east coast. the result was an effectively stalled front aloft, coinciding with plentiful instability and drowning in moisture. The setup, suddenly, was nearly ideal for very heavy rain.

But the lifting mechanism can’t simply not move. Rather, it must not move from the perspective of storms– this that, for an effectively immobile warm front oriented to the ESE, midlevel flow must steer storms to move towards the ESE. That way, to a location along the stalled front, it is as if being hit by the cars of a train moving along static tracks: over, and over, and over. Through this ‘training’, profuse rainfall could last for a long enough time to cause substantial flash flooding.

This brings us to convective initiation just after midnight on Saturday, 8/21. Amidst modest nocturnal instability and diffuse forcing, initial storm along the elevated front brought perhaps a half inch of rain to a region between Jackson and Nashville through 1:30am CDT. Slowly, though, updrafts found ways to deepen, and rainfall rates began to exceed 1″/hr by 2am.

Convection tracked slowly amidst weak August flow, and it tracked parallel to the front that initiated it. As the front stayed still, the heavy thunderstorms trained.

By this time, thunderstorms over SW Kentucky had rainfall rates exceeding 2″/hr, indicating a deluge capable of causing flash flooding in poor drainage areas. Some limited flooding began to commence near the west Kentucky/Tennessee border as the deepening convection amidst excessive atmospheric moisture began to exceed the capacity of soil to retain moisture.

But these storms still were forced to move along the same tracks as the ones before, trouble for locations downstream. By 3am, flash flood guidance was exceeded SW of Dickson, Tennessee, with more rain backbuilding upstream. And still, the train of excessive rain barreled down the immobile tracks of the elevated boundary.

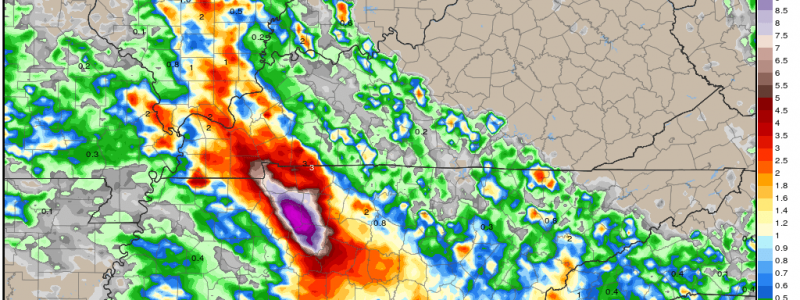

By 4am, almost the entire band of showers along the warm front involved convection with rainfall rates to an astonishing 3 inches/hr. Flash flooding was well underway southwest of Dickson, where a large swath of three hour rain totals approached 6″, exceeding the 200 year return interval. Flash flood guidance was exceeded by 200%, indicating critical runoff. Unit flow locally exceeded 10m³/km², a rate only seen in ‘considerable’ flooding that presents a real danger to life and property. At this point in the event, the rain could have stopped, and the flooding would have been memorable and dangerous.

But it didn’t stop at 4 am. Instead, thunderstorms just as capable of producing prolific rainfall built upstream, ready to pounce.

The next three hours, through 7 am on Saturday, 8/21/21, will indubitably go down in hydrological history. The front didn’t move, and neither did midlevel flow, blowing punch after punch of a monumental deluge straight through west-central Tennessee.

The part of the state that had just seen 4-5 inches of rain in three hours saw an unbelievable 8-9 more by 7am CDT. Six hour rain totals approached 13″, and a huge swath of 200 year six hour flooding extended from just SE of Murray, KY to just NW of Columbia, TN. Flash flood guidance was exceeded by over 400% in places, with catastrophic runoff occurring across multiple towns. By now, unit flow well exceeded 20m³/km², a flash flood emergency of astonishing proportions. And still, rain lined up for miles upstream along a front that just would not move.

The next three hours were similarly calamitous for parts of west central Tennessee. While the heaviest of the rain had fallen by 7am, extremely prolific rain continued to fall along the same narrow swath of the state, effectively all converting into a deluge of runoff that swamped roads, neighborhoods, and streams.

By 10am CDT, another 7-8 inches of rain had fallen along basically the same swath. 12 hour totals now approached 17″, a calamitous amount of rainfall. The massive swath of recurrence intervals between 200 and 1000 years expanded ever wider, with six hour flash flood guidance values exceeded by more than three thousand percent. Unit streamflow predictably increased once more, with values reaching 30m³/km² at times. Remember, 10m³/km² of unit streamflow is often associated with ‘considerable’ flash flooding.

As rain at last tapered off by noon, a phenomenal scar of flooding had been stricken across the state, with local totals exceeding 17″.

This amount of rain almost certainly set the daily statewide record by an incredible 3″, an especially astonishing statistic considering the lack of clear topographical or direct tropical influence on the event.

22 people were tragically killed in this horrific event, with dozens still missing and hundreds of structures severely damaged or destroyed. It serves as a reminder of the necessity of time in forecasting weather, a fourth dimension that can turn ordinary events into catastrophic disasters.