The Atlantic Tropics — Why the Slumber? Change on the Horizon?

Hello!

A quick introductory about myself: My name is Armando Salvadore, and I’m a meteorologist who has graduated from Mississippi State University this past May. I’m going to be a first-year graduate student at Mississippi State looking to focus my research on long-range forecasting. I thoroughly enjoy blogging about winter weather as you could consider myself a “snow-geek”, but I enjoy all facets of how the atmosphere works and continuously trying to learn how and why!

Tropics:

Despite flipping the calendar to August, the Atlantic hurricane season appears to remain in a slumber, and it’d appear so for at least the first half of the month. You make ask however, why? Before I begin to dive into the reasoning, believe-it-or-not, we’re actually only about 33% of the way into Hurricane Season. From a climatological standpoint, we typically don’t even see the bulk of hurricane activity until after August 1st. The “peak” of the season isn’t even until September 10th, so it’s not unusual to see a lull in July and into August. Now, what’s the prominent reasoning for why we’re seeing such slow, almost non-existent tropical development across the Tropical Atlantic?

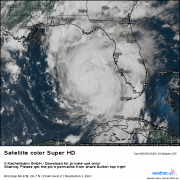

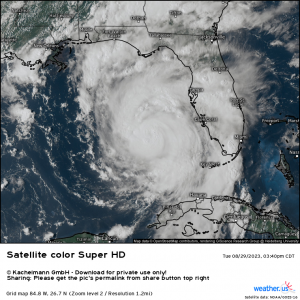

This product displays what essentially is dust, or aerosols in the atmosphere that emanate from Africa. In this loop, you can see plumes of dust, which is coined as the Saharan Air Layer – dry, dusty air that originates from the Saharan Desert. This air, because it’s less dense than the surrounding cooler marine air (warm air wants to rise since it’s less dense!), gets lofted up to the middle levels of the atmosphere where the easterly trade winds then transport this air across the tropical Atlantic. These plumes of Saharan Air travel thousands of miles across the Atlantic and MDR (Main Development Region), which can reach the United States and actually cause poor air quality and hazy skies. Tropical storms need several key ingredients to form, maintain, and intensify is conditions are met:

- Low vertical wind shear (i.e. change of wind speed and/or direction with height). Hurricanes like to be vertically stacked. Wind shear disrupts circulation, and can’t sustain since it cuts off key processes that allow these cyclones to maintain and develop.

- Moist environment! Dry air is the “bane” of tropical cyclone existence. You want to see the low and mid levels of the atmosphere with high relative humidity. Dry air, or Saharan Air, basically cuts off critical meteorological processes whereby instead of latent heat fluxes – key in maintaining convection allowing air parcels to continue to rise – you get this drying effect, leading to stable conditions that inhibit thunderstorm development. We need thunderstorms and convection to allow tropical development maturation.

- A pre-existing “seed”, or disturbance, to set the foundation for a tropical disturbance to eventually grow into a tropical cyclone. We see these emanate off Africa or can manifest from the Inter-tropical convergence zone.

- Warm Sea Surface Temperatures that extend at least ~50m deep that are at least 26.5*C (80*F) to allow for necessary latent heat and important processes in developing convection.

- At least 5* of latitude away from the Equator because the Coriolis force is essentially non-existent, which the Coriolis force is the reason why we see deflection of air (deflects to the right in the Northern Hemisphere; left in the Southern Hemisphere) the further one gets to the poles of the Earth, and we need spin for storms to even exist.

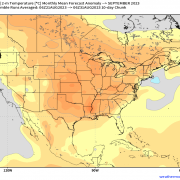

If you have these main ingredients met, the probability of getting a tropical cyclone to form is great! As you can see from above, those plumes of Saharan dust inhibits tropical development, which explains mainly why we’ve not seen much if at all, across the Atlantic. Speaking of vertical wind shear, these dusty plumes also are responsible for eliciting wind shear. Take a look below at the middle-levels of the atmosphere where we like to look to see how strong the wind shear is. Typically, you want to see values less than around 20 knots that are conducive for a favorable environment, but looking at the medium range, this doesn’t appear to be the case as we’ll see relatively strong vertical wind shear across the tropical Atlantic.

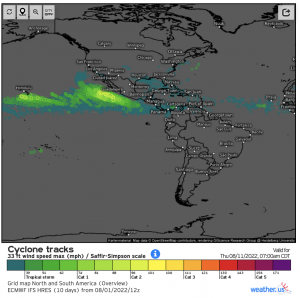

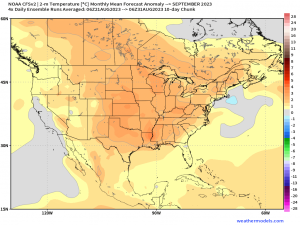

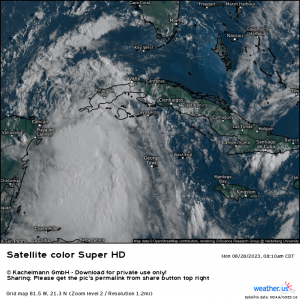

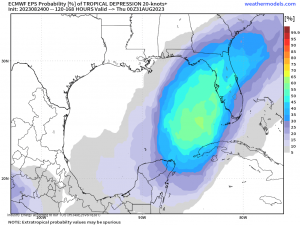

For perspective and to help tether everything together, take a look at both the Eastern Pacific and the Atlantic regarding a 10-day forecast from the ECMWF EPS (European Ensemble). This displays forecasted tracks of potential tropical cyclones. The colors coordinate intensification and if you see clustering, that implies higher confidence that a storm will form and track toward a certain location. As you can see, the Eastern Pacific shows no sign of letting up while the tropical Atlantic remains lackluster for reasons explained above!

So what’s on the horizon; any change or sign of seeing an uptick in Atlantic activity?

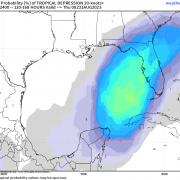

Below is an animated gif of what is called velocity potential, which shows a 5-day anomaly highlighting an average of five days. Allow me to explain and I’ll put this into the simplest of forms; areas of green simply indicate where we have upper-level divergence, or rising air (we look to see where we have rising air because that’s where we have convection). On the contrary, the yellow and orange colors display where there is upper-level convergence, or sinking air (as a refresher, sinking air mitigates and inhibits air from rising – we want rising air for thunderstorms, which eventually allows tropical cyclones to then develop and mature). I’ve outlined to help to show this area of rising air that’s forecasted from the ECMWF EPS that shows this broad area of divergence, or where the ensemble “thinks” we’ll see upper-level divergence. In a nutshell, areas of upper-level divergence (arrows pointing outward from a central point, again indicative of rising motion) and upper-level convergence can be facilitated by atmospheric circulations that propagate along the equator. These systems are what are known as a CCKW’s, or Convectively-Coupled Kelvin Waves. Simply put, these areas of convective “envelopes” help in several ways and are linked to making an environment favorable for tropical development. They can help reduce vertical wind shear, moisten the ambient environment across the Atlantic, and increase “spin” – key critical ingredients that lead to tropical development! See the connection? So it’s these areas that meteorologists and forecasters look to help give a general sense of what could happen at a longer lead-time. It’s not entirely straightforward, as nothing ever is when it comes to the atmosphere, but plenty of research has shown a strong connection between tropical cyclones and these atmospheric circulations. You may have heard of the MJO (Madden-Julian Oscillation), which is basically like a large-scale version of a CCKW and has similar characteristics, except the MJO is much larger as aforementioned and is typically always sought after when it comes to long range forecasting!

In conclusion, and after a rather lengthy blog (I apologize as I tend to get carried away, but explaining in-depth to help convey the message is what I like to prioritize) – here are the main takeaways:

- Hurricane Season in the Atlantic will continue to remain quiet for the foreseeable future.

- The Eastern Pacific will continue to “spit” out tropical disturbances, but fortunately no sign of any hurricane or tropical cyclone to impact any major landmass.

- We’re climatologically only 1/3rd of the way into the season with the “meat” of hurricane activity ahead of us beginning this month!

- Expectations are for tropical development to begin to see an uptick likely within the next 2-3 weeks as environmental conditions become less hostile and more conducive to allow tropical activity.

- Review hurricane preparations if you live along any coastline – whether that’s anywhere in the Lesser Antilles and surrounding areas or from the Gulf coast up toward the Eastern Seaboard – no one should be caught off-guard and have a plan of action!

Hi Armando. Great post. What I wonder is why the experts couldn’t identify in advance the dry & stable air that have put the season in a hold. Right now, seems that the above average season is in doubt, and if August doesn’t produce good ACE numbers, also the average season could be underachieve.

Hi Armondo,

Thanks for writing this however it is misleading to say we are “about 33% of the way into Hurricane Season”. From an activity weighted point of view we are less than 10% in, and even by August 20th we’ll only be about 25% through. Michael Lowry does a good job explaining this in his recent post https://michaelrlowry.substack.com/p/when-does-hurricane-season-typically .

Sincerely,

Craig Setzer