A First Look Into Next Week’s Significant Northeast Snow Threat

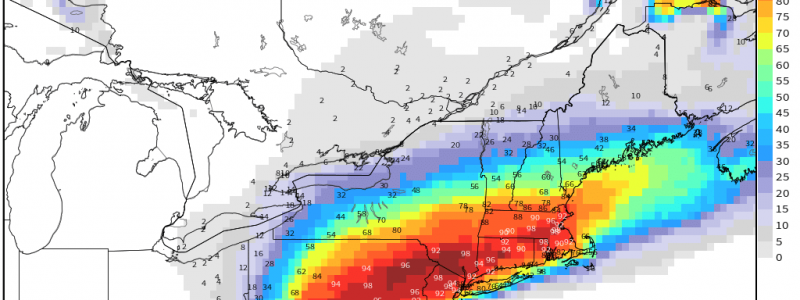

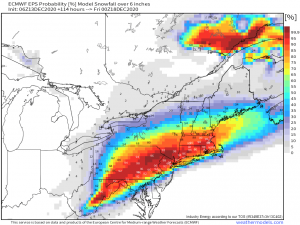

No doubt by now you’ve heard rumors of a nor’easter impacting the east coast by mid-week. You’ve probably also seen snow map after snow map pushing wild totals topping 2 feet in places. But will it happen?

Let me preface this blog with one thing: it’s too early for deterministic accumulation forecasts. There is still some uncertainty involving a few aspects of the storm and a little change could mean a big difference in who sees how much snow. We won’t be posting totals today, but we will be looking at this storm analytically and seeing what we can figure out at this point in time with the information we have.

Remember: the big players are moisture, lift, and cold air. The extent to which the atmosphere allows these three parameters to overlap will determine the strength of our snow.

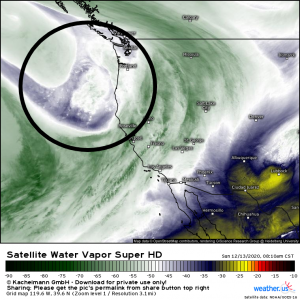

The area of vorticity that will become the much-rumored storm later this week is about to make “landfall” on the Pacific coast. Up until now, it has been over the water which means we have been unable to sample its environment via radiosonde. Once it comes ashore, so to speak, radiosondes will be sent into it and we will know a bit more about this area of energy and, subsequently, the forecast may become a bit more solid.

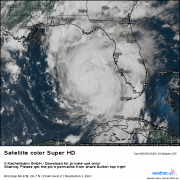

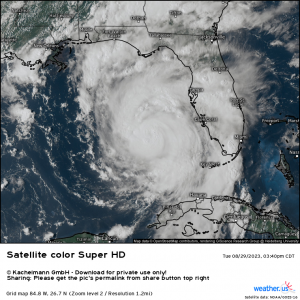

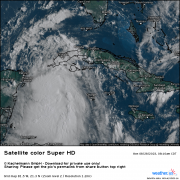

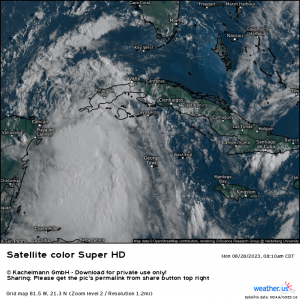

Weathermodels link Weather.us link

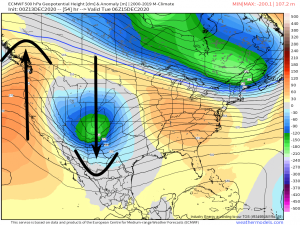

The first thing that needs to happen for this storm to reach fruition is that we need a strong ridge to build behind the area of vorticity. A stronger ridge will allow the trough to dig deeper (what goes up must come down), ultimately placing the storm further south, allowing intensification, and allowing more cold air to filter in ahead of time.

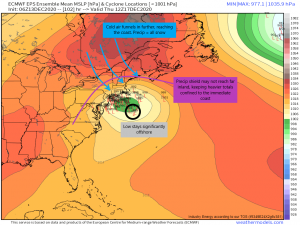

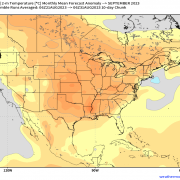

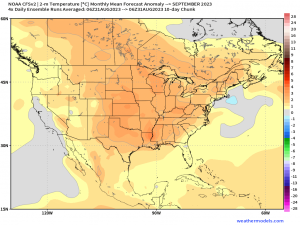

Speaking of cold air, a very strong high is expected to build over eastern Canada. Its clockwise circulation will help to funnel the arctic air needed into the northeast. The high will also get an assist from a very deep 50/50 low (thus named due to the latitude/longitude at which it forms). Its counterclockwise circulation will funnel even colder air toward the high which then brings it down into the northeast along with the air it is pulling out of the arctic.

In addition to cold air, this 50/50 low will allow for a kind of blocking regime to develop over the NW Atlantic. This will force the trough to “buckle” in a way favorable for intense surface cyclogenesis as it moves to the northeast, and it will also prevent the storm from progressing out to sea very fast.

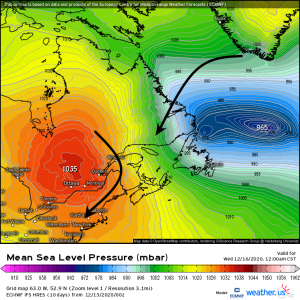

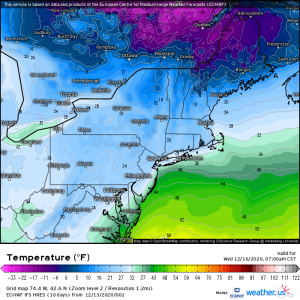

So, with this set up, by Wednesday morning it is plenty cold enough in the northeast for snow.

Naturally, the big uncertainty is the ultimate track of our cyclone.

This may seem self-explanatory, but why does it even matter where our storm ends up?

Well, low pressure systems in northeastern winters are good at transporting moisture advection and cold air advection within a zone that also features intense dynamic lift (from winds slowing and turning in the midlevels). This happens most efficiently and favorably to the northwest of a surface low. Too far S or E, the air isn’t cold enough for snow; too far N or W, the air isn’t moist enough for snow. And in both cases, lift isn’t typically maximized.

So, let’s track the dang thing.

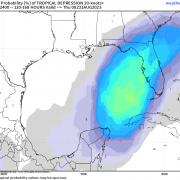

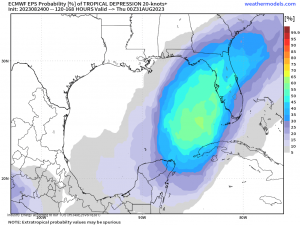

It’s best to use ensembles at this point since, as you can see, there is some, but not complete, agreement between models and different runs. Ultimate track could really make or break this storm.

If the low tracks off shore, it will allow the cold air to filter further south. With the warm sector of the storm off shore and away from the coast, temperatures will be cold all over. This would be a mostly, if not all, snow event for New England. However, depending on the size of the precipitation shield, this could limit the accumulations for inland locations. A smaller precipitation shield could mean next to nothing for places like western New York or northern New Hampshire/Vermont, and lower amounts in places like CT and central MA.

Should the low end up hugging the coast, the cold air won’t be able to filter south far enough to guarantee snow for the immediate coastal areas. In fact, the southerly flow in the warm sector could end up modifying the air enough that this event would be almost entirely rain for those locations. Heavy accumulations would be found inland where the temperatures are adequately cold.

Weathermodels link weather.us link

Judging from the probabilities map, it seems to favor a middle ground solution. The low would track offshore but still close enough to keep totals down on the immediate coast. The heavier accumulation sets up just inland with lesser totals the further west you go.

But let’s step away from the models for a second. Which solution is the most likely?

To start, let’s look back at the 500mb height fields over the W. Atlantic for Tuesday-Friday. There’s a lot going on: notice the giant 50/50 low south of Greenland, the shortwave trough rounding the Appalachians that will bring the northeast snow, and the roaring band of westerlies between the two features.

At a certain point, the motion of the shortwave almost entirely loses its southerly component, and instead rockets to the east. This will likely correspond pretty directly with the termination of the surface low’s track north, which makes it pretty important to figure out why the shortwave begins to move to the east. It appears to me that the increasingly flat westerlies are behind the motion shift, as subtle ridging builds to the northeast of the shortwave and the 50/50 low completely stacks, causing the jet to its south to lose any amplitude. Because the subtle ridging is likely tied to confluence behind the big closed low, it seems that this feature will be the big maker or breaker of the low’s ability to move north, which has crucial downstream impacts on where maximum lift, moisture, and cold air find themselves, and where the heaviest snow falls.

The relative speed at which the big closed low stacks, pumps the Great Lakes ridge, and flattens the jet over the central Atlantic, turning the shortwave to the right, will be determined to a large extent by the speed of the phase with Monday’s system and the Canadian longwave. The earlier the phase, the faster the low will mature, and the faster the shortwave will be kicked out to sea.

I’m expecting Monday’s storm to end up reasonably intense, with a more complete partial phase than some models show right now. This would create rush hour headaches for many, like we talked about in yesterday’s blog. But it would also allow the 50/50 low to strengthen a little more quickly than expected, potentially ushering Wednesday’s storm out into the Atlantic with a more southerly track. This would put the heaviest snow over parts of north-interior mid-Atlantic and SE New England, potentially sparing interior SW New England the most impressive accumulations.

We’ll be tracking this storm in blogs and on twitter, of course!

This blog has been co-authored by Meghan and Jacob.

Great analysis as always!