Guidelines For Determining Winter Precip Types

With the start of Meteorological Winter and the possibility of a favorable pattern for wintry weather in the Eastern US looming in the mid-range, it’s time once again to review winter precipitation types and the soundings associated with them.

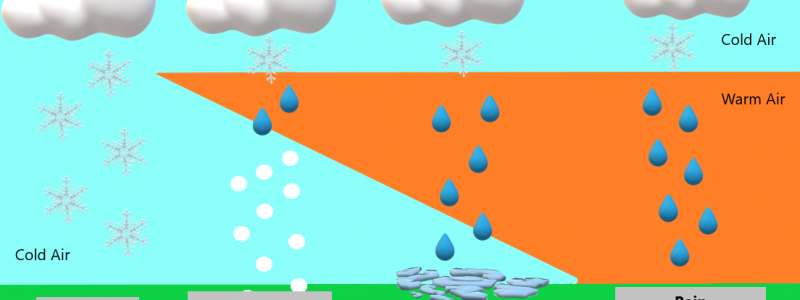

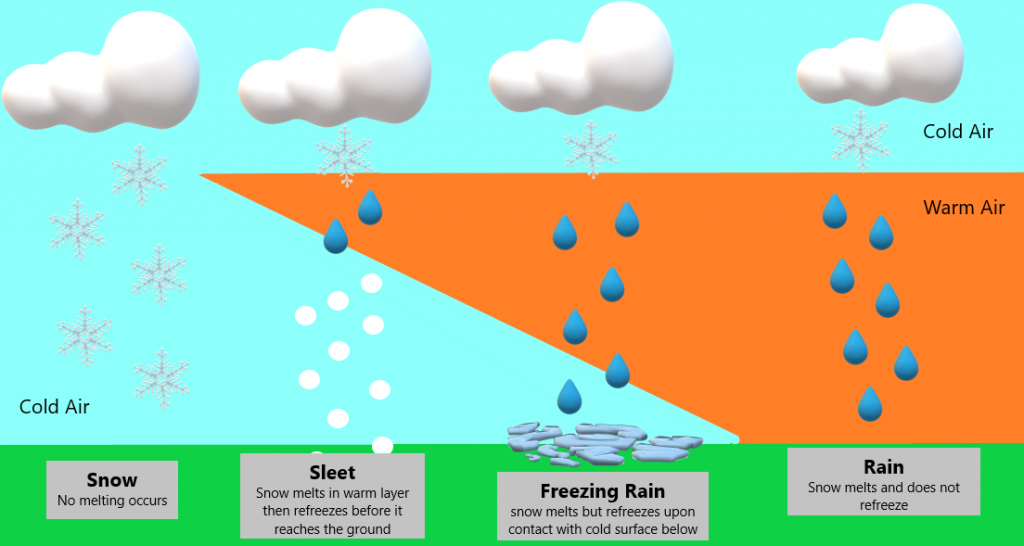

I’m resurrecting this graphic from roughly two years ago for a quick visual. These are the basics of what leads to a specific precip type. As with many things in meteorology, it can be a bit more complicated than displayed above – which is why I’ll go into detail below. Let’s look at a few soundings to understand better.

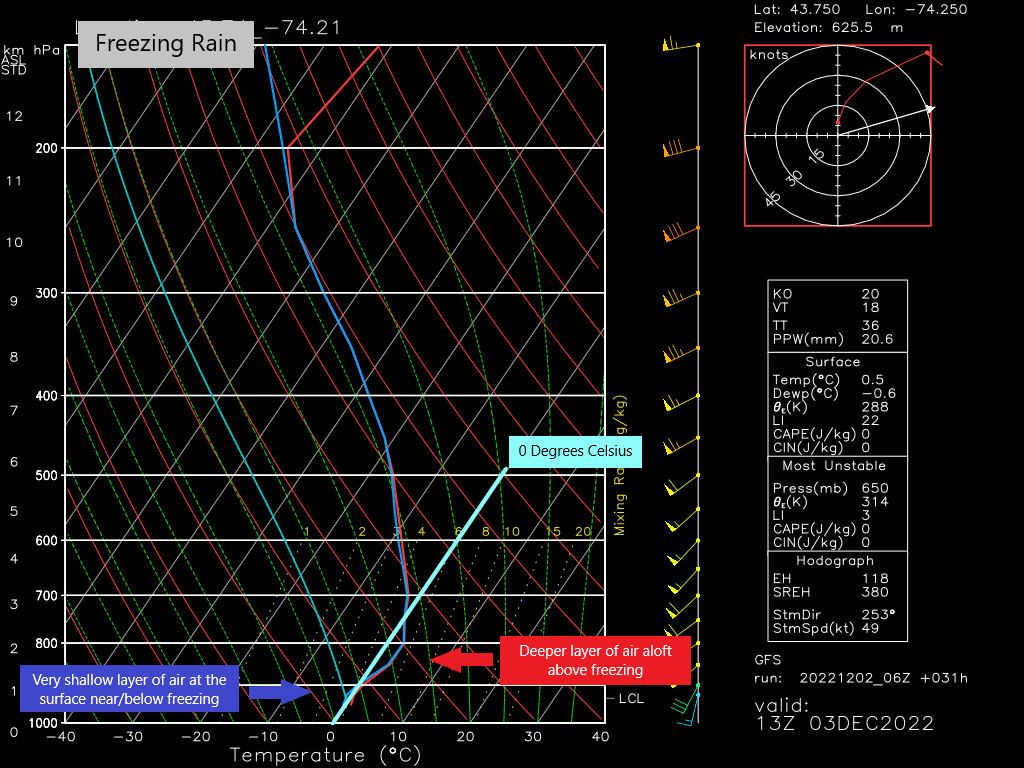

Freezing Rain

Freezing Rain is the black sheep of precip types. It’s raining when it’s cold enough to snow, and then, adding insult to injury, it freezes on the roads and trees causing horrendous driving conditions and power outages.

Since it has the possibility to be highly impactful, it’s important to spot conditions that may result in freezing rain.

- A thicker layer of warm air in the mid to low levels

- A very thin layer of air near/at/below freezing at the surface

These are the usual conditions in which freezing rain is seen, but there is one more that is a bit on the sneaky side and can result in freezing rain when the entire column is sub-freezing:

In order for snow to form, we need to be saturated in the snow growth zone. This is the region of the atmosphere that is roughly between -10 degrees C and -20 degrees C. If this region is dry, but the layer below is saturated, precip will be rain, regardless of the temperature. Without ice crystals to condense on, snow will not form. Instead, rain will fall and then freeze once it hits the surface.

Like I said, sneaky. Saturation in the snow growth region is a very important factor when predicting winter weather and should be the first ingredient a forecaster checks.

Sleet

The pinging of sleet on my roof was a sound I hated as a child. School would cancel for snow, but definitely not for sleet. It’s a decision that’s understandable since sleet, unless it falls in large quantities, isn’t quite as dangerous as freezing rain or heavy snow when it comes to travel.

In order for sleet to fall we need:

- A saturated snow growth zone (DGZ)

- A shallow layer of air above freezing aloft

- A deeper layer of sub-freezing air in the low levels/at the surface

Sleet occurs when snow falls into air that is above freezing, melts partially, and then refreezes in the deeper cold layer closer to the ground.

Some guidelines exist for determining whether a layer of warm air will allow for partial melt (sleet) or total melt (freezing rain):

- If the depth of the melting layer is 1500 ft to 4500 ft, it supports some level of melt. Closer to 1500 ft will support a partial melt while closer to 4500 ft will support a total melt.

- The temperature of the melting layer matters. If the layer is just above freezing (1-2 degrees C) a partial melt is likely. If the layer is closer to 4 degrees C or more, a total melt is likely.

You’ll need to consider these factors together. For example: If the depth of the melting layer is only 1600 ft, but the maximum temperature in that layer is 5 degrees C, that’s a total melt.

Conversely, if the depth of the melting layer is 2700 ft, but the maximum temperature is 2 degrees C, a partial melt is likely.

Hopefully that makes sense. Winter precip type forecasting isn’t easy, y’all.

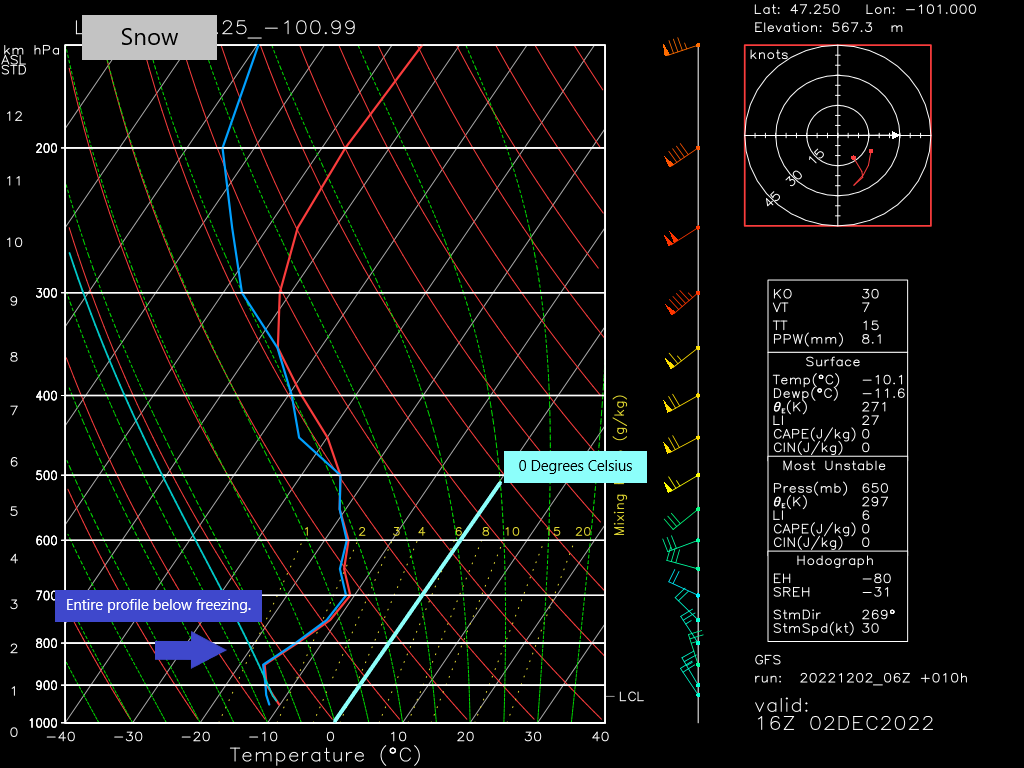

Snow

Snow is the easiest to forecast, right? All you need is a profile completely below freezing and you’re golden.

Not so fast.

- Check your DGZ!! If the region between roughly -10 C and -20 C isn’t saturated, no snow for you!

- Check your wet bulb zero height. This is the height where the temperature will read 0 C once moisture evaporates into drier air. If the temperature at the surface is above freezing but the wet bulb zero height is at or below roughly 1000 ft, you can still see (wet) snow at the surface.

- If a melting layer is present, it can be less than 1500 ft thick or colder than 1 C and snow will likely survive.

Quite a big of analysis goes into winter weather forecasting. Skipping a step can easily mess up your forecast. Some final important tips before I go:

- Use soundings! The vertical temperature profile is VERY important in winter weather forecasting.

- Always, always check the saturation of your DGZ. If there is no moisture in this layer, there is no snow.

- If a melting layer is present: how deep is it? What’s the maximum temperature in this layer? Is it further aloft or closer to the ground? This is important information when determining freezing rain vs. sleet.

- Know the wet bulb zero height. If the surface temperature is slightly above freezing but the wet bulb zero height is below 1000 ft, there’s still a chance for wet snow at the surface.

Hope you learned something new today that you can use in the months ahead! Oh, and if you have any tips that have worked well for you over the years that aren’t listed here, I’d love to hear them. Share them in the comments below!